This past Thursday, we had the third session for CH188: The Right to Health: Problems, Perspectives, and Progress and we focused on 1) readings that laid out the foundational texts that undergird the right to health (the Constitution of the WHO, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Convention on the Rights of the Child, International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, etc.), 2) we heard from guest lecturer Eric Friedman, JD who discussed the current work to more formally codify the right to health through the Framework Convention for Global Health (more here, too), and 3) we began a discussion about the ethical reasoning that underpins all of global health thinking and work and the notion of the right to health. It was a busy session and probably a bit too much to try to cover in a three hour seminar, but we powered through and I think it will provide, once again, a useful foundation as we begin to dive into some of the problems that delay our progress towards the right to health.

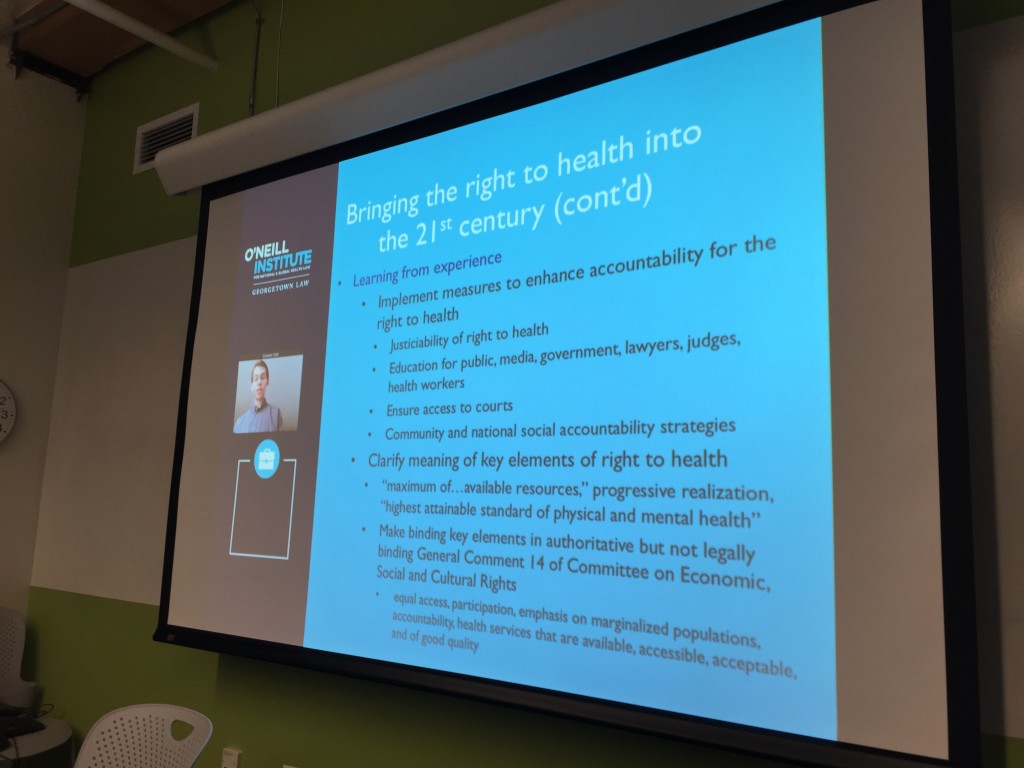

Eric Friedman skyped with CH188 and shared his view of the opportunity for renewed global governance for the right to health.

