“The past of social science is always one of the main obstacles to social science.”

– Pierre Bourdieu, Sociology in Question (1993)

Introduction:

In this semester’s classical social theory course Prof. John Stone remarked: “if nothing else, I hope that this course has given you a healthy skepticism of placing too much faith in social theory.” After closely reading classical theorists from Montesquieu to Veblen, I can see why: these thinkers and their grand ideas were products of their time and circumstance. In Postcolonial Thought and Social Theory, Prof. Julian Go makes a compelling argument for the problematic ontology and epistemology set out by classical theoreticians. They were often (in hindsight) obviously shaped by their cultural and historical moments and were therefor subject to their own biases and blind spots. More sociologically, we could say that these ideas were social productions of interested actors, most of whom were of privileged classes that increasingly deployed concepts to make sense of and manage threats to social order from below their ranks. In much of their research, early sociologists also tended to “reproduce the imperial gaze” by which empires operated, reproducing and reifying stereotypes and systems of power relations within and between social groups (Go, 2016, Chapter 2).

Sociology’s foundation was developed during the Enlightenment and rested on three central concepts: humanism, that there is a universal human nature that can be improved based on Reason; universalism, that the world is made up of basic unalterable truths that can be understood independent of space and time; and positivism, the reliance on scientific method as the best approach for understanding the world in general. This ontological way of knowing and epistemological lineage has come to shape how the discipline of sociology has evolved, leading Go and others to call for new social theory agenda that brings a subaltern (postcolonial) and relational perspective to understanding the social world.

Emerging from the elite intellectual community of France in the 1960’s, Pierre Bourdieu is one such relational sociologist. A giant of 20th century sociology, Bourdieu built a theory of social action based on field research ranging from kinship relationships in isolated villages in Algeria to the social processes of production, circulation, and consumption of art and literature in 19th century France. His work sought to bring “reflexive” sociological methods into building a whole understanding of social action: to “uncover the most profoundly buried structures of the various social worlds which constitute the social universe, as well as the ‘mechanisms’ which tend to ensure their reproduction and their transformation” (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992). Bourdieu’s work seeks to develop a way to understand the “buried” mechanisms that undergird social life and tend to create and reproduce dominance and domination in society.

Although Bourdieu’s perspective is by no means a “southern” theory—Bourdieu was born in southern France and ascended to the pinnacle of elite intelligentsia in the French academe—his work does, at first glance, appear to be a way to obliterate the antimonies and dichotomies that ontologically and epistemologically reproduce power relations through what he would call symbolic violence. In this way, he attempts to challenge and subsume some of the most pressing theoretical problems of classical social theory: the dilemma of structure vs. agency, the objective vs. subjective divide in epistemology, and the ontological problem of the individual or structural locus of agency.

In seeking to make this course not simply a philological exercise, my goal in this paper is to explore the classical theoretic roots of Bourdieu’s work. In doing so, I hope to assess whether he is successful in breaking with the “imperial episteme” and dissolving the age-old antimonies that bedevil social theory. Do Bourdieu’s “structuring structures” get up and out of the historically constructed and epistemologically limited structures of classical social theory?

Specifically, I seek answers to four broad sets of questions: 1) Who were the principal classical theorists referenced by Bourdieu (implicitly and explicitly)? 2) What ideas were most important in the formation of his theory of practice and social life? 3) How do these foundational concepts relate to Bourdieu’s ontology of the social and to his epistemological approach to social science? 4) Finally, given the problematic roots of classical social theory, does Bourdieu’s repackaging of classical ideas into a reflexive and relational sociology give us a “way out” of the colonial-epistemological bind?

I will start with a very brief background on Bourdieu’s biographical, educational, and historical context, then proceed to an explanation of his core theoretical concepts (field, capital, and habitus) and their applications, break down their most important conceptual linkages with classical social theorists, and then I will comment on their implications for Bourdieu’s epistemological project. I will conclude with an assessment of Bourdieu’s field-theoretic approach to relational sociology and its ability to emancipate social theory from the shackles of symbolic and historic violence.

Bourdieu’s Roots

Bourdieu’s biography matters only insofar as it helps to explain his internalized dispositions and socialized perspectives—his habitus, as he would put it. He began his journey being born in 1930 to a lower-middle class family in Deguin, a small town in the south of France. His father was the town postal worker and it was a fairly inauspicious start. This is important only in juxtaposition to the fact that he would rise to the pinnacle of French intellectual life.

More important than his early biography was his identification as a brilliant student who was able to gain entrance into École Normale Supérieure (ENS), one of the most prestigious universities in all of France. While there, he was able to study under the great structural Marxist, Louis Althusser, he had Jacques Darrida and Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie as classmates, and was enveloped in classical and contemporary social theory and philosophy. He quick rose through the ranks of French intellectuals.

