Background

The World Development Report in 1993 focused on the economic value in focusing on a narrow set of health interventions.

On the 20th anniversary of the highly influential 1993 World Development Report, titled ‘Investing in Health’, an independent commission convened by The Lancet has developed a potentially groundbreaking report (Global Health 2035: a world converging within a generation) summarizing the current research demonstrating the potential economic value of universal health coverage, and lays out an aggressive but fairly straightforward set of policy recommendations that could help ministers of health, civil society, and advocacy organizations push forward legislation and regulation necessary to secure the right to health.

I think that this report is very significant for a few reasons:

- The commission is a mix of the right players (Harvard academics and administrators, ministers of health, USAID, World Bank, IMF, etc).

- It is fairly critical of the failings of the 1993 WDR. And, it offers sound analysis and recommendations about how to build off of the successes, failures, and lessons gained during the tumultuous decades in global health and development since then.

- It seems to have Partners In Health’s strategy and logic all over it. From the almost explicit ‘preferential option for the poor’ language to the model of structure and function for emerging health systems, PIH has certainly influenced this important vision for the future.

- The report is coming at just the right moment. Twenty years after the ‘Investing In Health’ WDR and approaching the end of the era of the Millennium Development Goals, we sorely need a progressive, ambitious, and inspiring vision to guide us. As I’ve written previously and continue to witness/study, more students than ever are passionate about advancing the right to health. Our work with PIH | Engage shows that people of many ages and demographics are eager to participate as well.

Major concepts in GH2035:

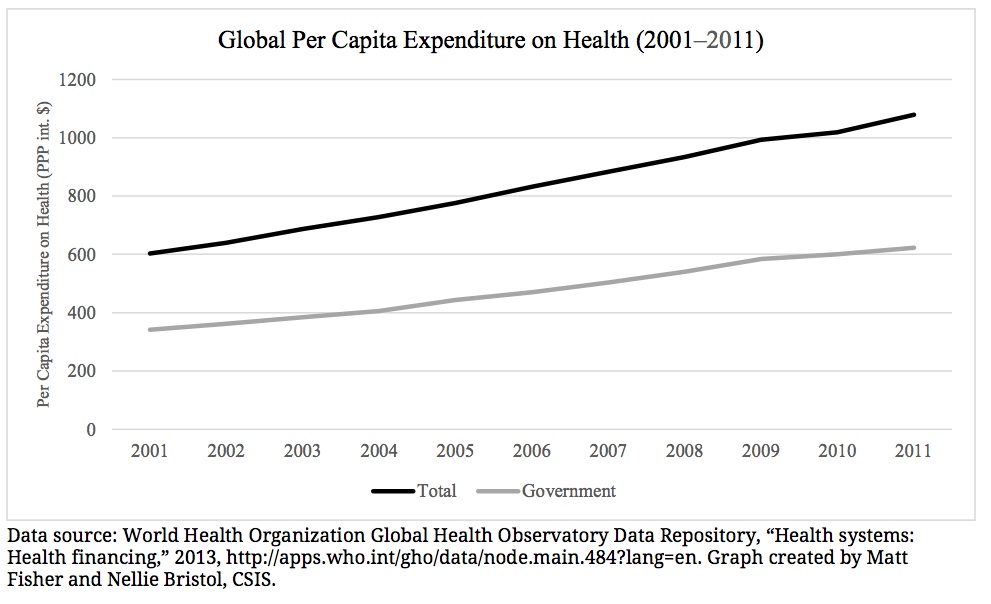

There is a major economic payoff in investing in global health.

How does investing in health effect personal and national income?

The report builds off of the work of the 1993 WDR in making the case that investing in health is not only a moral imperative – it is actually just that, an investment in the productive capacity and “full income” of a country. By solely using GDP growth (only accounts the market value of goods and services produced in one year) as the metric of development success, a lot of important value is missed and policy is built and evaluated in an incomplete way.