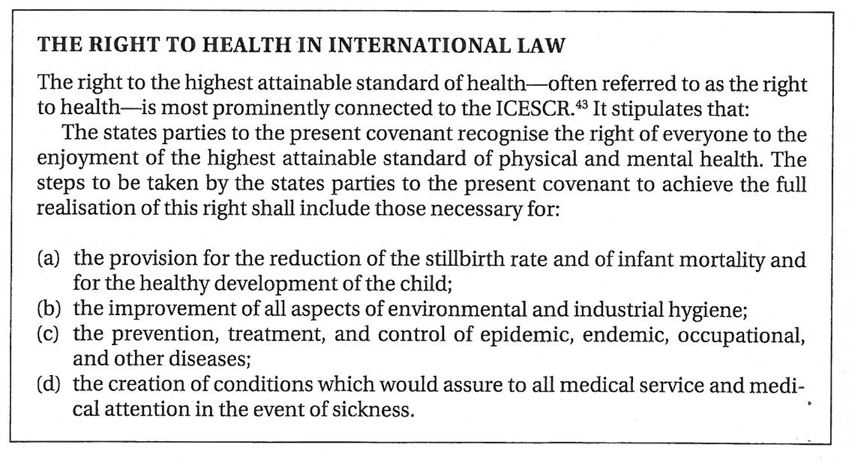

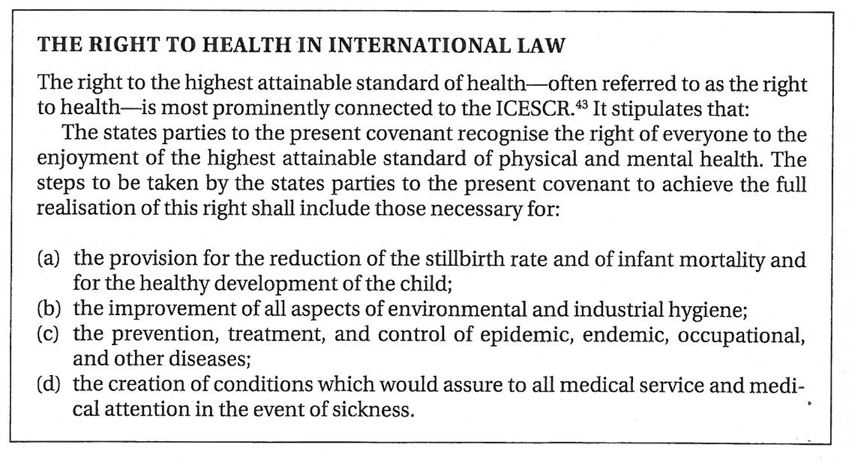

Linking to the last session’s discussion of the history of the global health project, we discussed the historically-rooted documents that to some extent define and provide the structure for arguments and action for the right to health. A couple things stand out to me upon re-reading these documents. First, it’s pretty clear from an international governance that a right to the “highest attainable standard of health” is to be protected across the board. The right to health exists. Second, its important to understand the the historical, cultural, and geopolitical context in which these documents were created. Finally, understanding that history, and the ethical roots of the documents could give us insights for ways to move forward collective work to enable their wider adoption and greater effectiveness.

Summary of the right to health through the lens of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights. 1

What’s lacking is 1) accountability to these goals and mechanisms of holding individual states accountable for violations of protection for the right to health, 2) a commitment to progressive financing mechanisms to help poor countries move forwards progressive realization, and 3) the grassroots movement of people who acknowledge their right to health and who are organized enough to demand that right through their state actors and through broader international action.

I just finished reading Nitsan Chorev’s fantastic analysis of the World Health Organization2 and it’s strategic transformation during two distinct historical periods: the 1970s and 1980s, and the 1990’s and 2000’s. Her analysis, taken with Salmaan Keshavjee’s historical and ethnographic treatment of neoliberalism, construct a useful lens through which to see the changing power of human rights documents and language. Specifically, she looks at how the the WHO adapts strategically to exogenous pressures from states, private actors, and the changing geopolitical / and economic structures.

The 1970s-80s were largely shaped by the political power of the G77 — the block of the poorest countries in the world, many newly independent from their colonizers — and their ability to utilize the one-country, one-vote procedural process within the WHO to exert significant political power towards expansion of primary care and the push (led by Halfdan Mahler) of “health for all by the year 2000.” It was this balance of power within the WHO that allowed the primary care and health for all movements to gain traction and lead to the meeting at Alma Ata. It was during this period that many of the international human rights documents were drafted and when the right to health as an international legal principle gained the most ground.

