My journey to the fight for the right to health stems from a personal health experience: as a three-year-old, I almost lost my left kidney due to infection caused by a congenitally blocked ureter. But, because of the heroic advocacy of my parents, and the resources we had available to us, I was able to receive the reconstructive surgery necessary to repair the damage and save my kidney.

Because my story is the exception, not the norm, I’ve become veritably obsessed with political, social, and economic forces that systematically exclude the vast majority of humanity from access to the care they need to live. Why is it that effective surgical intervention is reserved to the top 1% of humanity? Why is it that I, a privileged white, wealthy, cis-gendered, straight man, am nearly guaranteed a life of comfort and freedom, despite a nearly life-ending congenital illness as a child? Why is it that if I had been born into another body, or in another place, I’d likely not be alive to write these words?

We know the answer: most humans on the planet are deeply constrained by intersectional forces of grinding poverty, racism, sexism, homophobia, and democratic exclusion. Paul Farmer and others have termed this ‘structural violence:’ the violence that seems to have no individual perpetrator–it appears to be all around us, yet not advanced by any of us in particular–that causes the systematic and unnecessary death of the poor, excluded, marginalized, different.

Today, though, we have a name to put to structural violence. It’s called the GOP-led efforts to repeal the ACA and dismantle the only safety-net healthcare program in the U.S. aimed at enabling the poor and disabled to gain access to healthcare: Medicaid.

And, we have a perpetrator. 51 one of them, in fact. Sen. Mitch McConnell’s efforts to destroy healthcare for the poor, and his craven band of greedy sycophants disguised as public servants, are guilty of structural violence. We know what will happen if they get their way: 31, 16, or 15 million people will lose health insurance depending on which of their undemocratic bills pass. Most of these people will be poor, elderly, disabled, or children with severe health problems. Tens of thousands of unnecessary deaths annually can be predicted as a result.

This is structural violence with a face. It’s happening in real time, in front of all of us. We watch in horror at our Twitter streams or our Facebook news feeds at the latest news from Washington. We applaud and click the “like” button for our friends who share progressive articles cheering distant protests with arrests, sobbing, and screaming. And we go about our day, even if a little shaken.

All of this brings up another question: what obligation do we have to ACT? As people claiming the mantle of health and human rights workers, what responsibility do we bear to stand up and actively fight back against the obvious perpetrators of structural violence?

I would argue that for those of us making strong claims about the right to health comes great obligation to fight to protect and realize those rights. Certainly, this fight must come in many forms. But, it also certainly involves more than the ongoing clicktivism that we so often see as our primary mode of action.

I’ve made the 10-hour bus ride to DC and back on three separate occasions in the last three weeks, doing all that I can with my body, my money, and my effort to stop this heinous and undemocratic attempt to destroy healthcare for the poor. I don’t say this to be self-congratulatory.

I say this because my efforts have paled in comparison to members of the disabled community. Members of ADAPT, mostly wheelchair users with significant disabilities camped outside in front of the Russell Senate Office Building for three-straight nights and days, in the pouring, thunderous rain, to be seen and heard. They chained their chairs together in defiance of the Capitol Police in the center of the Hart Senate Office Building, sending their own thunderous roar through the halls of Congress. They did this because they knew it was life or death for them.

I say this because my efforts have paled in comparison to members of the LGBTQ community. Gay, lesbian, and transgendered people are leading this fight, putting their bodies on the line, getting arrested in civil disobedience, and putting themselves through the real risk, cost, and humiliation of jail time. They did this because they know what is at stake, having lived, or at least heard tales, of the fights of the 80’s and 90’s in the AIDS treatment struggle. And, they are facing the realtime threats of this administration in the ongoing fight for LGBTQ civil rights. Their heroism, borne of self preservation, protects us all.

I say this because my efforts have paled in comparison to the efforts of people of color: A mother, her teenage daughter, and their aunt from Georgia made the trek to D.C. because of their need to access to mental health and diabetes medicines to survive. An elderly man from Kentucky who needs support for his blood pressure medicine. Each on Medicaid and limited income, they are desperate to see these repeal efforts fail. And so, they are the ones turning out, showing up, and laying it all on the line.

Our community needs to be doing more. When I say, “our community,” I know that it’s a fraught term. But, let’s say the “health and human rights community.” We have resources, some time, and a hell of a lot of privilege and power at our disposal. I know that there are a million challenges and problems that we are dealing with on a nearly daily basis–our solidarity efforts in clinics and offices here, or in Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and Haiti will be ever present–but when clear and readily apparent structural violence is being advanced in front of our eyes, are we not obligated to act?

The only cure for structural violence, as Paul Farmer would say, is pragmatic solidarity. It’s about making common cause with the suffering and doing what needs to be done, as it’s needed, to practically advance their needs and demands.

This is a moment for pragmatic solidarity in America. And pragmatically, this means standing together in direct, non-violent, political action against the named perpetrators of structural violence: the leaders of the GOP.

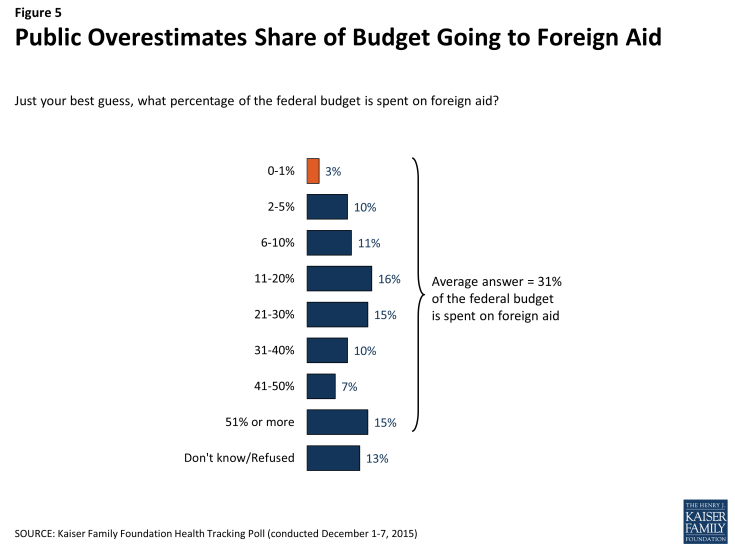

Here’s some exciting, positive news: colleagues at BU and I are launching a campaign to unionize graduate student workers at Boston University with the

Here’s some exciting, positive news: colleagues at BU and I are launching a campaign to unionize graduate student workers at Boston University with the