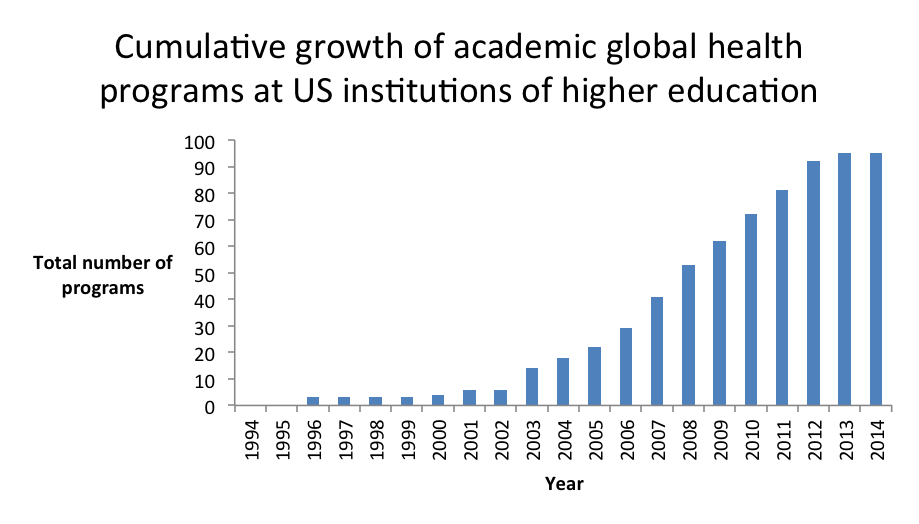

A couple of years ago, some student volunteers and I embarked on a mini-research project to better understand the magnitude and time dynamics of the growth of university-based global health programs across the U.S. You can find our posts and summary of our amateur findings here.

Personally, I’ve seen the remarkable growth and expansion of undergraduate-focused global health educational programs (new majors, minors, centers of interdisciplinary study, study abroad programs, etc) through my work with both GlobeMed and PIH Engage, and seeing the rapid expansion of the Global Health Corps and similar fellowship organizations over the past ten years. In fact, GlobeMed students and many others have been a catalyzing force urging administrators to develop new courses and programs of study.

Our attempt to measure the growth of undergraduate-focused global health program growth at U.S. universities.

Others have also commented and tried to characterize the fairly rapid and significant expansion of undergraduate-focused university-based global health training and educational programs. The Center for Strategic and International Studies has two solid reports, one from 2009 and another from 2014. A flurry of papers have also worked to characterize and have tried to understand the implications of this new focus in higher education. The Consortium of Universities for Global Health has emerged as a powerful force “sharing knowledge and best practices” across universities and colleges, especially between those in “resource rich and resource poor” countries. It seems clear that universities are important and powerful hubs of meaning-making, frame-setting, agenda developing, and training of powerful (or soon-to-be) actors in global health. The magnitude of U.S. universities’ role has grown significantly over the last decade and seems to be growing.

Despite all of this however, I have struggled to understand the drivers of these changes at the university level. Why are these programs being set up? Why are they growing in terms of students, faculty, and influence? What catalyzed this emergence and shift? I think that theorizing on and testing answers to those questions is an important step in understanding the “social movement” for the right to health. University-based global health programs are very important in understanding the full picture of the “field of practice” of global health that has emerged, especially since the emergence of the AIDS treatment movement.

Doing some google and database searching led me to the great dissertation and subsequent research of Karl Maton, a professor of sociology at The University of Syndey. Specifically, his dissertation titled, “The Field of Higher Education: A sociology of reproduction, transformation, change and the conditions of emergence for cultural studies” lays out a compelling theoretical construct that I think is very useful to understand the institutional practices of conservation and change within universities. His case is explores the structuring shifts that led to crises and realignments in English universities during the 1960’s that led to the emergence of “cultural studies” as a legitimized discipline.