For these reasons, he would always feel like something of an outsider in the upper reaches of French society. This history and how it shaped his internal dispositions and priorities (habitus, which I will describe below) is important because it trained his focus on the ways that people (especially academics) shaped and defined the terms of debate, doing symbolic violence through dominating the ways knowledge was created. Loic Wacquant has an interesting perspective on this: “Back in 1981, he [Bourdieu] had seriously envisaged turning down the Chair in Sociology to which he was eventually elected at the Collège de France, the country’s top research institution, because he could not resolve to go through the official pageantry of the inaugural lecture. He assumed the position only after he had figured out how to turn the event onto itself and make it over into a performative paradigm for reflexive sociology by delivering a ‘Lecture on the Lecture’ in which he would dissect the social springs and underscore the symbolic arbitrariness of the very ‘rite of consecration’ he was enacting.” (Wacquant, 2013). Perhaps, because of his insider/outsider experience and the ways it shaped his own habitus, Bourdieu was hyper vigilant in identifying and exposing imbalances in symbolic power.

During this time, ENS served as a breeding ground for “young Durkheimians.” Indeed, he was able to carefully read, write on, and even began to lead lectures on Marx, Weber, and Durkheim while there. Additionally, he began to work closely with and was mentored by the illustrious sociologist, philosopher, and political scientist Raymond Aron as he launched his European Center for Historical Sociology. It was in this remarkable intellectual milieu that he began to form his ideas about the social world that would begin to take more formal shape while doing ethnography in Algeria (Swartz, 1997, 16).

Central to his philosophical development was his engagement with the tension animated primarily between two important French intellectuals: Jean Paul Sartre and Claude Levi-Strauss. These two academics embodied a confrontation of ideas—two extremes on an intellectual spectrum. Sartre was an engaged humanist and Levi-Strauss represented more of a detached scientist. As we will see, for Bourdieu, this tension proved fruitful and extended beyond just their styles of intellectual and scientific engagement, it also represented antithetical poles of basic opposition between subjectivism and objectivism in philosophy and social science. This would be a central focus for the future of Bourdieu’s scholarship (Brubaker, 1985).

Another important early philosophical influence was Gaston Bachelard who theorized on the philosophy of science in the midst of the scientific revolutions of the development of relativity theory and quantum mechanics. For Bachelard, “scientific knowledge is ‘constructed’ and ‘dialectical’ knowledge, one that does not arrive at final truths but proceeds as an ongoing project of correction and rectification of past errors” (Swartz, 1997, 31). He argues that in the face of radical scientific advances, the positivist philosophy of the past will not suffice and instead scientists must adopt a “dialectical reason”—an early example of “reflexive epistemology,” and a notion that Bourdieu would lean on heavily in trying to confront the productive tension between Sartre’s existential subjectivism and Levi-Strauss’s structuralism / objectivism.

Finally, as mentioned before, Marx, Weber, and Durkheim all played extremely important roles in shaping the contours of most of Bourdieu’s concepts and theoretical strategies. I will discuss their important contributions once I have sketched the key components of Bourdieu’s approach. As an aside (I will not be exploring these thinkers in this paper) theorists and philosphers such as Ausin, Cassirer, Heidegger, Husserl, Merleau-Ponty, and Wiggenstein also played somewhat important roles in shaping Bourdieu’s thinking (Swartz, 1997, 30).

Bourdieu’s Theoretical Apparatus:

We will start with a brief overview of Bourdieu’s key concepts that he developed over many years of teaching, fieldwork, systematic scholarship and engaging with some of the leading intellectuals of his age.

The concept of field brings a spatial / geographic element to Bourdieu’s theory of social practice. The field of social action is produced and reproduced by individuals and organizations that do not exist in a vacuum—they exist in relationship with one another. Individuals and organizations also compete with one another as they work in pursuit of shared aims, develop shared taken-for-granteds, grow shared interpretations, and fight over scarce resources. Loïc Wacquant offers a succinct definition: “a field is a patterned system of objective forces (much in the manner of a magnetic field), a relational configuration endowed with a specific gravity which it imposes on all objects and agents which enter it… Simultaneously, [it is] a space of conflict and competition, the analogy here being with a battlefield, in which participants vie to establish monopoly over the species of capital effective in it” (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992, 17). This social jostling and competition between actors in the field set up the terrain of a social game that is played out by social actors vying for dominance.

The habitus can be understood as an individual’s patterns of thoughts, behaviors, tastes, and actions acquired by their experienced participation in the social field of action. Bourdieu describes it as: “embodied history, internalized as a second nature and so forgotten as history—the active presence of the whole past of which it is the product.” (Bourdieu, 1990, 56). Wacquant expands, “Cumulative exposure to certain social conditions instills in individuals an ensemble of durable and transposable dispositions that internalize the necessities of the extant social environment, inscribing inside the organism the patterned inertia and constraints of external reality… habitus is creative, inventive, but within the limits of its structures”. (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992, 13-19) The field of practice tends to produce individuals who have experienced and internalized the rules of the game as their habitus. Those individuals tend to then act in a way that reproduces the socially constructed field of practice, which, in turn, reinforces the internalized habitus of those in the field.