“On re-reading WDR 1993, admittedly with the benefit of hindsight after two decades, we believe that it had two major limitations. First, although WDR 1993 discussed the “instrumental value” of better health (eg, better health improves worker productivity), it did not attempt to quantify the “intrinsic value” of health (the value of good health in and of itself). Our report summarises research that quantifies the intrinsic value of mortality reduction— the findings should, we hope, lead to a notable reassesment of the priority of health in national and international investment portfolios. In particular, benefit-to-cost assessments and a strong implementation record point to the value of increased commitment to health.

Second, financial protection failed to receive sufficient attention in WDR 1993, although very few data were available in 1993 about out-of-pocket spending and catastrophic financial expenditures. Moreover, only a few analyses pointed to financial protection as an important goal of health systems. By contrast, the role of UHC in providing financial protection is a major feature of our report.”

The analysis that they have gathered shows that fully 24% of “full income” growth in low income and middle income countries can be attributable to the “value of additional life-years” which is linked to expanded investments in health.

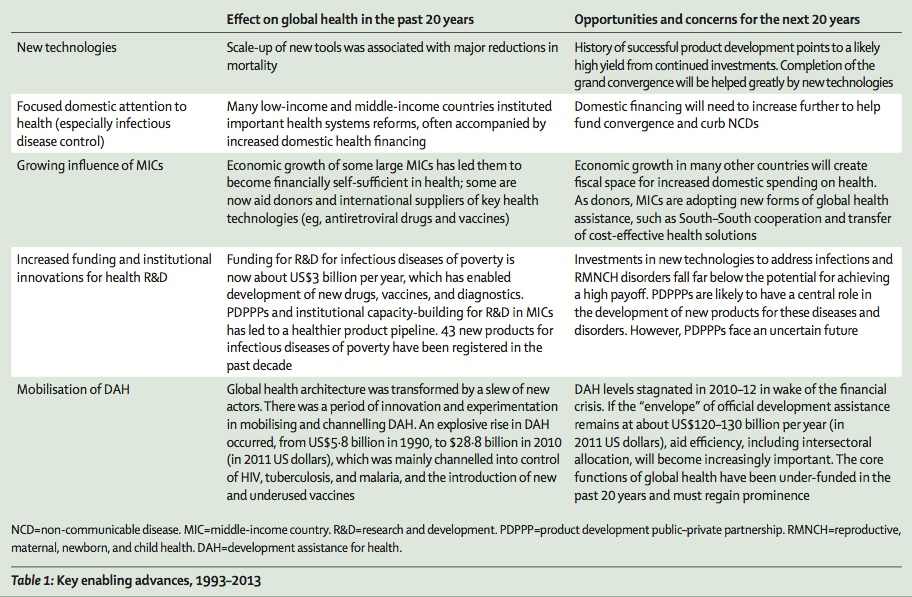

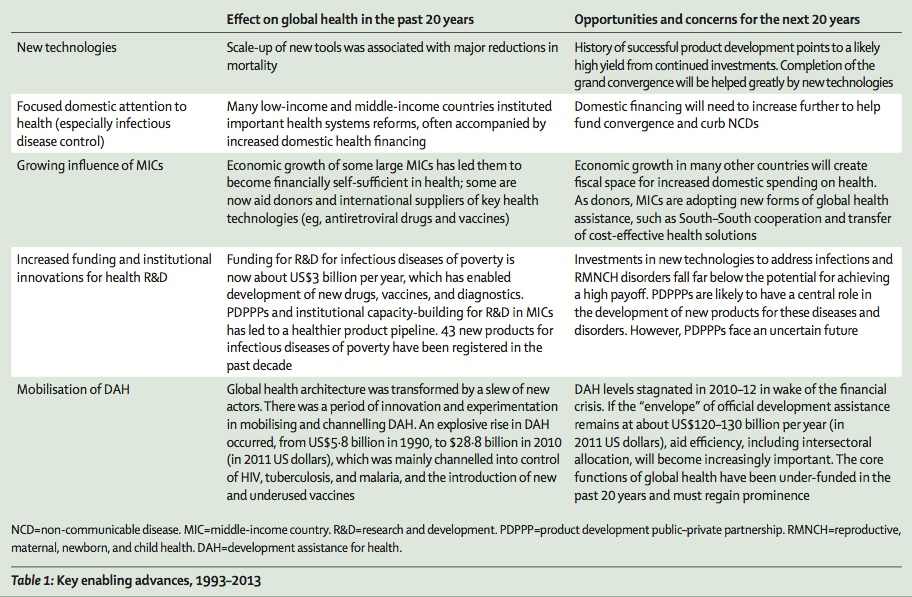

What’s happened in global health over the past 20 years that has led to such success? Well, they’ve kindly summarized their finding in a handy table:

A grand convergence of death rates from infectious disease, child, and maternal mortality between the high and low income countries.

