As I have studied equity-oriented global health delivery, it’s become increasingly clear that the concerted effort to define liberty / freedom as equivalent to and inseparable from completely unregulated “free markets” is central to understand the contest at the center of a movement for the right to health. We learned last week from Dr. Salmaan Keshavjee and his book, “Blind Spot: How Neoliberalism Infiltrated Global Health” that a handful of intellectuals gathered after WWII to mount a concerted social strategy to “win the battle of ideas” in the global forum; to fight and reverse the notion of the welfare state, New Deal policies, the specter of Communism, and social and economic rights. The Mont Perelin Society set forth a radical intellectual, but also political, social, and moral project to reshape the foundation of Western liberal thought and underpinnings of the relationship between citizen and state.

In the wake of the Iowa caucuses last night it’s important to reflect on the historical roots of neoliberalism and the legitimate social movement that is driving the modern Republican party further and further to the radical right. In the recent New Yorker article, New Koch: The billionaire brothers are championing criminal-justice reform, Jane Mayer chronicles the work of the Koch brothers, their sprawling political network, and their recent re-branding effort. Once again we see a clash of ideas and a serious social / political strategy to decouple citizens and states and move forward the radical aim of completely unfettered markets.

Of specific interest to me was an article she cites from Harvard sociologists Theda Skocpol and Alexander Hertel-Fernandez: The Koch Effect: The Impact of a Cadre-Led Network on American Politics. In it they present an in-depth analysis of the evolution, organizational components, and effects that Koch-inspired and funded organizational network has had in driving polarization and shifting the GOP rightward over the past decade+. As opposed to just looking at the funding of political campaigns, ads, think tank and policy work, they take an organizational approach to try to understand the constellation of organizations, individuals/roles/positions, and institutional effects that these organizations have had on the two traditional political parties. As they put it:

“The Koch network is not just a congeries of big money donations from the two brothers themselves, or a loose, undisciplined array of advocacy groups and political action committees to which the principals send checks. Instead, the network has by now evolved into a nationally federated, full-service, ideologically focused parallel to the Republican Party. The Koch network operates on the scale of a national U.S. political party, pledging to spend in the 2016 cycle more than twice what the Republican national committee spent in the previous presidential election and employing more than three times as many staffers as the Republican committees had on their payrolls as of late 2015 (Vogel 2015a; Bump 2014)…

In a disciplined way, the Koch network operates as a force field to the right of the Republican Party, exerting a strong gravitational pull on many GOP candidates and officeholders.” 1

