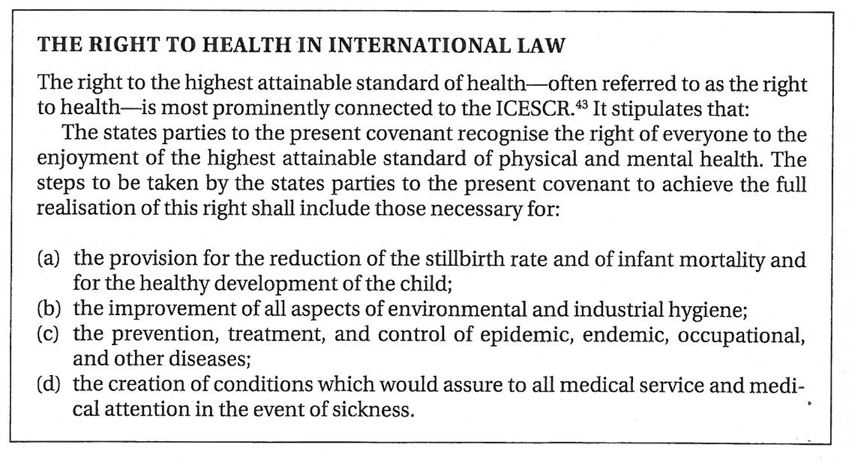

The right to health is a contested idea.[i],[ii] Increasingly, people agree that individuals have the right to be free from disproportionate risk of illness and early death.[iii] But, there are wide disagreements about what limits ought to be set around a right to health,[iv],[v] the practical mechanisms to protect the right to health,[vi],[vii],[viii] and what type of social and political strategies should be advanced to dismantle the historically, socially, and politically constructed barriers that limit our progress.[ix],[x],[xi],[xii],[xiii],[xiv] Because the right to health is at the center of a political contest that is historically and socially constructed, we need better theory about the social construction of the field of practice of global health. We also need a deeper understanding of the nature of social movements as sources of reform efforts and the practical organizational models that can grow such movements. This paper seeks to explore a research and organizing agenda that could better elucidate the social processes that underpin social movements and point toward more robust strategies to strengthen the right to health movement. This research and practice agenda should be “historically deep and geographically broad”[xv] and connect a critical study of the sociology of social movements,[xvi],[xvii] organizational theory,[xviii] and the field of practice of international development and global health.[xix],[xx],[xxi]

Social theory is used to contextualize and interpret the complex situations that characterize global health.[xxii],[xxiii] I will briefly share the work of three scholars that are rarely cited by global health practitioners but whose ideas provide a useful toolkit in studying and advancing the social movement for the right to health. I argue that there is a significant opportunity to deploy the social theory of Pierre Bourdieu in critical study of the field of practice of international development and global health, Doug McAdam’s political process model as a way to describe the emergence and growth of social movements, and Marshall Ganz’ community organizing and leadership pedagogy. I will then use these tools to provide a brief analysis of the current moment in the right to health movement and delineate some potential opportunities to strategize about future mobilization. I will also share early experiences in developing a grassroots community organizing strategy through the global health and social justice organization, Partners In Health (PIH). Working to create PIH Engage[xxiv] has helped us to understand how regular, concerned citizens, can work together to demand new modes of solidarity and redistribution from their communities and elected policy makers. Taken together, I hope to renew a discussion about modes of collective action that could continue to dismantle the deeply held double standards that prevent poor and marginalized people from being served by health care delivery systems.

Bourdieu and theory in the right to health movement

Pierre Bourdieu, a giant of 20th century sociology, built a theory of social action based on field research ranging from kinship relationships in isolated villages in Algeria to the social processes of production, circulation, and consumption of art and literature in 19th century France. His work sought to bring “reflexive”[xxv] sociological methods into building a whole understanding of social action: to “uncover the most profoundly buried structures of the various social worlds which constitute the social universe, as well as the ‘mechanisms’ which tend to ensure their reproduction and their transformation.”[xxvi] If the movement for the right to health is a process of social transformation, Bourdieu gives us a way to understand the ‘buried’ mechanisms that could be useful in hastening that transformation. Particularly useful to this understanding, Bourdieu describes three fundamental ideas that govern social action: field, habitus, and capital.

The field of social action is produced and reproduced by individuals and organizations that do not exist in a vacuum. Individuals and organizations exist in relationship to one another as they work in pursuit of shared aims, develop shared taken-for-granteds, grow shared interpretations, and come into competition for scarce resources. Loïc Wacquant offers a succinct definition: “a field is a patterned system of objective forces (much in the manner of a magnetic field), a relational configuration endowed with a specific gravity which it imposes on all objects and agents which enter it… Simultaneously, [it is] a space of conflict and competition, the analogy here being with a battlefield, in which participants vie to establish monopoly over the species of capital effective in it.”[xxvii] This social jostling and competition between actors in the field set up the terrain of a social game that is played out by social actors vying for dominance.

The habitus can be understood as an individual’s patterns of thoughts, behaviors, tastes, and actions acquired by their experienced participation in the social field of action. Bourdieu describes it as: “embodied history, internalized as a second nature and so forgotten as history—the active presence of the whole past of which it is the product.”[xxviii] Wacquant expands, “Cumulative exposure to certain social conditions instills in individuals an ensemble of durable and transposable dispositions that internalize the necessities of the extant social environment, inscribing inside the organism the patterned inertia and constraints of external reality… habitus is creative, inventive, but within the limits of its structures”.[xxix] The field of practice tends to produce individuals who have experienced and internalized the rules of the game as their habitus. Those individuals tend to then act in a way that reproduces the socially constructed field of practice, which, in turn, reinforces the internalized habitus of those in the field.