Finally, Bourdieu conceptualizes capital as multifaceted forms of field-specific power: economic, social, and symbolic. Economic capital is immediately transformable into money, but social capital (social relationships, friendships, partnerships), symbolic capital (prestige, clout), cultural capital (credentials, awards), and other forms of field-specific capital aren’t immediately transformable into financial resources. Non-economic forms of capital can be used to dominate fields of practice that organize society. Bourdieu compares each field to a market in which individuals and collective actors compete for the accumulation of the various forms of capital. In a field of practice, an agent with more capital will be successful over those actors with less capital (Ibid., 15). Again, Wacquant summarizes: “together, habitus and field designate bundles of relations. A field consists of a set of objective, historical relations between positions anchored in certain forms of power (or capital), while habitus consists of a set of historical relations ‘deposited’ within individual bodies in the form of mental and corporeal schemata of perception, appreciation, and action.” (Ibid., 16)

Bourdieu’s Classical Theory Roots

Bourdieu’s linked theoretical and empirical project has been one of the widest-ranging, diverse, and inventive since World War II. Publishing more than 25 books and 260 articles over a 40-year period, he did away with disciplinary boundaries and sought to tackle and reformulate some of the most challenging questions of the social sciences. Bourdieu stands out in his ability to draw from sociology, anthropology, history, linguistics, philosophy, political science, aesthetics, and literary studies and in his efforts to combine methodological approaches such as detailed ethnographic fieldwork, constructing statistical models, and abstract theoretical formulation. His work has been driven by a singular commitment to the idea that there could be a unified political economy of practice and that symbolic power could be understood in a way that could dissolve central social science puzzles: the challenge of analyzing micro and macro-level processes together, the difficulty of co-explaining social structure and the feeling of individual agency, and objective / subjective ways of interpreting meaning in the world (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992, 2-6). His goal is to build a truly “philosophical anthropology” in which social reality and ideas about human living would not just be built off of speculation and reflection on the universal attributes of humanity, but would be linked to a rigorous process of inquiry with the epistemic authority of scientific method (Peters, 2012).

