Bill McKibbin has a great review of Jane Mayer’s new book, “Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right” in the New York Review of Books. I really want to read the full book, especially since I’ve been thinking more and more about the roots of neoliberalism and the global health equity movement. But, the review is great and I learned a lot from it.

Specifically, I didn’t know the deep familial roots of the Koch brother’s business, political, and economic ideology.

“The origin story of the Koch brothers, however, is like something out of a Robert Ludlum novel, connected to most of the darkest forces of the twentieth century. Their father, Fred Koch, had invented an improved process for refining crude oil into gasoline. The Russians sought his expertise as they set up their own refineries after the Bolshevik Revolution—at first he said he didn’t want to work for Communists, but since they were willing to pay in advance he overcame his scruples and helped Stalin meet his first five-year plan by building fifteen refineries and then advising on a hundred more, across the Soviet Union.”

Next, he turned to another autocrat with busy expansion plans, Adolf Hitler, traveling frequently to Germany where he “provided the engineering plans and began overseeing the construction of a massive oil refinery owned by a company on the Elbe River in Hamburg.” It turned into a crucial part of the Reich’s military might, “one of the few refineries in Germany” that could produce “the high-octane gasoline needed to fuel fighter planes.” And it turned the elder Koch into an admirer of the regime, who as late as 1938 was writing in a letter to a friend that “I am of the opinion that the only sound countries in the world are Germany, Italy, and Japan, simply because they are all working and working hard.” Comparing the scenes he saw in Hamburg to FDR’s New Deal, he said it gave him hope that “perhaps this course of idleness, feeding at the public trough, dependence on government, etc., with which we are afflicted is not permanent and can be overcome.”

Fred met his wife at a polo match in 1932, when his “work for Stalin had put him well on his way to becoming exceedingly wealthy.” They built a Gothic-style stone mansion on the outskirts of Wichita, with stables, a kennel for hunting dogs, and the other paraphernalia required for pretend gentry, and in the first eight years of their marriage they had four sons: Frederick, Charles, and a pair of twins, David and William. The first two were raised by a German governess who “enforced a rigid toilet-training regimen requiring the boys to produce morning bowel movements precisely on schedule or be force-fed castor oil and subjected to enemas.” Luckily for the twins, she left for home when they were born, apparently because “she was so overcome with joy when Hitler invaded France she felt she had to go back to the fatherland in order to join the führer in celebration.”

Of those four sons, Charles became the dominant force, and one of the twins—David—his close colleague. Eventually, by Mayer’s account, they essentially blackmailed the eldest brother, Frederick, out of his share of the family business by threatening to tell their father that he was gay. Bill, too, later parted ways with his brothers, parlaying his share of the inheritance into a lucrative oil business and then using the proceeds to, among other things, fund opposition to wind energy off Cape Cod. But Charles was always the crucial Koch. His father, despite or because of the original source of his fortune, became a fervent anti-Communist and one of the eleven founding members of the John Birch Society. One of the figures in its orbit, Robert LeFevre, became Charles’s original guru, opening a “Freedom School” in Colorado Springs in 1957, where he preached not just the Birchers’ anticommunism but also an adamant opposition to America’s government.”

Thinking back to the piece by Alex Hertel-Fernandez and Theda Skocpol and their analysis of how the Koch brothers’ network of think tanks, grassroots groups, philanthropy networks, etc have formed some kind of a black hole, sucking the Republican party to the radical right, it is easy to see how these efforts have shaped the insane political climate we see today.

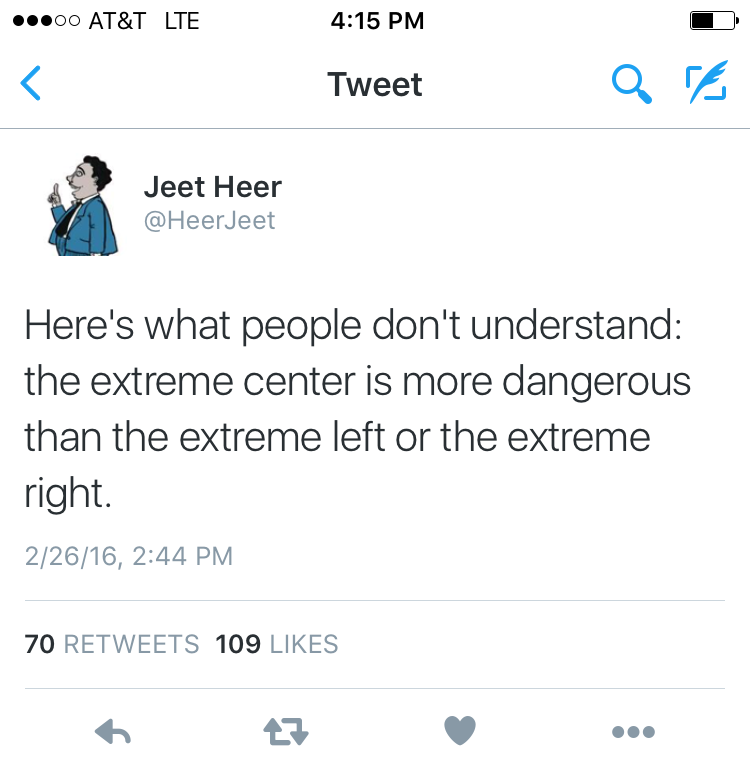

And, now that the Koch brothers are gaining public notoriety (mostly negative), they have started an aggressive “rebranding campaign” targeted at reclaiming the “middle third” of voters who are neither conservative or liberal.

“Perhaps realizing that forty years of heavy spending had failed to make their ideas popular (though often successful nonetheless), the Kochs, Mayer reports, are undergoing a branding makeover, launching a PR campaign designed to appeal to the “middle third” of voters who are neither conservative or liberal. The effort to produce a “positive vision” resulted in, among other things, a “Well-Being Forum” sponsored by the Charles Koch Institute in Washington, where the founder quoted from Martin Luther King Jr. The most substantive part of this image-building has been a drive for criminal justice reform, in partnership with many progressive and minority leaders concerned about mass incarceration who advocate reform of sentencing. But late last fall the coalition began to falter, with many complaining that the Kochs were pushing changes to the criminal code that would make it even harder to prosecute corporate crimes—the very crimes that, as Mayer shows, most of the biggest players in their network have regularly engaged in.”