Finally, Bourdieu conceptualizes capital as multifaceted forms of field-specific power: economic, social, and symbolic. Economic capital is immediately transformable into money, but social capital (social relationships, friendships, partnerships), symbolic capital (prestige, clout), cultural capital (credentials, awards), and other forms of field-specific capital aren’t immediately transformable into financial resources. Non-economic forms of capital can be used to dominate fields of practice that organize society. Bourdieu compares each field to a market in which individuals and collective actors compete for the accumulation of the various forms of capital. In a field of practice, an agent with more capital will be successful over those actors with less capital.[xxx]

Again, Wacquant summarizes: “together, habitus and field designate bundles of relations. A field consists of a set of objective, historical relations between positions anchored in certain forms of power (or capital), while habitus consists of a set of historical relations ‘deposited’ within individual bodies in the form of mental and corporeal schemata of perception, appreciation, and action.”[xxxi] For us to build better theory and strategy for the right to health movement, we will need an effort to better construct an understanding of the field of practice of global heath within the broader field of international development and humanitarian relief.

Monika Krause has an important and penetrating analysis of the field of humanitarian reason and international development.[xxxii] In it, she takes a “Bourdieusian” approach to the description of the field of practice of humanitarian organizations. Organizations in this field, no matter how large, must make decisions about what to do, who to serve, and how best to serve them, in order to make their missions manageable. She describes this field as a set of relationships between large, international NGOs. These NGOs inhabit a shared social space and logic of practice that is governed by the pursuit and production of ideal “good projects”—those that can produce short term, quantifiable effects and serve groups that are relatively easy to assist. Krause argues that, “humanitarian relief is a form of production, transforming some things into other things. Agencies produce relief in the form of relief projects. As the unit of production is the project, managers seek to ‘do good projects.’ The pursuit of the good project develops a logic of its own that shapes the allocation of resources but also the types of activities that we are likely to see—and the type of activities we are not likely to see.”[xxxiii] The logic governing the production of the “good project” is driven by the habitus of “desk officers,” who are responsible for making these decisions and in doing so, practice a process of triage in response to resource constraints. International development financing and bilateral foreign aid programs create a global market of easily comparable “good projects” that are driven by principles of efficiency, cost-effectiveness, sustainability, and short term intervention: principles of neoliberalism.

These principles are generally incompatible with the goal of enabling governments, over the long term, to protect the right to health. The logic of “the good project” serves the practical function of transforming the role of the public sector through competitive contracting to for-profit and nonprofit private actors. The emergence of a global scale of comparison for relief projects drives the “projectification” of the field of global health and international development.[xxxiv]

If we accept Krause’s analysis of the current field of practice of humanitarian relief—one that drives the structured production and financing of narrowly defined good projects—organizations with a different logic might be able to mount an insurgent response. For instance, organizations with the explicit purpose to accompany ministries of health and governments to be effective in delivering on commitments to protect the right to health for their citizens could band together to demand new policies and financing mechanisms that are well suited to those ends.

This understanding may shed light on the ways that the history of neoliberal ideology is reproduced throughout financing, policy, and the organizational practices of international NGOs. It could also provide new insights for the network of organizations and individuals who strive for a different reality: one where the access to high-quality health care services is not a function of one’s ability to pay for them. To build this new reality, we need a social movement. But, first we must understand how social movements come about; especially how they emerge, expand, and decline.