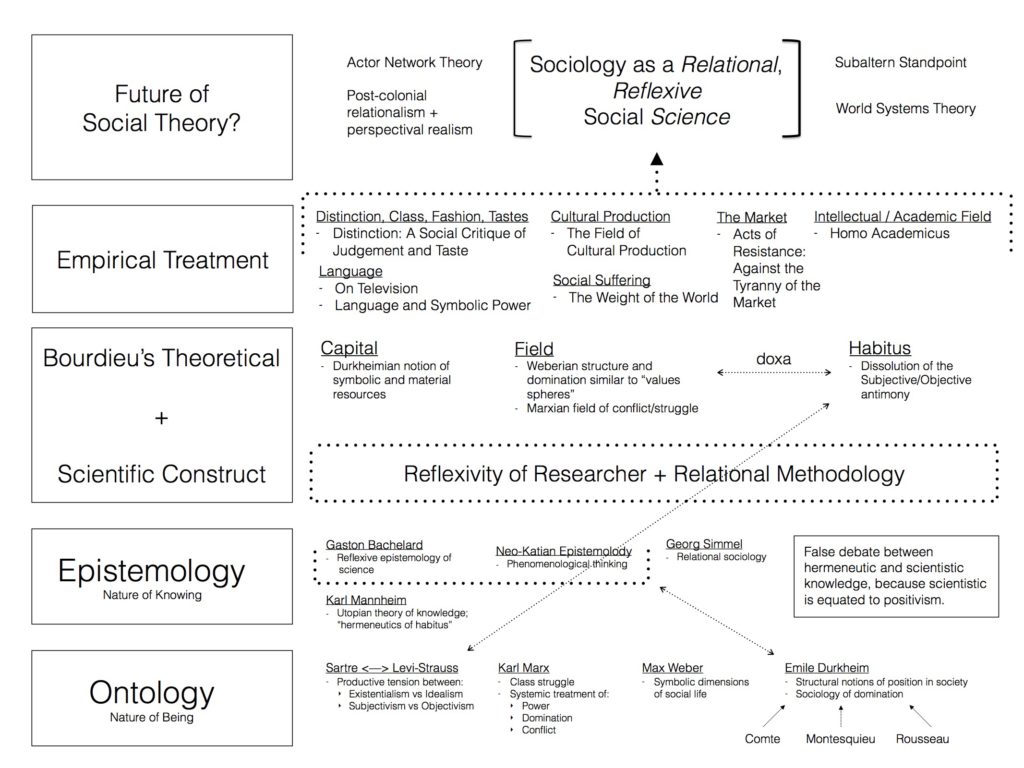

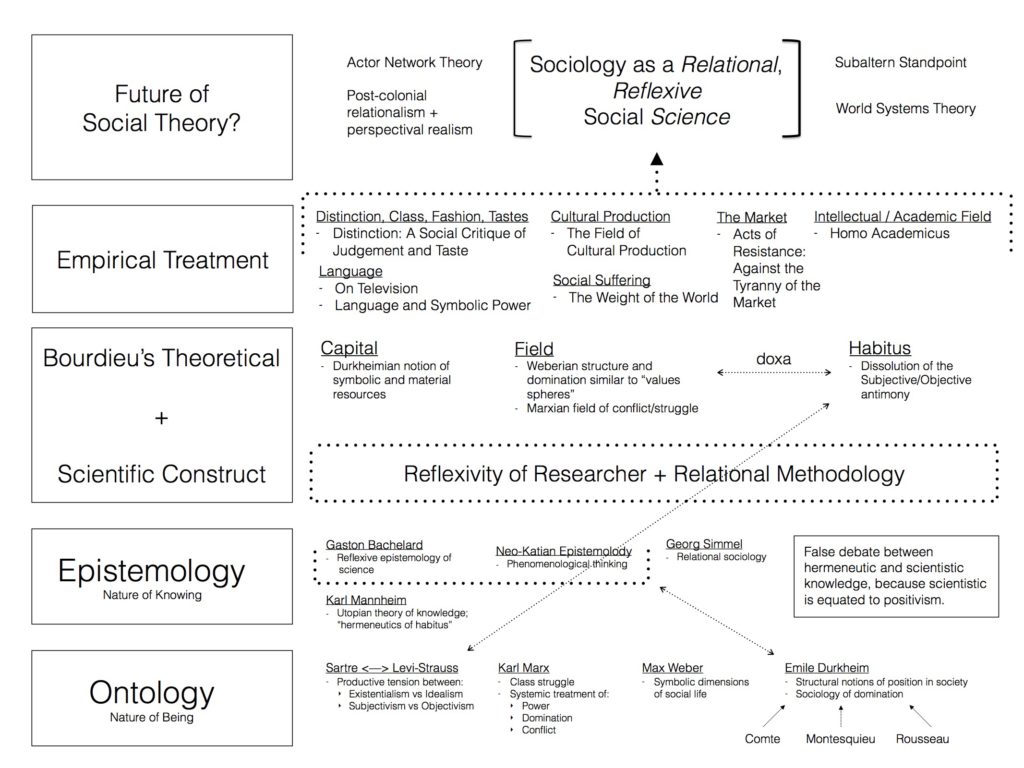

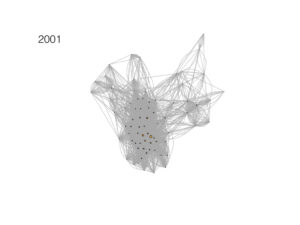

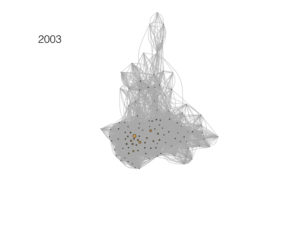

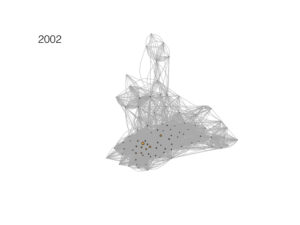

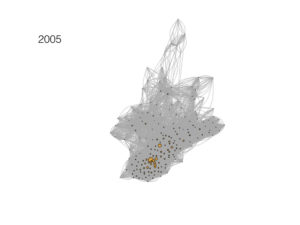

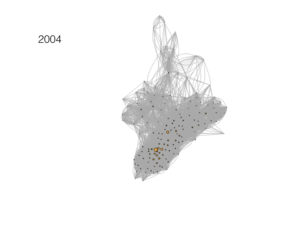

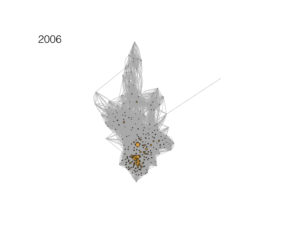

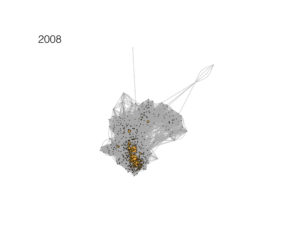

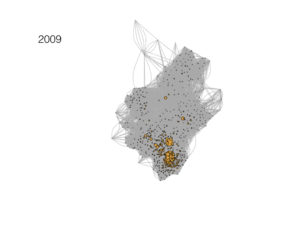

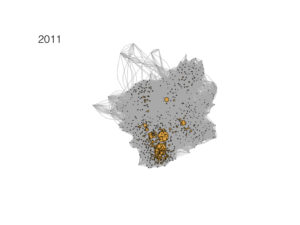

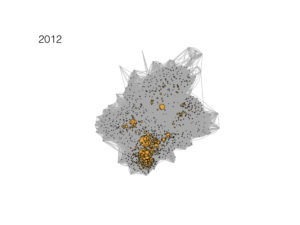

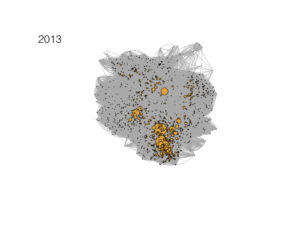

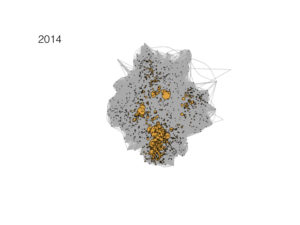

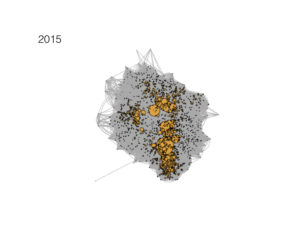

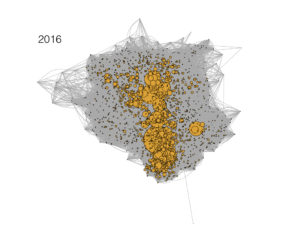

Based on my readings of Bourdieu and a host of other books and articles dissecting his ideas and influences, I constructed the diagram below as a schematic of the ontological and epistemological roots of his core ideas. I have tried to demonstrate how various classical theorists’ ideas have served as building blocks and have been recombined to form Bourdieu’s central structuring structures. These theoretical constructs have given him the platform to systematically explore a wide variety of social phenomena empirically. My question then will be to assess whether he has truly constructed a theoretical base that can free social theory from the historical legacy of colonialism and symbolic domination.

Figure 1. Diagram of Bourdieu’s Influences and Theory

Synthetic Ontology

Bourdieu’s way of thinking about the nature of existence of the social world, his ontological vision, can best be described as synthetic, relational, and non-Cartesian. It “refuses to split subject and object, intention and cause, materiality and symbolic representation.” (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992, 5). Wacquant goes on:

“A total science of society must jettison both the mechanical structuralism which puts agents “on vacation” and the teleological individualism which recognizes people only in the truncated form of an “oversocialized ‘cultural dope’” or is in the guise of more or less sophisticated reincarnations of homo economicus. Objectivism and subjectivism, mechanicalism and finalism, structural necessity and individual agency are false antimonies. Each term of these paired opposites reinforces the other; all collude in obfuscating the anthropological truth in human practice.” (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992, 10).

One can see Bourdieu’s distain for artificial antimony throughout his work and his almost obsessive attempts to destroy these false divisions. Biographically and intellectually, it is possible to trace the roots of this obsession to his engagement with the intellectual battles between Jean-Paul Sartre and Claude Levi-Strauss and their followers who dominated much of the intellectual landscape in France in the wake of World War II. The tensions at the heart of this intellectual battle were philosophical/ontological, aesthetic/stylistic, and political.