But, the progressive political block of the G77 during the 1970s and 80s provoked a significant backlash from the wealthiest and most powerful countries in the world, whose action was shaped largely along the lines of the Cold War. As Keshavjee discussed, elite economists in the US and elsewhere were terrified about the potential for a re-emergence of totalitarianism and saw the expansion of Communism and Socialism throughout the G77 as a major threat to liberalism, liberty, and freedom. Hence, the rise of dogmatic neoliberal logic.

The political and financing environment of the 1990s and 00s for the WHO were very different. Understanding that the U.S. and the U.K. could apply other pressure than votes, they began withholding regularly scheduled dues and fees payments to the WHO. They gradually made more and more of the WHO budget focused on discretionary or dedicated budget line items, rather than general expenses. Additionally, the Gates Foundation and other large private philanthropies took a larger role in financing global health including funding the WHO. This precarious and narrow funding meant that the WHO was highly vulnerable to the pressures of states and organizations deeply entrenched in neoliberal logic. The WHO, which had lost stature due to the failure of malaria eradication efforts in the 1960s, had to adapt or grow increasingly marginalized in the global governance of health.

The WHO strategically adapted by transforming neoliberal logic to (to some extent) serve their purposes. Gro Harlem Brundtland, then Secretary-General of the WHO, sought to enlist economists in the effort to demonstrate how targeted, “cost effective” investments made in the health sector could be powerful drivers of economic growth for low and middle income countries. Cost effectiveness became a way of “rationalizing” spending on health services for the poor and created a technical framework by which the WHO could continue to serve as a powerful technical expert to countries around the world, thus staying relevant.

“The prominent role of the World Health Assembly, and therefore of member states, in the process of decision making has secured the dominance of geopolitical logic in the global health agenda. Especially in the first few decades of the WHO’s history, the Cold War division between East and West directly shaped international health priorities (Litsios 1997, Manela 2010). Following decolonization, the World Health Organization, along with the rest of the UN system, was greatly affected by the demands of the newly independent countries of the Global South for a New International Economic Order. In the mid-1980s, in turn, the NIEO logic was replaced with a U.S.-led neoliberal agenda, best expressed in what has become known as the “Washington Consensus” (Williamson 1990). For UN specialized agencies, including the WHO, each period was characterized by the emergence of a distinct global ideational regime and by exogenous pressures to follow that regime. An overview of the policies formulated by the WHO staff and leadership and adopted by the executive and the assembly illustrates, however, that these policies did not faithfully echo the call for a New International Order in the 1970s nor the neoliberal principles of the 1990s.”

- Chorev, Nitsan (2012-05-01). The World Health Organization between North and South (p. 5). Cornell University Press. Kindle Edition.

