I first heard of PIH | Engage from a listserv email, sent out to alumni of the study abroad program I participated in. Not knowing quite what to think, but already in love with the global health nonprofit Partners In Health, I emailed this mysterious Jon Shaffer with a few questions. Instead of the standard written reply sent a few days later, and in what I would come to know as typical Jon fashion, he immediately responded with “wanna hop on the phone?”

And so started my plunge into community organizing. As I would soon find out, PIH | Engage was a completely new initiative of Partners In Health, looking to build communities of volunteer organizers across the United States. These teams of 10 or so people would work to 1. Raise funds for the lifesaving work of Partners In Health, 2. Advocate for policies that enable governments to build functioning health systems, and 3. Create a space for discussion of the global health issues marginalized populations face every day. Jon would sometimes refer to PIH | Engage as an “experiment,” aimed at harnessing the inspirational power of PIH’s brand and engaging dedicated supporters in the movement for global health equity. With the recent explosion of global health departments and student groups on university campuses, the biggest engagement gap seemed to be for recent graduates, who may have studied these issues in college but found it too difficult to find well-paying jobs in global health after graduating.

For me, a passionate supporter of PIH’s work and a public health student/soon-to-be young professional with limited opportunities for direct involvement in global health work, PIH | Engage seemed perfect. I applied to be a Community Coordinator.

Like all fledgling community organizing initiatives, PIH | Engage’s pilot year had its ups and downs. Movement-building is hard work, I found, and takes serious commitment. But I ended the year excited and hopeful for the initiative’s future—already, communities (including my own) had been built across the U.S., and PIH | Engage had brought together more than one hundred dedicated volunteers. After graduation, I was determined to stay involved with this experiment that I had come to truly believe in. After a summer spent volunteering at the PIH Boston office, I jumped at the opportunity to apply as the Community Organizing Assistant and work to build PIH | Engage full time.

An illustration of PIH | Engage’s growth: Year 1 Training Institute, in the conference room of PIH & Year 2 Training Institute, with more than 60 Community Coordinators, coaches, and volunteers.

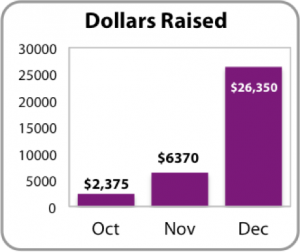

Now, a few months later, PIH | Engage has made tremendous progress. We have about 40 strong communities and more than 300 members, who together have raised close to $40,000, advocated for continued U.S. support of the Global Fund, and began the “PIH | Educate” curriculum based on Dr. Paul Farmer et. al.’s excellent new textbook, Reimagining Global Health. Each month, I’m on the phone with each Community Coordinator, sharing best practices, discussing struggles, and coaching them through the campaign.

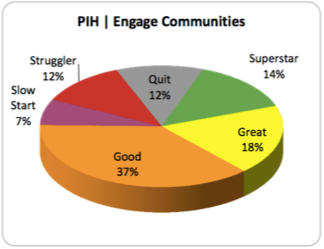

I recently undertook a thorough assessment to more systematically calculate each community’s “strength,” based on a series of metrics such as the size of their leadership teams, participation in the campaign, and events held. The results of this report were promising:

- 69% of communities ranked in the “superstar,” “great,” or “good” category for strength

- 88% of communities have held a first monthly meeting; 79% have held several meetings

- 67% have held their first event

- Leadership teams have an average of 6 members, and 74% participated in the personal fundraising campaign

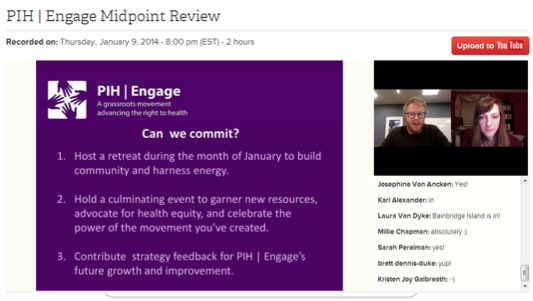

Through this analysis, I was able to see more clearly what structural elements of a community led to it’s success and what barriers most often caused a community to struggle. Jon and I will use this report to target our coaching and support of PIH | Engage teams in the coming months, and reflect on ways we can better recruit and plan for next year, Year 3 of PIH | Engage. As the first step, we hosted a Midpoint Review video-conferencing webinar with our entire network last week, to reflect on our progress so far and re-launch into our spring campaign.

As much as PIH | Engage is an experiment in community organizing, my journey from Community Coordinator to Community Organizing Assistant has been a wonderful and rewarding career experiment. It’s been incredible to be a part of this initiative, and see our movement grow. I can’t wait to continue to share our progress, successes, and challenges. Onward!

—

By Sheena Wood

Sheena works as the Community Organizing Assistant at Partners In Health. A recent graduate from Brown University, she enjoys reading about community organizing and global health, traveling, and eating dark chocolate.