Stylistically, Sartre represented the classic French “total intellectual”; he lived in such a way that he had complete alignment between his intellectual, scholarly, political, and practical engagements. As a public intellectual, he felt that he must “miss nothing of our time” (Swartz, 1997, 36). Conceptually, Sartre’s existentialism and subjectivism represented one distinct way of understanding social life: the carefree individual, creative and self-determining. Conversely, Levi-Strauss’ aesthetic was one of the professional academic, rather than the public-facing, politically active, celebrity-intellectual. His brand of causally-powerful social structures and formal view of the ways that social structures shape human thought could not be more in tension with Sartre’s (Swartz, 1997, 39-40).

This real-life, socially constructed rivalry and its effects in reifying an important antimony in the philosophy of human existence was an important shaping force for Bourdieu’s early thinking and his forming professional style and methodological commitments as well. It developed within him the motivation to try to build an understanding of the social world that was not simply about immutable social structures and sets of rules that govern the actions of social groups and could be measured in a statistically positivistic way. Nor was social life to be understood as the existentialists would have it: as a collection of individual agents freely floating through life with complete autonomy of spirit and freedom of will. As we will see, this tension filled relationship, and these polarized conceptual apparatuses, form a creative space which could very well be the roots of one of his most important conceptual tools: the habitus, as described previously.

In addition to Bourdieu’s formative encounter with the intellectual and stylistic dualisms of Sartre and Levi-Strauss, Bourdieu was also a close scholar of Marx, Weber, and Durkheim, and their formative ideas became very important, in different ways, to Bourdieu’s formulation of theory and method in understanding the social world. Sometimes scholars have viewed Bourdieu’s ideas as having been influenced by Weber, Durkheim, and Marx in equal proportion: a focus on the symbolic dimension from the first, a sociology of domination from the second, and an interest in class struggle from the third (Riley, 2015). However in my reading, Durkheim’s approach and work weighs most heavily in Bourdieu’s formulations of theory.

In particular, Durkheim’s understanding and description of the symbolic dimensions of social life and its power to effect social action was highly influential for Bourdieu. Although Bourdieu would distance himself from Durkheim’s highly positivistic method, statistically measuring patterns of variation in the social world (Durkheim, 1951), he would come to adopt and utilize the idea of “social facts as things.” Particularly key is Durkheim’s somewhat “neo-Kantian” epistemological approach, which we will come to soon (Robbins, 2003). Additionally, Durkheim’s view of understanding of the ways symbolic manipulation plays into social life is central in Bourdieu’s conceptions of less material forms of capital and the ways these forms of power can render symbolic domination within fields of struggle (Swartz, 1997, 46-48; Durkheim & Fields, 1995). He also came to identify with Durkheim’s style (as he tended to resonate stylistically with Levi-Strauss) and came to view sociology as a professional scientific discipline.