McAdam and the emergence of social movements

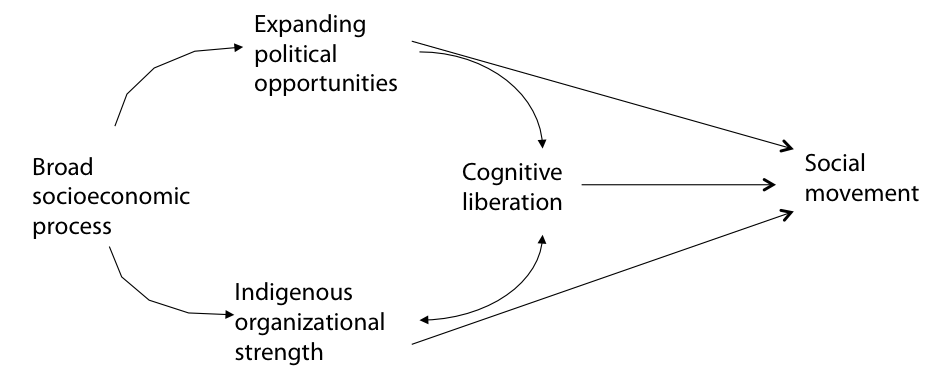

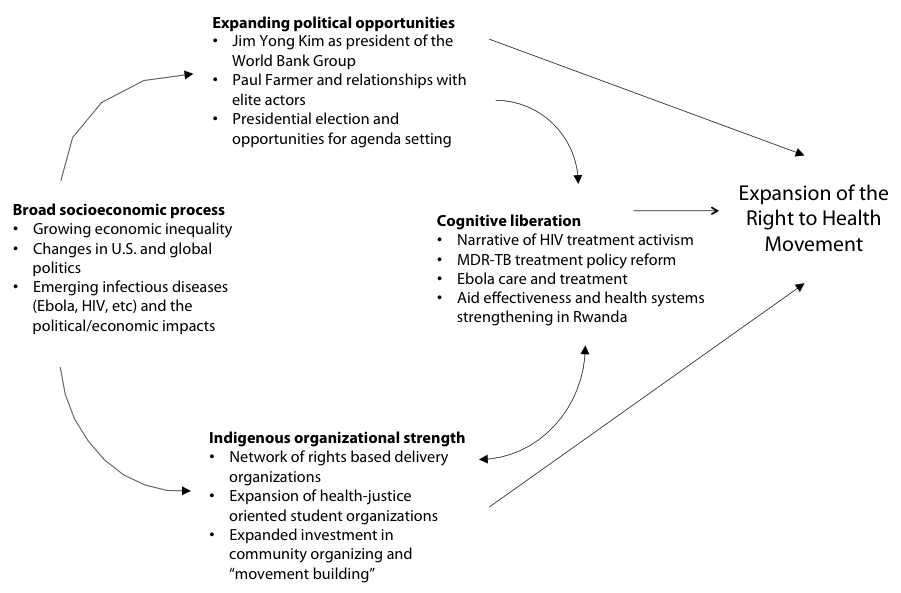

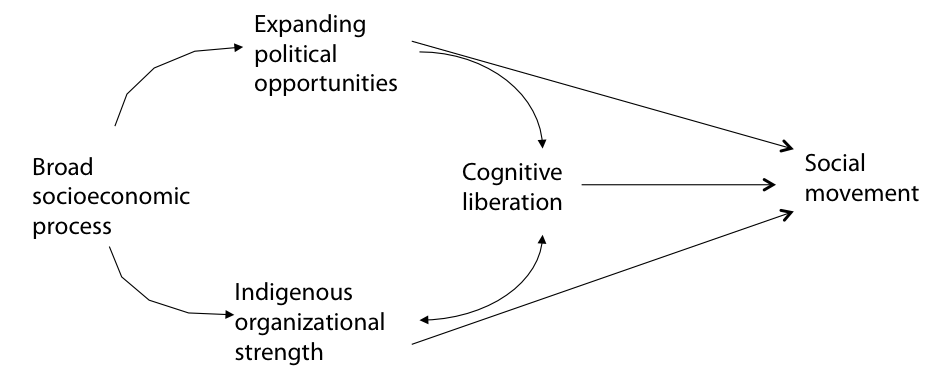

Doug McAdam’s political process model is a very useful framework for analyzing social movements. It identifies three sets of factors that are considered to be crucial for the emergence and development of social movements. First, organizational strength—the degree to which an aggrieved population is organized, formally or informally—is an essential component to the successful emergence of a social movement. Second, the collective assessment of political opportunities and chances of success is necessary to build momentum within grassroots organization. Finally, a degree of political alignment between the locally organized insurgent groups and the broader political and socioeconomic environment is necessary to be able to exploit spaces of opportunity for the social movement to expand. These three factors could be thought of as “degree of organizational readiness”, the level of “insurgent consciousness”, and finally the “structure of political opportunities.”[xxxv]

This model for conceptualizing social movement emergence can be visualized like the diagram below. Broad socioeconomic processes create the space (or remove space) and develop expanding (or contracting) political opportunities for insurgent groups to advance their movement. Yet, relying on an overly deterministic and structural set of factors to explain social movement emergence is insufficient to describe the range of movements and insurgency we see in the world. These structural factors enable a certain “structural potential” for political action, but they do not guarantee it. The final factor necessary for the emergence of social movements is the notion of “cognitive liberation”—the capacity for a group to transform their understanding, name their situation as unjust, and have the capacity to imagine an alternative reality that could be transformed together.[xxxvi] This cognitive liberation is a function of leadership, narrative, teamwork, and action.

Figure 1: Political process model for social movement emergence (McAdam, 1982)

Bourdieu’s notions of field and capital and McAdam’s political process model were brought together in an analysis of the reform process that produced a major shift in global multi-drug tuberculosis (MDRTB) treatment policy in the late 1990’s.[xxxvii] Victor Roy, in his Cambridge University master’s thesis, builds an understanding of the field of social action that led to the WHO’s focus on Directly Observed Therapy Short Course (DOTS)[xxxviii] as the single and only means of tuberculosis (TB) treatment from the 1970’s through the early 1990’s. This treatment regimen categorically excluded attempts to treat people with drug-resistant disease. Roy links this understanding of the field of global TB policy making to reform efforts made by Partners In Health and the organization’s strategy to demonstrate that MDRTB could be treated and cured effectively in poor settings like the slums of Lima, Peru. Leaders of PIH were able to mobilize field-specific scientific and cultural capital that became significant enough to alter the “cognitive cues” of those in the field. Together, they created a new “frame” of cognitive liberation that enabled potential allies and others to understand that the field was increasingly vulnerable to potential change.[xxxix]

The case of reform in MDRTB treatment policy is not, in the full sense, a “social movement”. Although, Roy’s analysis does demonstrate the significant opportunity to utilize the joint tools of Bourdieu and McAdam in studying reform efforts in global health policy, it is important to understand the shortcomings. The global tuberculosis epidemic has not abated and TB recently became the largest infectious disease killer in the world.[xl] Higher prices for key MDRTB drugs, lack of new pooled donor financing mechanisms, and perpetually weak health systems all present significant barriers to making progress in ending TB.[xli] Why has this reform effort been unsuccessful or, at least, incomplete?

Turning back to Bourdieu and McAdam we could understand the gap in terms of the types of capital that were chosen and available to PIH to mobilize their reform effort. The PIH team was able to enter the field of global TB policy making primarily due to their ability to mobilize the symbolic and scientific capital available because of their position within Harvard Medical School. The limited capital available to PIH structured and limited its strategy to focus primarily on technical policy changes—shifting DOTS protocol to DOTS-plus[xlii] and the development of the Green Light Committee at the WHO[xliii]—rather than a more broad-based political strategy. In Bourdieusian terms, the limitation could be understood as a lack of access to political capital that would be necessary to mobilize democratic pressure for larger redistributive financing mechanisms. Similarly, using McAdam’s political process model we would interpret this as a gap in local organizational strength of the reform movement. The PIH experience with TB stands in contrast to the AIDS treatment movement during which large numbers of activist groups were involved in grassroots political mobilization to exert local-level political pressure on key policy makers responsible for U.S. government global AIDS policy-making and funding.[xliv] These two historical examples and the theoretical tools of Bourdieu and McAdam are useful to understand the current moment in the movement for the right to health. But, if strong, local grassroots organizations are an important source of field-specific capital for global health reform, it is important to consider how they are built throughout social movements.