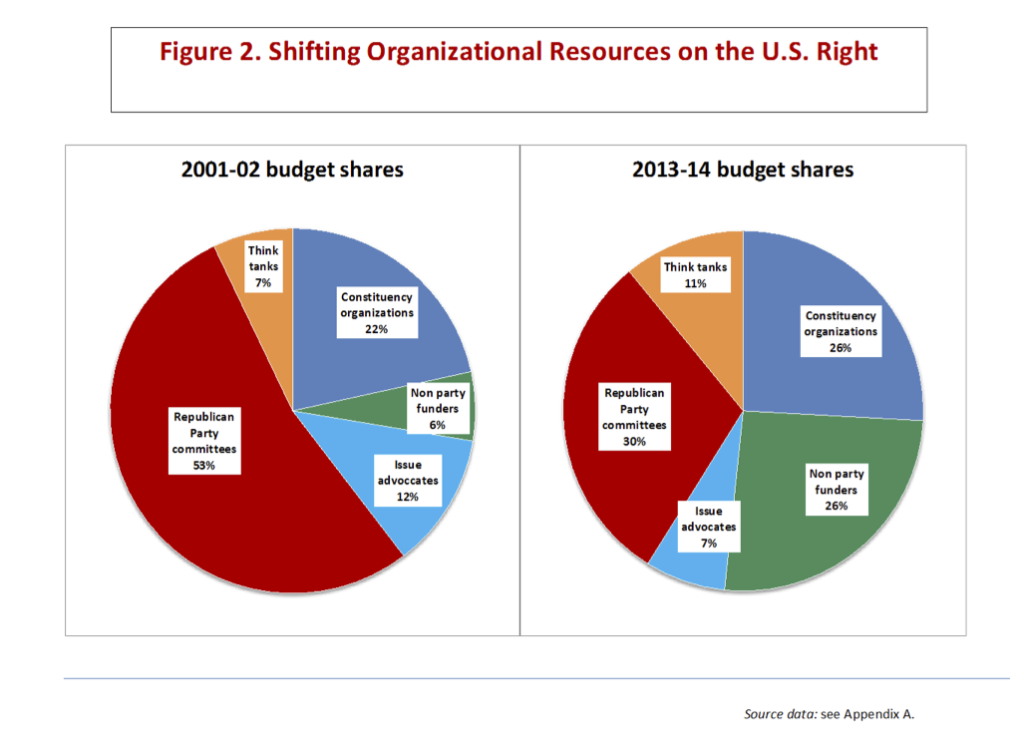

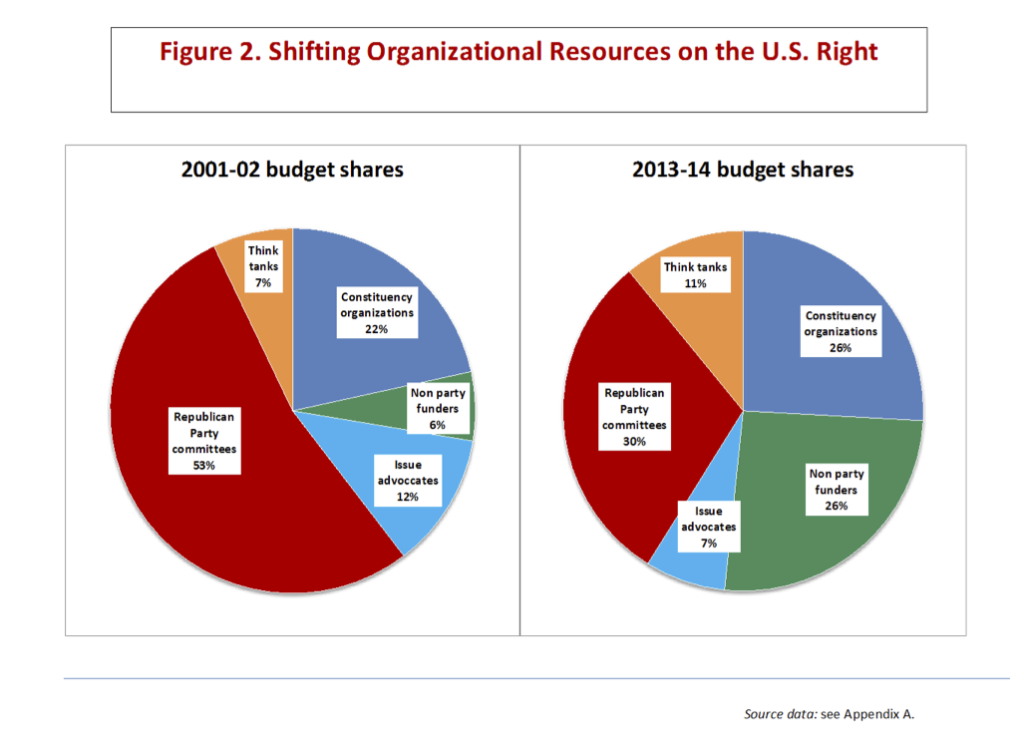

They demonstrate that the fraction of resources controlled by the formal GOP party committees has dropped significantly over the past 10 years, and so has the power of these institutionalized political party channels.

Skocpol and Hertel-Fernandez show a striking drop in resources controlled by the GOP party committees.