Max Weber’s thinking also loomed large in Bourdieu’s foundational ontology. Specifically, Weber’s tools to describe symbolic resources and practices were central to Bourdieu’s understanding of symbolic capital and domination (Swartz, 1997, 41). At the heart of understanding Bourdieu’s notion of field as a contested social space of material and symbolic domination is Weber’s “value spheres” (Bruun, 2008). For Weber, values spheres were linked to the philosophical triad of truth, morals, and culture: things we know, what we ought to do, and what we want to do. They were spaces or domains of social life governed by “inherent laws” pertaining to these fields or systems. These value spheres can be linked to Bourdieu’s fields as empirically identifiable spaces of social relations, historical periods, or geographical periods—not some settled systemic criterion (Ibid.). Although perhaps oversimplified, scholars have suggested that Bourdieu’s fields resemble quasi-Marxist Weberian value spheres. By “subjectivizing” Marxist thought with Durkheimian concerns with the forms and functions of symbols, and Weber’s work on symbols and their concrete power as well as a more formal structuralism, Bourdieu has attempted to unify some of the most frustrating divisions in social theoretical thought and advance a more fully-fledged ontological view on social life (Brubaker, 1985).

Reflexive Epistemology

Where things become particularly interesting in is how these base-level ontological influences become recombined into Bourdieu’s conception of how we can come to know things about the social world. One aspect that makes Bourdieu so unique in my view is his seemingly complete and parsimonious view of the philosophical nature of social life and his practical methodological process of generating knowledge about its formation and function. At the same time, Bourdieu was pragmatic and his views evolved and morphed over the course of his studies. Throughout his career, Bourdieu was prepared to use whatever sociological explanations were to hand and which seemed to fit plausibly the historical, ethnographic records with which he was working (Robbins, 2003). By seeking to obliterate the distinctions dividing the existentialists from the structuralists and bringing together a synthesis of key concepts uniting the classical theorists, Bourdieu needed not just new ideas, terminology, and ways of thinking about social life. He needed a new of way of doing social science work. This is accomplished through linking his synthetic ontology with a highly reflexive epistemology of science and knowledge.

The keys to Bourdieu’s epistemology of the social are also at the roots of Durkheim’s thinking. Although as previously discussed, Bourdieu rejected Durkheim’s highly positivist philosophical leanings and methods, he embraced his “neo-Kantian” approach which brought in a phenomenological way to understanding the mind and subjective experience of people in social life (Ibid.). For Bourdieu, all social analysis involves the analysis of a system of relations within which individuals operate and through which their individualities are defined. At the same time, those producing social analysis are themselves embedded within a system of relations, which have a shaping effect on the researchers own perspectives, dispositions, resources, and opportunities. The fundamentally relational nature of social life and the correspondingly relational nature of the productive work of social analysis, demands a completely relational nature of knowing. Producing knowledge requires turning back on oneself, reversing the “scholarly gaze” to explore the system of relations and dispositions that shape the researcher and their approach to research. From Robbins:

“We know from Bourdieu’s later articulation of a reflexive methodology, involving conscious ‘epistemological breaks’, that he was as dissatisfied with an ethnomethodological approach that might suppose that phenomena could absolutely speak for themselves as he was with the detachment of structuralist objectivity. As a method of enquiry, Bourdieu’s ‘post-structuralism’ sought to integrate both aspirations, but it was also always the case that he saw his texts as products generated within a system of communication where meaning is constructed reciprocally in the way in which he had outlined in ‘Champ intellectuel et projet créateur’” (Robbins, 2007)

One important intellectual resource for Bourdieu in this formidable task was the work of Gaston Bachelard, French philosopher of knowledge and science during the early 20th century, who was referenced earlier. Bachelard’s non-positivist epistemological approach was starkly different from French sociologists at the time and it enabled Bourdieu to begin to imagine what a non-positivist, reflexive sociological epistemology could look like. For Bachelard, “scientific knowledge is ‘constructed’ and ‘dialectical’ knowledge, one that does not arrive at final truths but proceeds as an ongoing project of correction and rectification of past errors” (Swartz, 1997, 31). Sociolanalysis requires reflexivity, because knowledge must be communicated and legitimated in language and we are embedded in concrete social relations that produces that language.

Similar to Bachelard, Karl Mannheim presented Bourdieu with more theoretical resources for a non-positivist epistemology of science. For Mannheim, the sociology of knowledge (or Wissenssoziologie) attempts to analyze the relations between symbolic forms of knowledge and objective social structures. The idea of socially bounded knowledge implies a set of necessary assumptions: meaning/knowledge is organized according to certain structures, these structures take on “symbolic forms,” and that these symbolic forms are more often than not delineated by socio-economic or class membership (Kögler, 1997). Mannheim states: “Different social strata, then, do not ‘produce different systems of ideas’ {Weltanschauungen) in a crude, materialist sense—they ‘ produce ‘ them, rather, in a sense that social groups emerging within the social process are always in a position to project new directions of that ‘intentionality’, that vital tension, which accompanies all life” (Mannheim, 1921/1922).