His theoretical construct uses Pierre Bourdieu’s field, capital, and habitus (as I’ve tried to sketch in application for global health) in combination with Basil Bernstein’s code theory to develop an explanatory mechanism for change and stability within the university, which he sees as an “emergent and irreducible social structure.” The combination of Bourdieu and Bernstein has led Maton to develop “Legitimation Code Theory“. In his study of the changing field of high education in England preceding the development of the new cultural studies discipline is what he describes as a struggle of control over the “legitimation device” — the “languages of legitimation” that dominant actors in the higher education field use to control what is allowed / not allowed. The legitimation device controls:

“the ways in which participants represent themselves and the field in their beliefs and practices are understood as embodying claims for knowledge, status, and resources. These languages of legitimation may be explicit (such as claims made when advocating a position) or tacit (routinised or institutionalised practices). All practices (or ‘position-takings’) thereby embody messages as to what should be considered legitimate. I conceptualise these messages as articulating principles of legitimation which set out ways of conceiving the field and thus propose both rulers for participation within its struggles and criteria by which achievement or success should be measured. The ‘settings’ or modalities of these principles of legitimation are regulated by the legitimation device.” 1

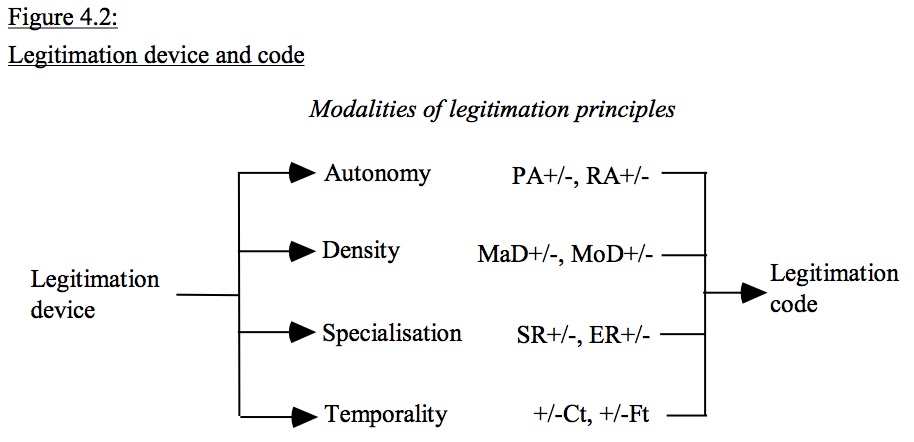

The principles governing the legitimation device are Autonomy (structuring of external relationships to the field), Density (relations within the field), Specialization (relations between the social and symbolic or cultural dimensions of the field), and Temporality (temporal aspects of these relations). Each principle can be ‘set’ (+/-) based on the preference of the dominant in field.

“To analyse change in higher education using these concepts is to view higher education as a dynamic field of possibilities. The legitimation device is the means of generating and distributing what is and is not possible within the field. Positions and position-takings are conceived of as representing possibilities, where some possibilities may be recognised, some realised, but others remain latent (unrecognised and unrealised). A possibility exists within a structured system or field of possibilities; conversely, a field is a structured space of possibilities. The structure of a field (and so the range and distribution of possibilities) is given by its legitimation code modality. Changes in legitimation code thereby represent changes in the structuring of the field and so the space of possibilities. To examine the emergence of new possibilities (such as cultural studies) is to analyse the effects of changes in legitimation code on the field.” 2

The legitimation device defines the dominant and dominated legitimation codes that set up the possible positions and their relative power / authority within the field of practice of higher education.

The legitimation device describes the set of possible positions in field. PA = positional autonomy; RA = relational autonomy MaD = material density; MoD = moral density SR = social relation; ER = epistemic relation C = classification; F = framing; i = internal; e= external; t = temporal +/- = relatively stronger/weaker

Ok, so lots of very abstract theory-talk here. But, I believe that the legitimation device as an analytic tool could be deployed to systematically study the changes in the field of higher education that have occurred over the past 15 to 20 years that led to the emergence of global health as a field of study. What have been the dominant legitimation principles in the most powerful universities in the U.S.? Who within these universities have controlled the legitimation device? Why? What shifts in the broader external political and economic and internal university (student, staff, faculty) environment have exerted pressures on those in control of the legitimation device?

How could those pressures (perhaps those akin to a social movement??) and the competition over the legitimation device create the space for a new domain of global health studies to emerge on college campuses across the U.S.?