Marshall Ganz, organizing, and social movement leadership

Doug McAdam’s political process model gives us an elegant means of describing the emergence and growth of social movements, but it does not give concrete tools or specific practical guidance for individuals and organizations seeking to advance a particular struggle. Marshall Ganz’ work to build a practical and theoretically deep pedagogy of community organizing gives such a framework. Ganz’ organizing pedagogy enables individuals and organizations to identify, cultivate, and grow the capacities of leaders to advance collective action. Central to Ganz’ view of organizing is a deep notion of social movement leadership:

Leading in social movements requires learning to manage the core tensions at the heart of what theologian Walter Brueggemann calls the “prophetic imagination”: a combination of criticality (experience of the world’s pain) with hope (experience of the world’s possibility), avoiding being numbed by despair or deluded by optimism. A deep desire for change must be coupled with the capacity to make change. Structures must be created that create the space within which growth, creativity, and action can flourish, without slipping into the chaos of structurelessness, and leaders must be recruited, trained, and developed on a scale required to build the relationships, sustain the motivation, do the strategizing, and carry out the action required to achieve success.[xlv]

Successful social movement leadership is not something innate in individuals, it is something that can be learned and purposefully cultivated. Ganz has developed a robust practice of community organizing training[xlvi] that closely links a set of iteratively developed leadership practices. Relationships that are purpose-based and rooted in shared values, built on commitments, and grown from an exchange of resources and interests must be formed. New stories about the potential for a shared future that links values, emotion, and action into a “story of self,” a “story of us,” and a “story of now” must be told. Social movement leaders must develop creative strategies to successfully challenge those with more power by harnessing opportunities that arise due to environmental or context changes. Organizations must create purposeful structure amongst membership and organize time into campaigns for real action that grows power over time. Finally, teams must be developed that enable “snowflake-like” leadership structures and are capable of collaboratively deliberating, making decisions, and holding members accountable.[xlvii]

Moving from theoretical to organizationally pragmatic, Pierre Bourdieu, Doug McAdam, and Marshall Ganz give us an extremely useful set of ideas that should be more systematically deployed by scholars of and practitioners within the movement for the right to health. Bourdieu gives us a way to imagine the field of global health as a collection of actors working to expand their economic, social, and symbolic capital to control the “rules of the game”. The social movement for the right to health is a reform effort that seeks to shift the field away from neoliberal-dominated practice towards the aim of expanding state-protected rights. McAdam gives us a more specific way to view the social movement for the right to health. Using the political process model, we can analyze the structure of political opportunities that characterize the current moment for the right to health movement, the strength of local, grassroots organizations, and opportunities for “cognitive liberation” to imagine new realities of health care delivery in settings of poverty. Finally, Ganz gives a pragmatic model of local community organizing leadership training that civil society, grassroots community groups, and health care delivery oriented NGOs could adopt to grow the local capacities of actors in the struggle for the right to health.

The current moment: the urgent need for a revitalized movement

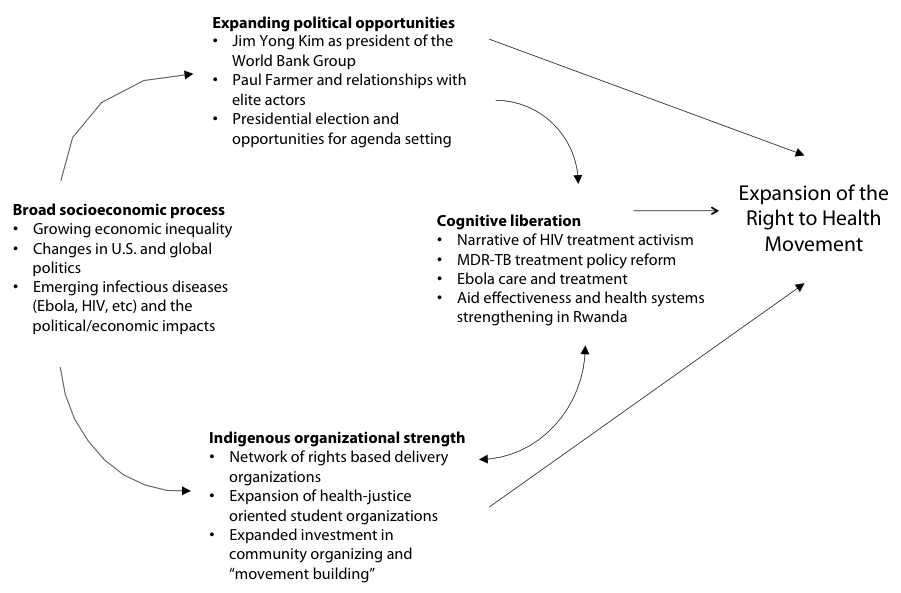

In certain circles, the current narrative around political opportunities for the right to health movement is pessimistic. In 2012, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation asked if we were nearing the “end of the golden age of global health”.[xlviii] Decrying the weakening of bipartisan leadership in global health and a precipitous decline in the number of direct action activist organizations focused on expanding global AIDS funding,[xlix] it may appear that the movement that spurred the creation of the Presidents Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB, and Malaria (The Global Fund) and the corresponding “delivery decade”[l] may be waning. However, four trends ought to give us hope.