Another resource for Bourdieu in developing notions of reflexive epistemology in the social sciences was the work of another anti-positivist, neo-Kantian: Georg Simmel. Simmel worked to develop a formal sociology defined by relations. For Simmel, all of social reality came from the form of social interactions, the content of these interactions, and the reciprocal influence that these interactions would have on individuals over time. For Simmel, one could not understand social phenomena without first beginning with small-scale interactions and the micro-level structural shape/form that they took (Simmel, 1895). Taken together, Bachelard, Mannheim, and Simmel describe neo-Kantian notions of the phenomenological alongside non-positivist, reflexive approaches to the sociological study of science. These thinkers paved the way and enabled Bourdieu to formulate a truly innovative way of generating situated knowledge about the social world that was thoroughly scientific while also relational with respect to the subjects and the researcher alike.

Unified Praxeology: Reflexivity of the Researcher + Relational Methodology

Bourdieu’s synthetic ontology—which collapsed old antimonies—set up the possibility of a truly reflexive epistemology: a way in which knowledge could be generated without resorting to positivistic, macro-level studies using statistical controls or falling back to philosophical hand-waving about the state of nature. Rigid theoreticism and methodologicism can now be done away with and a total science of the social can now be advanced. Agnostic to any one particular method, Bourdieu was freed to pursue modes of inquiry, data collection methods, and tools of analysis that fit the question at hand—both practically and philosophically.

This meant that a well-trained scientific habitus would need to be developed: social scientists need to think relationally, particularly while constructing their object of study (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992, 224-235). As would be assumed from a reflexive epistemology, there can be no separation between empirical “technical” choices and “theoretical” choices in the construction of the object of study. There must be unity between the hypotheses given by the existing literature, the theoretical presuppositions given by the existing evidence, and the theoretical-methodological choices made in trying to gather and interpret data / evidence about the given social phenomenon. What’s more, the positionality and relationship of the researcher to constructed object of interest must also be carefully taken in to account. Bourdieu explains:

“To construct a scientific object also demands that you take up an active and systematic posture vis-a-bis ‘facts.’ To break with empiricist passivity, which does little more than ratify the preconstructions of commons sense, without relapsing into the vacuous discourse of grand ‘theorizing,’ require not that you put forth grand and empty theoretical constructs but that you tackle a very concrete empirical case with the purpose of building a model (which need not take a mathematical or abstract form in order to be rigorous.)… Ordinary sociology, which bypasses the radical questioning of its own operations and of its own instruments of thinking, and which would no doubt consider such a reflexive intention the relic of a philosophic mentality, and thus a survival from a prescientific age, is thoroughly suffused with the object it claims to know, and which it cannot really know, because it does not know itself.” (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992, 236).

These epistemological breaks more often than not correspond to social breaks: with decorum, methodological purity, political norms, and group definitions. This is how Bourdieu has chosen to advance such a radically politically subversive social science agenda. Rather than serving as the total “public intellectual” a la Sartre or the completely politically dispassionate, positivistic social scientist such as Levi-Strauss, Bourdieu demonstrates the depth of symbolic power that the scholar can wield. By documenting the concrete relationships between actors in a field of practice, displaying the types and relative inequalities in ownership of different species of capital by those actors, and watching, over time, as those actors demonstrate dominance or submission in relationship to one another, a praxeological socio-analyst can uncover social realities previously obscured. Perhaps more importantly, by exposing these previously hidden social realities of dominance and submission, new modes of political action and activism are made thinkable and therefor possible.

Conclusion: Bourdieu as a way up and out?

I will conclude with an assessment of if and how Bourdieu’s work creates the opportunity for a truly liberating social theoretical approach. Does Bourdieu’s repackaging of classical ideas into a reflexive and relational sociology give us a “way out” of the colonial-epistemological bind?

As I discussed in the introduction, social theory is rooted in an ontology and has developed an epistemological approach that made imperialism understandable and justified. Auguste Comte first used the term “sociology” in 1839 to characterize “the social” distinct from political, economic, and religious realms. In practice though, it was a way of creating a new technical domain of elite social scientific researcher. Privileged classes have been able to use the technical understanding produced through sociology to manage threats to social order from below their ranks. As Julian Go describes, classical social theory could be looked at in juxtaposition to postcolonial thought, which is fundamentally anti-imperial and grew out of English and literature departments at the beginning of the 1980s. Writers such as Edward Said, Gayatri Spivak, and Homi Bhabha; historians including Ranajit Guha or Dipesh Chakrabarty; and anti-colonial theorists Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire, Amilcar Cabral, W. E. B. Du Bois, and C. L. R. James were central to these efforts. These writers, and others, sought to articulate a worldview and cultural analysis that rejected the humanist/positivist way of knowing the world. (Go, 2016).

Taking a Bourdieusian approach, we might ask: in what systems of relations were classical social theorists embedded? What types of risks and rewards—material and symbolic—were at stake in their lives and their work? Similarly, we might ask the same questions of the subaltern, southern-positioned, and post-colonial thinkers. What concrete sets of embedded relationships, forms of symbolic and material capital, and lived dispositions form the matrix of their decision-making and practice? Though I have not done this analysis, I can imagine the value. And, for me, this is why I would answer the fourth question I laid out in the introduction affirmatively. Using a relational, reflexive, Bourdieusian approach, we can actually approach these questions in systematic and rigorous way. Through constructing these questions as empirical objects of praxeological socioanalysis, we could imagine generating new knowledge about the situated nature of the production of knowledge, and to the power processes embedded within and reified by the network of actors responsible.