With the right investments made by local governments, appropriate investment in health systems strengthening, renewed commitment to expanding development assistance for health from wealthy countries, we could see an incredible convergence of rates of infectious disease death, childhood death, and maternal mortality. The report builds the case that by 2035 we could see rich and poor countries alike experiencing very little unnecessary deaths from these completely preventable sources.

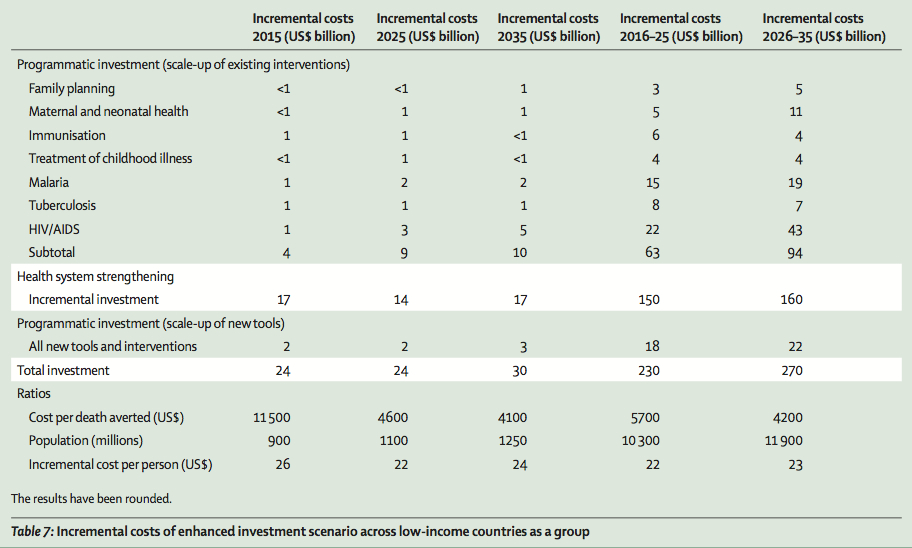

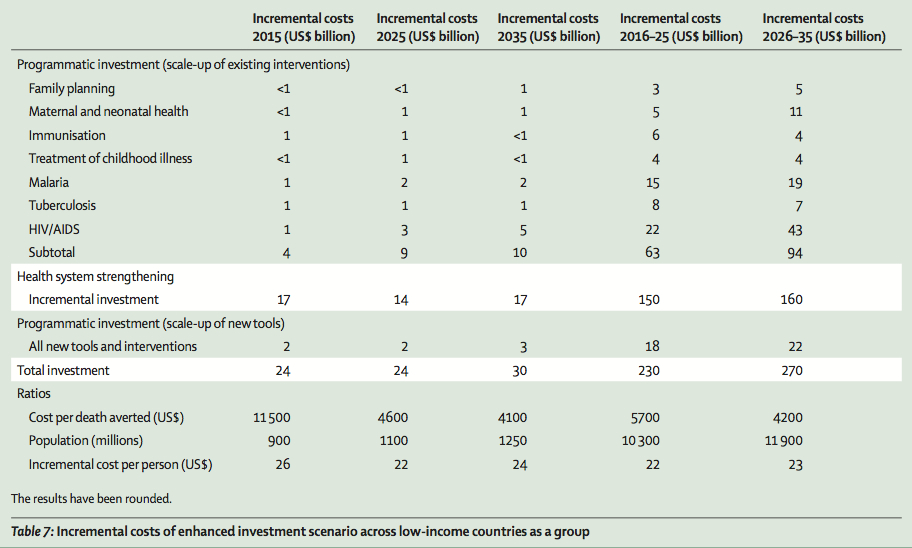

What kinds of investment are necessary? Well, the price tag over the next twenty years is not small – an aggressive investment scenario calls for at least $500 billion to be invested between 2016 and 2035 in low income countries’ health systems. Here’s the breakdown:

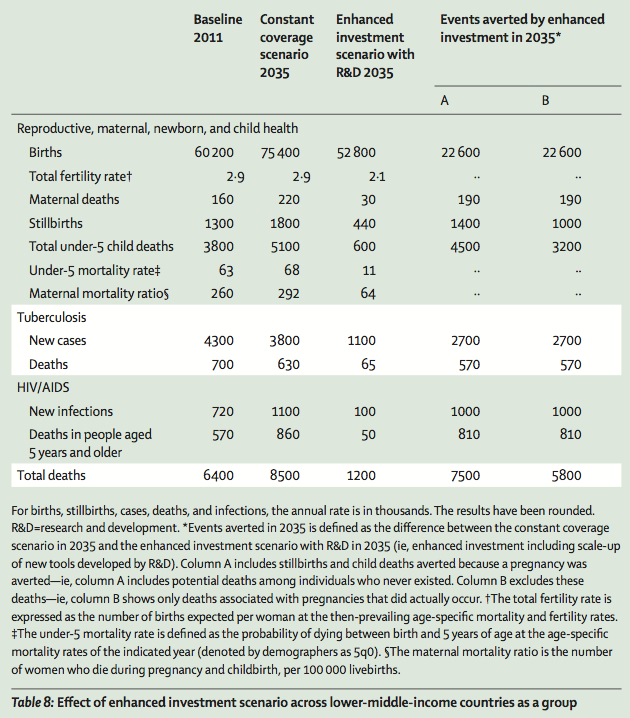

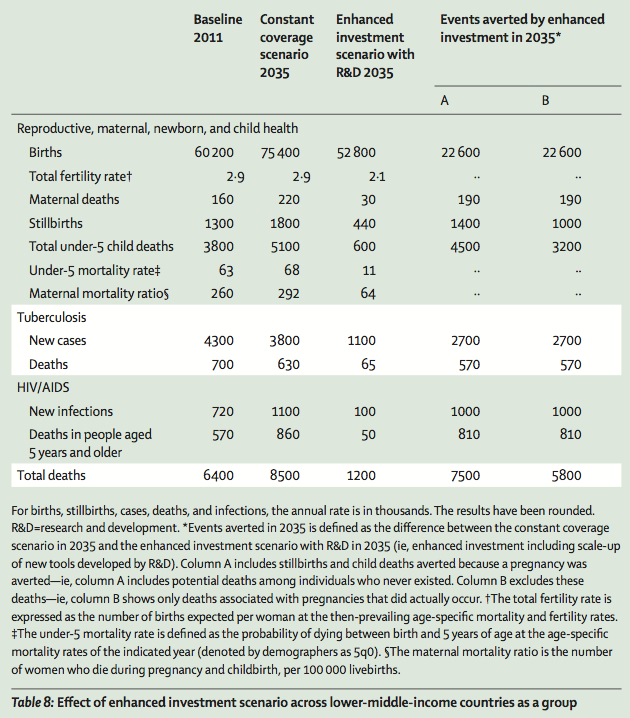

But what types of health outcomes could you conceivably see as a result of that type of aggressive investment in health? Perhaps as many as 7.5 million lives saved across low income countries during that time period:

Fiscal policies (taxation, regulation, etc) are a major lever in controlling non-communicable diseases.

The report advocates for aggressive use of fiscal policies as levers to combat what will be rapidly growing rates of chronic and non-communicable diseases, especially in low income countries. These polices include but aren’t limited to heavily taxing tobacco and other harmful substances as well as reducing subsidies on fossil fuels.

“Progressive universalism” is the most efficient way of achieving financial protection for health programs.