First, the rise of universal health coverage (UHC) as a key global goal in the unanimously adopted UN Sustainable Development Goals[li] presents an important opportunity to create more political space for the right to health agenda. While this is an opportunity to demand access to quality health services far more broadly, it is also a contested concept that the right to health movement will need to make claims and build consensus around.[lii] A clear definition of UHC is necessary if we are to avoid the pitfalls of “Health for All” in 1987’s Alma-Ata Declaration which had high level leadership, but lacked sufficient political and budgetary space to realize its aims. It is clear that political will and engagement with civil society will be necessary to promote a rights-based approach and to institutionalize accountability to meet the needs of disadvantaged people.[liii]

A second important expanding political opportunity is the election of Dr. Jim Yong Kim as the president of the World Bank Group in 2012.[liv] Dr. Kim is a long-time right to health activist and his book Dying for Growth: Global Inequality and the Health of the Poor[lv] is a compilation of essays detailing how neoliberal policies deployed by the World Bank have harmed the health of poor and marginalized people and hampered states’ capacity to protect the right to health of their citizens. We should see his appointment as an opportunity to deploy this powerful position to imagine and actually create new financing mechanisms for the expansion of rights-based UHC in low-income countries.

Third, we are in an open U.S. presidential election in which candidates on both sides of the aisle must actively campaign. This presents a significant opportunity for right to health activists to engage with them on the campaign trail at small and mid-sized events in early-primary states. Commitments matter during campaigns (presidential campaigns in particular) when candidates are forced to take specific stances on issues and make pledges to quantifiable targets.[lvi] We have an opportunity to birddog[lvii], a tactic pioneered by AIDS activists, to gain commitments from politicians, many of whom have been significantly supportive of global health efforts in the past.

Finally, the Ebola epidemic in West Africa decimated already beleaguered health systems and killed more than eleven thousand people.[lviii] This has driven significant new discussion by policy makers on the role of U.S government development assistance in strengthening health systems in low-income countries.[lix] This framing—Ebola as a failure of already weak health systems—creates a powerful window for activists in the right to health movement to advance calls for new legislation that could enable new investments in health systems strengthening in poor countries.

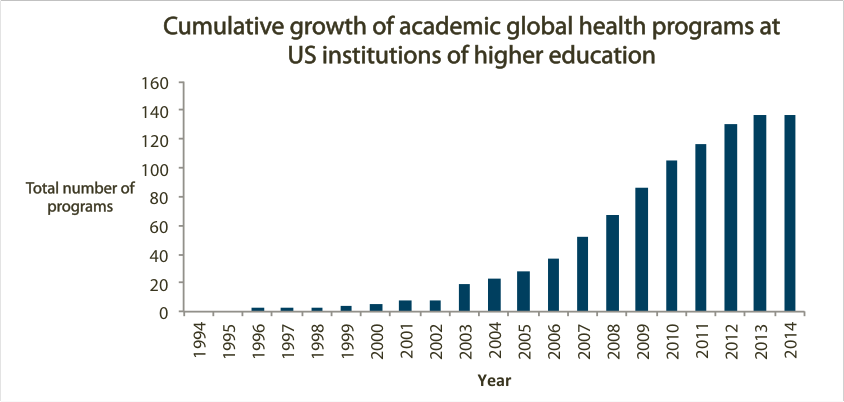

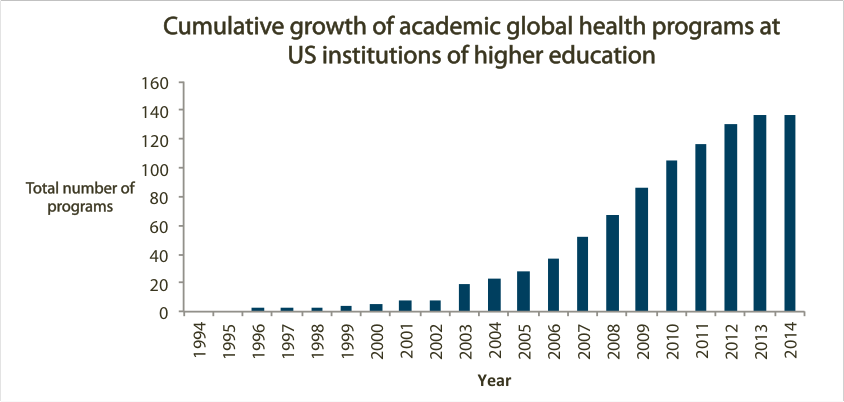

With these factors taken into consideration, the structure of political opportunities seems robust. But, what about the “structural potential” of locally organized constituencies and grassroots organizations? Globally, there is a growing network of global health delivery organizations working with a rights-based approach that seek to link delivery of services to accompaniment of the public sector and the generation of new knowledge.[lx],[lxi],[lxii],[lxiii],[lxiv] Additionally, a large network of student driven global health organizations[lxv],[lxvi],[lxvii],[lxviii],[lxix],[lxx],[lxxi] is moving forward and expanding global health academic programs at universities across the U.S.[lxxii],[lxxiii]

Figure 2: Growth of academic global health programs in the U.S. (majors, minors, study abroad programs, centers, and other formal programs dedicated to global health studies)

Although many of these student driven global health organizations are primarily service and education oriented, students are increasingly engaged in politics and activism.[lxxiv] Other global health activist networks are also working hard to advance justice-based policies in health.[lxxv],[lxxvi] All told, there seems to be growing “structural potential” in the right to health movement. There are more rights-based delivery organizations, more scholarship and university engagement in global health, and more potential global health justice activists than ever before. This structure can potentially be mobilized and directed toward the immense challenges faced by the right to health movement.