They also make the argument that the Koch brothers’ funding and institutional network touch all five of the most important types of political organizations that contribute to and influence party politics:

- Political party committees: formal RNC / DNC

- Non-party funders: organized groups of donors that fund campaigns and political activities

- Constituency organizations: mobilize mass bases of people (think NRA / labor unions)

- Issue advocacy organizations: pro-life / pro-choice groups, anti-tax groups, etc

- Think tanks: produce policy research and concepts, like Heritage, Cato, Economic Policy Institute, etc

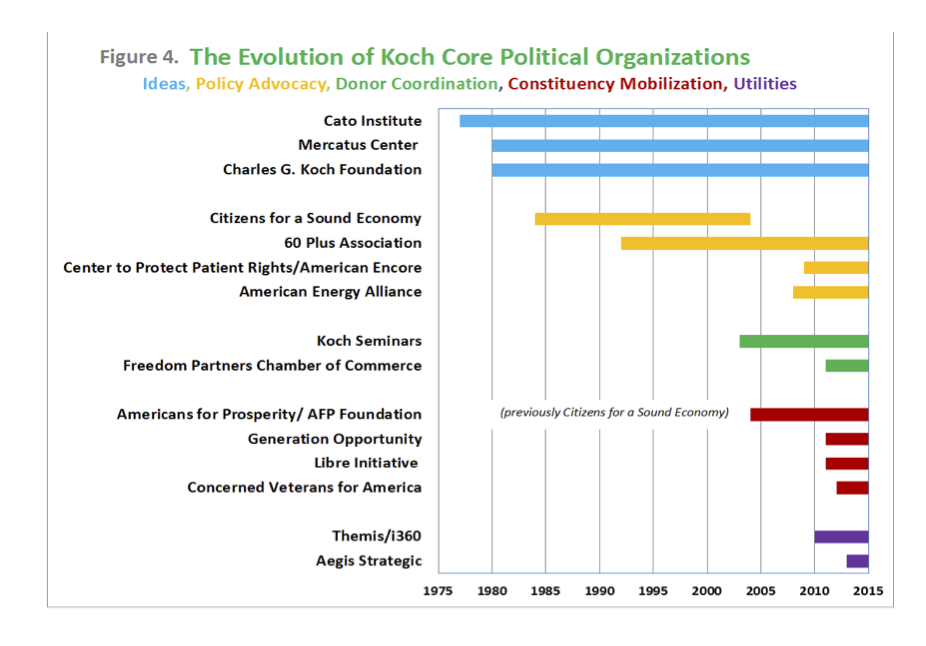

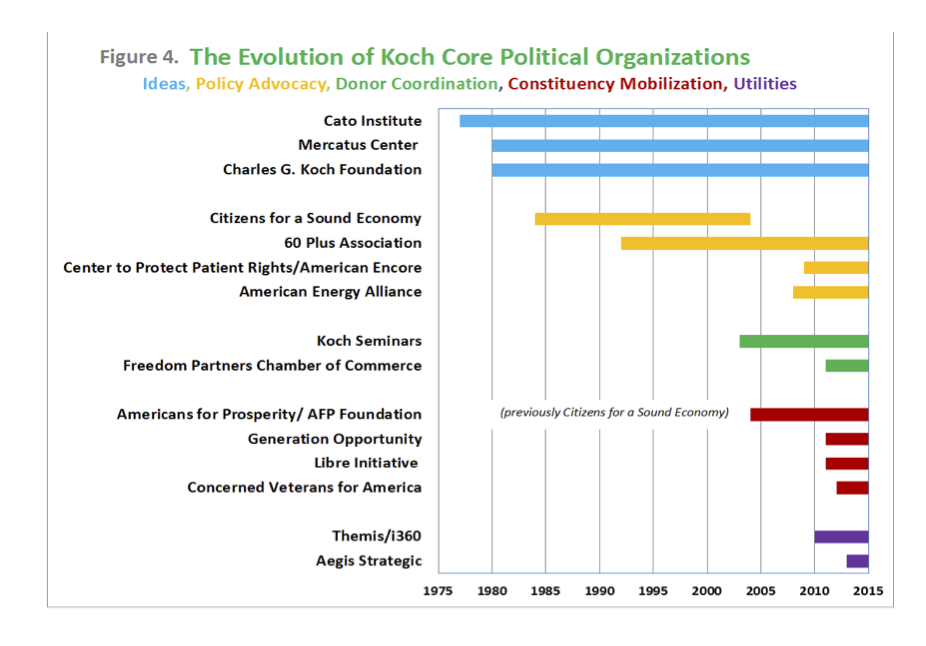

Since 1975, the Koch brothers have catalyzed the creation and coordination of organizations that contribute to each of those key areas of party politics. At the root of this strategy is that:

“the Kochs take ideas seriously and believe that politicians “reflect” rather than create “the prevalent ideology” (see Schulman 2014: 99). The Kochs were major backers of the nation’s leading libertarian think tank, the Cato Institute, founded in 1977. Starting soon after, in 1980, they began continuous sponsorship of the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, which runs educational programs in the humanities as well as policy studies and, these days, regularly issues research and policy recommendations on major issues such as global warming. Finally, perhaps the most prominent of several family foundations is the Charles G. Koch Foundation, which regularly disburses hundreds of grants to college and university-based scholars and programs, all meant to encourage free market and libertarian ideas and policy proposals (Levinthal 2015; Schulman 2014, 264- 66).”

The Koch’s creation of political organizations spanning idea creators, policy advocacy, donor coordination, constituency mobilization, utilities.

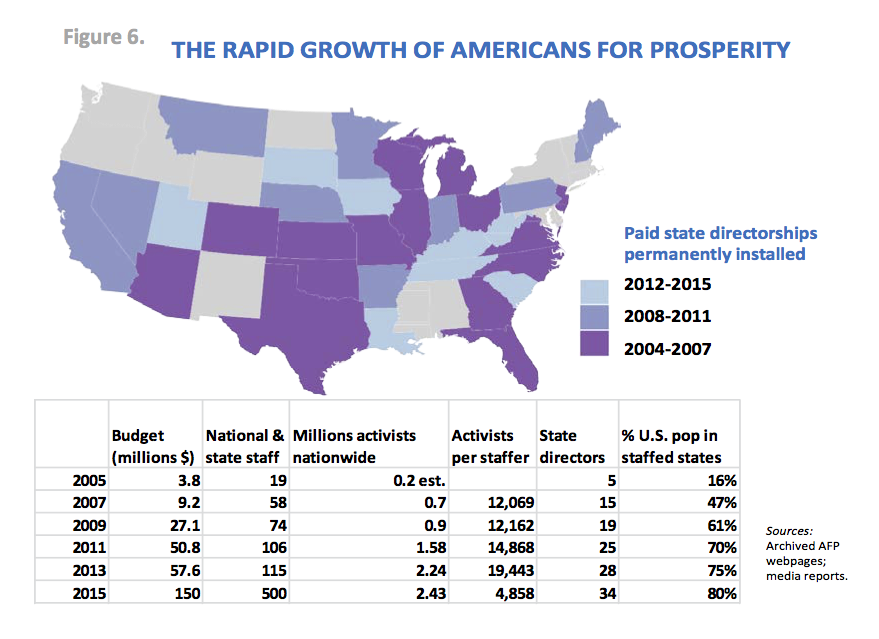

Especially striking is the more recent strategic investment in a rapidly growing grassroots constituency network of mobilizing organizations.