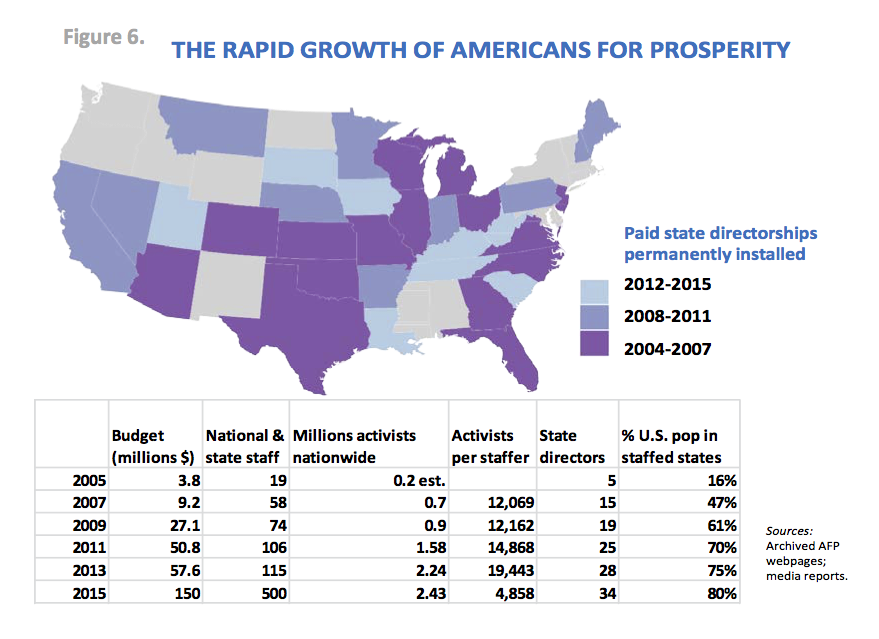

The Framework Convention on Global Health (FCGH) is a modern attempt to once again move the balance of power towards the right to health. Eric Friedman gave a great presentation outlining the growing movement towards a convention, modeled after the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.

See his slides here.

In hist view, the FCGH couple help address key gaps in financing, work to curb the power of non-health sectors, address problems with health worker migration and “brain drain”, and address health disparities within countries. It could accomplish this by leveraging the power of law (powerful norms, facilitation of collective action, and binding responsibilities to support local advocacy), taking advantage of a globalized world in which nation-states should not be sole unit of analysis, and learning from past experience (FCGTC).

There is much, much more to say on the topic of a Framework Convention for Global Health, but suffice it to say, there is stark opposition to such an idea. See the piece from the Health and Human Rights Journal on “the dark side of the FCGH.” I’m hoping to do another post soon diving in to the debate and potential future of global governance in global health.

Reading and Class Notes:

Grodin et al Chapter 2:

- Direct human rights abuses continue: Abu-Ghraib, botched executions, torture, etc.

- Subtle human rights abuses like lack of health systems, discrimination, etc

- Brief history:

- Nuremberg Trials — since then interest in health and human rights have grown.

- Since HIV in the 1980s, health / human rights have had parallel but distinct tracks.

- Jonathan Mann and the HIV treatment movement was the first global effort to link health and human rights explicitly.

- Since the AIDS treatment movement, almost all development agencies and UN programs must acknowledge rights in their health work. Even some governments are building legislation / incorporating into their constitutions.

- Yet, lots of work yet to do and many gaps to be filled.

- WTHO constitution: one of the best sources of “the right to health.”

- The idea of health as a human right as a subject is fairly new.

- Advocacy and bearing witness:

- Complacency of governments in their response to HIV: activists demanded and pushed for action. Result was dramatically reduced cost of HIV medications

- A key dilemma: sustainable action, should it be connected to documentation and denouncements of human rights violations? How would that limit the ability to deliver the services that people need / jeopardize the safety of their workers?

- Rights in Delivery of Care and Programming:

- Examining laws and policies under which programs are being run

- Systematically integrating core human rights principles such as participation

- Focusing on key elements of the right to health.

- Concerns for the future:

- Government roles / responsibilities are increasingly being relegated to non-state actors (NGOs corporations, etc): accountability poorly defined inadequate monitoring.

- Ways forward:

- need to educate staff and engage them in conversations about right to health.

Lecture Notes:

–> Send class information on the TPP.

Consequentialist / Nonconsequentialist Logitcs + Ethics

- Rightness / wrongness based on the consequences / outcomes of actions

- Consequentialist: Utilitarianism is a function of this: action to take is to produce the greatest good for the greatest number. The end is more important than the means.

- Nonconsequentialist: rightness / wrongness are due to the content of the actions. The means matter more than the ends. Actions can be right or wrong. Libertarianism, contractarianism: No policy that causes compensated harm is allowed.

- FCGH: what are the values that are underlying this? What are the values and ethics?

- What constraints will it place on non-state actors?

- What effects will it have on the SDGs? 17 SDGs

- Objective <–> Subjective

- Radical Change <–> Status Quo

- http://www.who.int/hhr/Economic_social_cultural.pdf ↩

- The World Health Organization Between North and South. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. (http://www.amazon.com/World-Health-Organization-between-North/dp/0801450659/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1454782336&sr=8-1&keywords=world+health+organization+between+north+and+south) ↩