Figure 3: Political process model adapted to model the current moment in the right to health movement

Cognitive liberation—imagining new realities that are not immediately available to our socially constructed notion of reality, our habitus—is necessary to translate this structural potential into action and momentum for the right to health. From demonstrating an effective model for curing MDRTB in Lima, Peru[lxxvii],[lxxviii] to demonstrating that HIV treatment could be scaled in places of extreme poverty like central Haiti,[lxxix] PIH has worked to prove the possible in global health. Roy demonstrates how this proof, which is developed via the accrual of scientific capital, can catalyze policy reforms by altering the balance of power within a field of global health practice. These beacons of hope should serve as an antidote to despair in the midst of a culture that is socialized for scarcity.[lxxx] The future to the right to health movement is dependent on recasting the global health equity narrative towards one of possibility, growing new grassroots organizations that have the capacity to do political work, and creating the policy space for novel financing mechanisms.

PIH Engage: An organizing model in practice

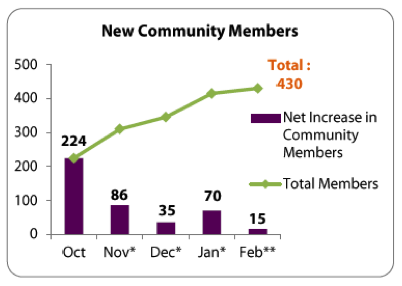

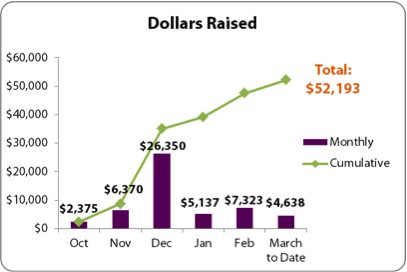

PIH Engage was launched in 2011 with the goal of harnessing the goodwill and enthusiasm for the right to health mission of Partners In Health that has grown during its 25 years of work fighting for global health equity. We are attempting to deploy Marshall Ganz’ model of community organizing—identifying and recruiting volunteer leaders, building community around that leadership, and generating power from that community—as a way to enable regular, concerned citizens, to work together to demand new modes of solidarity and redistribution from their communities and elected policy makers. So far, we have organized more than 90 teams of volunteer community organizers across the U.S. to engage their local communities, organize campaigns that raise funds for health care delivery efforts, and take on direct advocacy campaigns to create new policy space for rights-based financing mechanisms.

By the end of this year, we hope to have raised more than one million dollars from grassroots supporters, gained real commitments from political actors, from U.S. senators and representatives, as well as held demonstrations on dozens of college campuses and cities across the U.S., and moved forward a major new piece of health systems strengthening legislation. This work has a long way to go before it could be characterized as a social movement. And, even if successful, this effort will only be one small component of a much larger trans-national effort. But I believe that our experience so far shows that it has been a worthwhile investment. Hopefully PIH Engage can serve as a model for other rights-based healthcare delivery and advocacy organizations to strategize on how they could grow networks of organizers dedicated to advancing right to health campaigns in their local communities.

There is an opportunity to more systematically build theory and practice in the study of the right to health movement. Pierre Bourdieu gives us a theoretical framework with which to analyze the socially constructed field of practice that mediates and constrains the way organizations and individuals in the right to health struggle engage in the world. Doug McAdam gives us a model of social movement emergence and tools to analyze the structure of political opportunities, organizational strength, and narrative-driven cognitive liberation that can help direct strategic action. Finally, Marshall Ganz gives a concrete community organizing training and organizational framework that can be deployed by organizations to build a more powerful base of grassroots activists. If we take these linked frameworks as useful, we can see our collective work as growing the types of field-specific capital necessary to reorient the “rules of the game”, especially the way in which global health delivery gets financed. This field-specific capital could be grown through a wide variety of tactics: growing fundraising capacity, building the evidence base for effective rights-based delivery efforts, creating new narratives of possibility and beacons of hope, mobilizing the grassroots around this narrative of possibility, and developing grass-tops and grassroots political power capable of implementing new policy and financing mechanisms.

This essay is not meant as a comprehensive analysis of the right to health movement or a full review of the scholarship of social movements, community organizing, and their application to the right to health movement. It is however an attempt to sketch out an opportunity for expanded research and practice directed towards building a better understanding and more robust strategy for the practical effort of advancing a successful right to health movement.

Works Cited:

[i] Barlow, Phillip. “Health Care Is Not a Human Right.” British Medical Journal, 1999, 321.

[ii] Farmer P. Pathologies of power: rethinking health and human rights. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(10):1486-1496.

[iii] Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), G.A. Res. 217A (III) (1948), Art. xxv. Available at http://www.un.org/Overview/rights.html.

[iv] Kingston, Lindsey N, Elizabeth F Cohen, and Christopher P Morley. “Debate: Limitations on Universality: The ‘right to Health’ and the Necessity of Legal Nationality.” BMC International Health and Human Rights: 11.

[v] Boggio, Andrea, Matteo Zignol, Emesto Jaramillo, Paul Nunn, Geneviève Pinet, and Mario Raviglione. “Limitations on Human Rights: Are They Justifiable to Reduce the Burden of TB in the Era of MDR- and XDR-TB?”Health and Human Rights, 2008, 121.

[vi] Kim, Jim Yong, Paul Farmer, and Michael E Porter. “Redefining Global Health-care Delivery.” The Lancet, 2013, 1060-069.

[vii] Frenk, Julio. “The Global Health System: Strengthening National Health Systems as the Next Step for Global Progress.” PLoS Medicine 7, no. 1 (2010).

[viii] Binagwaho, Agnes, Cameron T. Nutt, Vincent Mutabazi, Corine Karema, Sabin Nsanzimana, Michel Gasana, Peter C. Drobac, Michael L. Rich, Parfait Uwaliraye, Jean Nyemazi, Michael R. Murphy, Claire M. Wagner, Andrew Makaka, Hinda Ruton, Gita N. Mody, Danielle R. Zurovcik, Jonathan A. Niconchuk, Cathy Mugeni, Fidele Ngabo, Jean De Dieu Ngirabega, Anita Asiimwe, and Paul E. Farmer. “Shared Learning in an Interconnected World: Innovations to Advance Global Health Equity.” Globalization and Health Global Health, 2013.