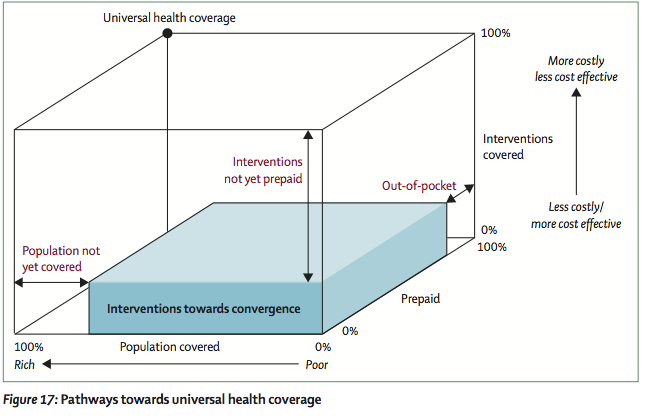

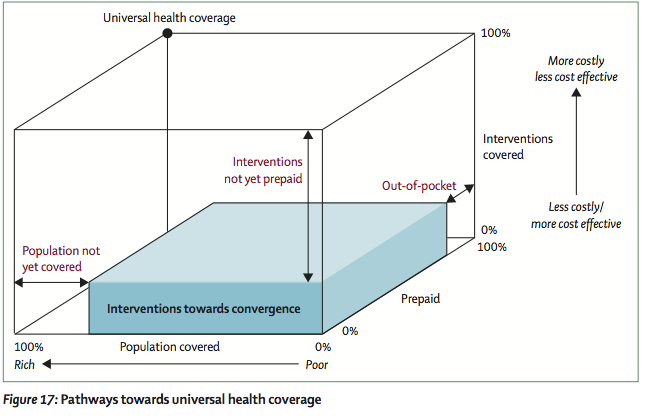

For me, the most striking focus of this report is the extraordinarily pro-poor focus on achieving universal health coverage through two potential pathways that they describe as “progressive universalism.” They conceptualize the process to move toward universal health coverage using the “universal health coverage cube – a way of understanding the trade-offs and choices policy makers must make along the way.

The cube consists of three dimensions: the percentage of the population covered, the percentage of costs pre-paid at the point of service (the rest paid for out of pocket), and the percentage of interventions that are covered by prepaid schemes.

Essentially, if a system has no one covered, none of the real costs associated with clinical interventions are pre-paid, and no interventions are covered through pre-paid schemes, that’s bad and does not approach UHC. You’re in a system that is in the bottom, right, front corner of the cube. Conversely, if people within a health system have all of their costs pre-paid at the point of service, all possible services are covered within the pre-paid scheme, and everyone within a population is covered, then you’ve got universal health coverage.

The report outlines two ways of “moving through the cube.” The first, and ideal strategy, would be to create a publicly financed health insurance system that would cover essential health interventions for entire populations. Basically, using “x, y, and z” coordinates imposed on the cube above, it would mean a large x (population covered) and a large z value (percentage of costs prepaid vs out of pocket), but a relatively small y (percent of all interventions that are covered through the system).

The second feasible strategy would be to provide a larger benefit package, financed through a mix of public and personal resources, from which the poor would be exempt. Basically, a smaller x value, similar z value, and a larger y value.

Potential implications for advocacy strategy?

I’m personally most interested in this report because I think that it provides a viable “stake in the ground” around which nonprofit organizations, civil society, advocacy networks, and ministries of health can mobilize and direct collective effort. It presents an ambitious vision for what could be. It provides the beginnings of a roadmap for how we could plausibly build upon the successes and challenges of the last 20 years in global health and actually make headway in recasting health expenditure from being considered sunk costs to be minimized, and moving towards a commitment of robust investment. And, just maybe, we can even move past the idea of investment and consider health a fundamental human right to be protected as a central component of modern citizenship.

This is, of course, where politics and advocacy come in. Some questions emerge:

- What types of organizations and grassroots campaigns are necessary in high-income countries to create the political space necessary to create the necessary development assistance for health funding streams necessary to see a plan like this enacted?

- What types of organizations and campaigns are necessary in low-income countries to hold their governments and elected officials accountable for adequate public sector investment in health?

- What type of advocacy is necessary to bring the lessons and innovations from low income countries working to pioneer UHC to high income countries, in order to disrupt dysfunctional health systems with massive politically and economically entrenched interests?