Bourdieu’s epistemological approach, alongside a pragmatic praxeological sociolanalysis, does in fact give us the theoretical leverage to overcome the colonial roots and symbolically violent forces of historically constructed classical social theory. Bourdieu’s work does not, however, give us answers. It does give us an alternative social scientific language necessary to ask different types of empirical questions. These empirical questions, when paired with a relational methodology and reflexive epistemology have the potential to split apart the deep structure of power and privilege to enable serious analysis. Whether or not this is a truly liberating approach will have to do with the courage and skill of the sociologists who attempt to deploy it. While it may be true that “the past of social science is always one of the main obstacles to social science,” Bourdieu’s work can help us to imagine a future social science that is at once more synthetic, unified, and critical.

Works Cited

Bourdieu, P., Wacquant, L., & Farage, S. (1994). Rethinking the State: Genesis and

Structure of the Bureaucratic Field. Sociological Theory, 12(1), 1–18. http://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818312000033

Bourdieu, Pierre. (1993). Sociology in Question. London: Sage.

Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. J. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bourdieu, P., Harker, R. K., Mahar, C., & Wilkes, C. (1990). An Introduction to the work of Pierre Bourdieu: The practice of theory. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Brubaker, R. (1985). Rethinking Classical Theory: The Sociological Vision of Pierre

Bourdieu. Theory and Society, 14(6), 745–775.

Bruun, H. H. (2008). Objectivity, Value Spheres, and “Inherent Laws.” Philosophy of the

Social Sciences, 38(1), 97–120. http://doi.org/10.1177/0048393107311144

Comte, A. (1896). The positive philosophy.

Durkheim, E., & Fields, K. E. (1995). The elementary forms of religious life. New York: Free Press.

Durkheim, E. (1951). Suicide, a study in sociology. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

Edmunds, J., & Turner, B. S. (2005). Global generations: Social change in the twentieth century. British Journal of Sociology, 56(4), 559–577. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2005.00083.x

Gherardi, S. (2009). Practice? It’s a Matter of Taste! Management Learning, 40(5), 535 http://doi.org/10.1177/1350507609340812

Go, J. (2016). Postcolonial thought and social theory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Goldberg, C. A. (2013). Struggle and solidarity: Civic republican elements in Pierre Bourdieu’s political sociology. Theory and Society, 42(4), 369–394. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-013-9194-z

Kelley, D. P. (2005). Intellectual History in a Global Age. Journal of the History of Ideas, 66(2), 41–70.

Kögler, H. H. (1997). Alienation as epistemological source: Reflexivity and social background after Mannheim and Bourdieu. Social Epistemology, 11(2), 141–164. http://doi.org/10.1080/02691729708578839

Montesquieu, C. D. (1949). The spirit of the laws. New York: Hafner Pub. Co.

Mannheim, K. ‘On the interpretation of Weltanschauung’ (1921/1922), in Mannheim, K., Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 196

Marx, K., & McLellan, D. (2000). Karl Marx: selected writings. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Peters, G. (2012). The Social as Heaven and Hell: Pierre Bourdieu’s Philosophical Anthropology. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 42(1), 63–86. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.2011.00477.x

Riley, D. (2015). The New Durkheim: Bourdieu and the State. Critical Historical Studies, (Fall), 261–279.

Robbins, D. (2003). Durkheim Through the Eyes of Bourdieu. Durkheimian Studies, 9(1), 23–39. http://doi.org/10.3167/136202403780788777

Robbins, D. (2007). Sociology as Reflexive Science: On Bourdieu’s Project. Theory, Culture & Society, 24(5), 77–98. http://doi.org/10.1177/0263276407081284

Shipman, A. (2004). Lauding the Leisure Class: Symbolic Content and Conspicuous Consumption. Review of Social Economy, 62(3), 277–289. http://doi.org/10.1080/0034676042000253909

Simmel, G. (1895). The problem of sociology. Philadelphia: American Academy of Political and Social Science.

Simon, R. M. (2011). Habitus and Utopia in Science: Bourdieu, Mannheim, and the Role of Specialties in the Scientific Field. Studies in Sociology of Science, 2(1), 22–36. http://doi.org/10.3968/j.sss.1923018420110201.004

Swartz, D. (1997). Culture & power: The sociology of Pierre Bourdieu. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Trigg, A. B. (2001). Veblen, Bourdieu, and Conspicuous Consumption. Journal of Economic Issues, 35(1), 99–115. http://doi.org/10.2307/4227638

Wacquant, L. (2013). Bourdieu 1993: A Case Study in Scientific Consecration. Sociology, 47(1), 15–29. http://doi.org/10.1177/0038038512472588

Here’s some exciting, positive news: colleagues at BU and I are launching a campaign to unionize graduate student workers at Boston University with the

Here’s some exciting, positive news: colleagues at BU and I are launching a campaign to unionize graduate student workers at Boston University with the