[ix] Gostin, Lawrence O. “A Framework Convention on Global Health.” JAMA, 2012.

[x] Forman, Lisa, Gorik Ooms, Audrey Chapman, Eric Friedman, Attiya Waris, Everaldo Lamprea, and Moses Mulumba. “What Could a Strengthened Right to Health Bring to the Post-2015 Health Development Agenda?: Interrogating the Role of the Minimum Core Concept in Advancing Essential Global Health Needs.” BMC International Health and Human Rights, 2013.

[xi] Gamson, Josh. “Silence, Death, and the Invisible Enemy: AIDS Activism and Social Movement “Newness”” Social Problems: 351-67.

[xii] Kapstein, Ethan B., and Joshua W. Busby. Kapstein, Ethan B., and Joshua W. Busby. AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations.

[xiii] Keshavjee, Salmaan. Blind Spot: How Neoliberalism Infiltrated Global Health. N.p.: n.p., n.d. Print.

[xiv] Epstein, Steven. Impure Science AIDS, Activism, and the Politics of Knowledge. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

[xv] Farmer, Paul. Pathologies of Power Health, Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

[xvi] McAdam, Doug. Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930-1970. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982.

[xvii] Ganz, Marshall. “Leading Change Leadership, Organization, and Social Movements.” Handbook of Leadership Theory and Practice: An HBS Centennial Colloquium on Advancing Leadership. Boston: Harvard Business, 2010.

[xviii] Davis, Gerald F. Social Movements and Organization Theory. New York, N.Y.: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

[xix] Krause, Monika. The Good Project: Humanitarian Relief NGOs and the Fragmentation of Reason. The University of Chicago Press, 2014.

[xx] Viterna, Jocelyn, and Cassandra Robertson. “New Directions for the Sociology of Development.” Annual Review of Sociology, 2015.

[xxi] Roy, Victor. “The Politics of Reform in Global Health Policy: The Case of Multi-Drug Resistant Tuberculosis, 1991-2001.” Dissertation for University of Cambridge, 2010.

[xxii] Kleinman, Arthur. “Four Social Theories for Global Health.” The Lancet, 2010, 1518-519.

[xxiii] Farmer, Paul. “Unpacking Global Health: Theory and Critique.” In Reimagining Global Health an Introduction. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013.

[xxiv] “PIH Engage.” PIH Engage. Accessed December 6, 2015. http://engage.pih.org/.

[xxv] Bourdieu, Pierre, and Loi Wacquant. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992. 36-46.

[xxvi] Ibid., 7.

[xxvii] Ibid., 17.

[xxviii] Bourdieu, Pierre. The Logic of Practice. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1990. 56.

[xxix] Bourdieu, Pierre, and Loi Wacquant. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992. 13-19.

[xxx] Ibid., 18.

[xxxi] Ibid., 16.

[xxxii] Krause, Monika. The Good Project: Humanitarian Relief NGOs and the Fragmentation of Reason. The University of Chicago Press, 2014.

[xxxiii] Ibid., 37

[xxxiv] Biehl, Joao. “Therapeutic Clientship: Belonging in Unganda’s Projectified Landscape of AIDS Care.” In When People Come First Critical Studies in Global Health. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013.

[xxxv] McAdam, Doug. Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930-1970. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982. 40-51.

[xxxvi] Ibid., 35.

[xxxvii] Roy, Victor. “The Politics of Reform in Global Health Policy: The Case of Multi-Drug Resistant Tuberculosis, 1991-2001.” Dissertation for University of Cambridge, 2010.

[xxxviii] World Health Organization (1998). Basis for the development of an evidence based case management strategy for MDR-TB within WHO’s DOTS strategy. Geneva: WHO, accessed at “World Health Organization & Library Information Networks for Knowledge Database (WHOLIS).” Web. March-May 2010.

[xxxix] Roy, Victor. “The Politics of Reform in Global Health Policy: The Case of Multi-Drug Resistant Tuberculosis, 1991-2001.” Dissertation for University of Cambridge, 2010.

[xl] World Health Organization (2015). World Tuberculosis Report (20th Edition). Retrieved from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/191102/1/9789241565059_eng.pdf?ua=1

[xli] Hwang, Thomas J., and Salmaan Keshavjee. “Global Financing and Long-Term Technical Assistance for Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis: Scaling Up Access to Treatment.” PLoS Medicine 11.9 (2014): e1001738. PMC. Web. 6 Dec. 2015.

[xlii] Farmer, Paul. “DOTS and DOTS-Plus. Not the Only Answer.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences: 165-84.

[xliii] Gupta, Rajesh, Alexander Irwin, Mario Raviglione, and Jim Kim. “Scaling-up Treatment for HIV/AIDS: Lessons Learned from Multidrug-resistant Tuberculosis.” The Lancet 363 (2004): 320-24.

[xliv] “The Troubled Path to HIV/AIDS Universal Treatment Access: Snatching Defeat from the Jaws of Victory?” In Global HIV/AIDS Politics, Policy and Activism: Persistent Challenges and Emerging Issues, edited by Raymond A. Smith, by Patricia Siplon. Praeger, 2013.

[xlv] Ganz, Marshall. “Leading Change Leadership, Organization, and Social Movements.” Handbook of Leadership Theory and Practice: An HBS Centennial Colloquium on Advancing Leadership. Boston: Harvard Business, 2010.

[xlvi] Ganz, Marshall. Marshall Ganz Teaching Comments. Accessed December 6, 2015. http://marshallganz.com/teachings/.