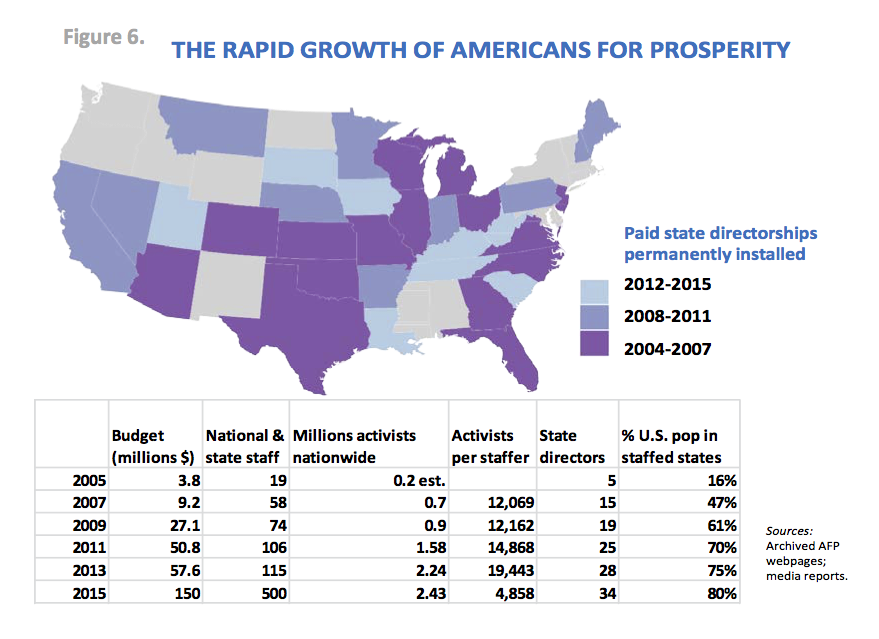

Growth of the Koch funded and coordinated grassroots network of activists.

“But even though AFP is highly centralized like a corporation, it also has a federated structure with important state-level organizations, just like classic American voluntary associations and the U.S. governmental system as a whole (Skocpol et al. 2000). Directors and other paid staff members such as “grassroots directors” are installed in most of the states and given considerable room to monitor and influence state and local politics and weigh in locally with their state’s U.S. Senators and Representatives.

State-level AFP organizations are called “chapters,” but that is a misnomer because they are not really in any sense controlled from within the states themselves. Although AFP usually appoints directors who have experience and longstanding ties in their states, these pivotal players are not elected by in-state activists or selected through any internal decision-making process.”

Going back to Bourdieu, McAdam, and Ganz as useful theoretical underpinnings in understanding social movements, its difficult to dismiss that their description of the Koch’s sprawling political institutional network that links formal political party committees, non-party private funders, constituency/grassroots organizations, issue/policy advocacy organizations, and policy-creating think-tanks seems very Bourdieusian. It looks like an incredibly sophisticated strategy to not only play the electoral game of American politics, but a much more ambitious attempt to grow the political, social, symbolic, financial, and even cultural capital with the aim of re-writing the rules of American political game: one in which the state functionally ceases to exist.

McAdam’s political process model is also a useful analytical tool here: Hertel-Fernandez and Skocpol have identified the grassroots organizational strength of this network, shown the emerging political opportunities that the network is tapping into, demonstrated the effect of “cognitive liberation” created by think tanks and policy scholarship networks. Looking at broader political and economic trends–growing inequality, rising polarization and distrust of traditional political parties, the maintenance of Citizens United and unlimited private spending on political engagement– its hard to see how this movement might be challenged and stopped.

The victory of Ted Cruz over Donald Trump is one very practical indicator of this success. Trump, racist and deplorable as he is, is not an ideologue, but Cruz is. Ted Cruz is the kind of litmus-tested neoliberal candidate the Koch machine is designed to elect.

The American left, let alone a global movement for social and economic rights and the right to health, has nothing this robust. If Bourdieu calls for the irreplaceable role of the collective intellectual, “by helping to create the social conditions for the collective production of realist utopias… organize or orchestrate joint research on new forms of political action, on new ways of mobilizing and making mobilized people work together, on new ways of elaborating projects and bringing them to fruition”, 2 why is the right winning?

- Skocpol, Theda, Hertel-Fernandez, Alexander. “The Koch Effect: The Impact of a Cadre-Led Network on American Politics” Inequality Mini-Conference, Southern Political Science Association. Jan. 28, 2016. ↩

- Bourdieu, Pierre. “A Scholarship with Committment.” Revueagone Agone 23 (2000): 205-11. Web. ↩