[xlvii] Ganz, Marshall. “Leading Change Leadership, Organization, and Social Movements.” Handbook of Leadership Theory and Practice: An HBS Centennial Colloquium on Advancing Leadership. Boston: Harvard Business, 2010.

[xlviii] Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. “Financing Global Health 2012: The End of the Golden Age?” Seattle, WA: IHME, 2012.

[xlix] Morrison, J. Stephen. “The End of the Golden Era of Global Health?” Editorial. Center for Strategic and International Studies. Web. <http://csis.org/files/publication/120417_gf_morrison.pdf>.

[l] Farmer, Paul E. “Chronic Infectious Disease and the Future of Health Care Delivery.” New England Journal of Medicine, 2013, 2424-436.

[li] “Goal 3.8 in the UN Sustainable Development Goals.” Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. Accessed December 6, 2015. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/topics.

[lii] O’Connell, Thomas, Kumanan Rasanathan, and Mickey Chopra. “What Does Universal Health Coverage Mean?” The Lancet: 277-79.

[liii] Ibid.

[liv] Garrett, Laurie. “Dr. Kim and the World Bank’s Health Role.” Council on Foreign Relations. April 13, 2012. Accessed December 6, 2015. <http://www.cfr.org/international-organizations-and-alliances/dr-kim-world-banks-health-role/p27952>.

[lv] Kim, Jim Yong. Dying for Growth: Global Inequality and the Health of the Poor. Monroe, ME.: Common Courage Press, 2000.

[lvi] Nelson, Libby. “Campaign Promises Matter.” Vox. November 27, 2015. Accessed December 9, 2015. http://www.vox.com/2015/11/27/9801800/politicians-keep-campaign-promises.

[lvii] Davis, Paul. “Five Questions For: ‘Take the Money Out’ Activist Paul Davis about Disrupting a National Journal Event.” Interview by David Ferguson. Raw Story 6 Sept. 2012. Accessed October 30, 2015. <http://www.rawstory.com/2012/09/five-questions-for-take-the-money-out-activist-paul-davis-about-disrupting-a-national-journal-event/>.

[lviii] “2014 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa – Case Counts.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. December 4, 2015. Accessed December 6, 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/2014-west-africa/case-counts.html.

[lix] “United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations.” Hearing. Accessed December 6, 2015. http://www.foreign.senate.gov/hearings/the-ebola-epidemic-the-keys-to-success-for-the-international-response.

[lx] “We Have Everything We Need to End Child Mortality Now.” Muso. Accessed December 6, 2015. http://www.projectmuso.org/.

[lxi] “Hope Through Health.” Hope Through Health Home Page. Accessed December 6, 2015. http://hthglobal.org/.

[lxii] “Home | Possible.” Possible Health. Accessed December 6, 2015. http://possiblehealth.org/.

[lxiii] “Home Page.” Last Mile Health. Accessed December 6, 2015. http://lastmilehealth.org/.

[lxiv] “PIVOT Health.” PIVOT Home. Accessed December 6, 2015. http://pivotworks.org/.

[lxv] “GlobeMed | Developing 21st Century Leaders for Global Health.” GlobeMed. Accessed December 6, 2015. http://globemed.org/.

[lxvi] “Global Health Corps Home.” Global Health Corps. Accessed December 6, 2015. http://ghcorps.org/.

[lxvii] “Student Global AIDS Campaign (SGAC) Home.” Student Global AIDS Campaign (SGAC). Accessed December 6, 2015. http://www.studentglobalaidscampaign.org/.

[lxviii] “Universities Allied for Essential Medicines.” Universities Allied for Essential Medicines. Accessed December 6, 2015. http://uaem.org/.

[lxix] “Help @end_7 End 7 Diseases and Lessen Suffering for over ½ a Billion Kids in the Developing World.” END 7 Home. Accessed December 6, 2015. http://www.end7.org/.

[lxx] “Join PIH Engage.” PIH Engage. Accessed December 6, 2015. http://engage.pih.org/.

[lxxi] “Home – Timmy Global Health.” Timmy Global Health. Accessed December 6, 2015. https://timmyglobalhealth.org/.

[lxxii] Merson, Michael H. “University Engagement in Global Health.” New England Journal of Medicine: May 1, 2014. 1676-678.

[lxxiii] Matheson, Alastair I., Judd L. Walson, James Pfeiffer, and King Holmes. Sustainability and Growth of University Global Health Programs. Rep. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2014.

[lxxiv] Stolberg, Sheryl Gay. “Colleges Are Producing New Style of AIDS Activist.” The New York Times. November 30, 2010.

[lxxv] “Health Global Access Project (Health GAP).” Health Global Access Project (Health GAP). Accessed December 6, 2015. http://www.healthgap.org/.

[lxxvi] “RESULTS | Homepage.” RESULTS. Accessed December 6, 2015. http://www.results.org/.

[lxxvii] Shin, Sonya, Jennifer Furin, Jaime Bayona, Kedar Mate, Jim Yong Kim, and Paul Farmer. “Community-based Treatment of Multidrug-resistant Tuberculosis in Lima, Peru: 7 Years of Experience.” Social Science & Medicine, 2004, 1529-539.

[lxxviii] Roy, Victor. “The Politics of Reform in Global Health Policy: The Case of Multi-Drug Resistant Tuberculosis, 1991-2001.” Dissertation for University of Cambridge, 2010.

[lxxix] Farmer, P, Léandre, F, Mukherjee, J, Gupta, R, Tarter, L, Kim, J Y. “Community-based treatment of advanced HIV disease: introducing DOT-HAART (directly observed therapy with highly active antiretroviral therapy)” Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 2001, Vol.79(12), pp.1145-51

[lxxx] Farmer, Paul. “An Anthropology of Structural Violence.” Current Anthropology, 2003, 305-25.