1) Introduction

Existing literature describes academic citation networks and the structure of knowledge fields: their diverse patterns, clustering, fragmentation, structural cohesiveness, and the link between micro and macro level processes in emerging domains of scientific knowledge production (Small & Griffith, 1974; Hill & Carley, 1999; Gondal, 2011; Daipha, 2001). However, little has been written to describe the specific structural changes over time of citation networks. How do certain nodes emerge and become central or structurally important over time? How and why do other nodes, important early in the citation network’s evolution, become far less important as the network matures? What are the macro and micro level processes that describe and govern this behavior and what social, epistemological, and political lessons can we draw from these changes?

These questions are important for growing our theoretical understanding of evolving scientific domains of knowledge. Practically, these questions are also important to explore the biopolitical dimensions of evolving hegemonic scientific domains and the constraints they place on practitioners making use of domains of scientific knowledge. A central notion in the sociology of health and medicine is the social construction of illness. Sickness, disease, and health problems are simultaneously materially located biological phenomena and a socially created meaning making processes through which normalcy and deviance get defined and play out in socially relevant displays of power and inequality. Some illnesses are particularly embedded with cultural meaning, others are socially constructed at the individual level–based on how individuals come to understand and live with their illness. Others are especially shaped by technical medical and scientific knowledge and are not necessarily given by nature but are primarily constructed and developed by claims-makers and interested parties (Conrad & Barker, 2010).

Additionally, the process of medicalization—the tendency to inscribe more and more social problems to be within the professional domain of medicine—continues to be a dominant trend in society. By expanding the medical domain to ever more issues and social problems, the challenges and conflicts associated with naming and framing illness comes to the fore. Rather than a given biomedical fact, we have a set of understandings, relationships, and actions that are shaped by diverse kinds of knowledge, experience, and power relations, and that are constantly in flux. This social constructionist perspective looks at how the phenomenon was identified and acted upon. Diagnosis is a matter of the “politics of definitions” (Brown, 1995).

Though medical sociology has given great attention to the complexities and power-processes associated with naming, diagnosing, and building systems to care for diseases at the population level, less attention has been paid to the ways that the structure of academic literature, and the citation networks that represent them, contributes to the processes of naming, framing and governing of illness. This paper looks at the structural evolution of the academic literature that deals with the intersection of noncommunicable diseases and “global health.” Historically and currently, both the terms “global health” and “noncommunicable diseases” (hereafter, NCDs) have been hotly contested (Airhihenbuwa et al., 2014; Whyte, 2012; Fassin, 2012; Beaglehole & Bonita, 2010). Both the broad and diffuse concept of “global health” and seemingly technical and clinically delimited field of noncommunicable diseases demonstrate the ways in which medical and scientific knowledge is socially constructed in complex ways (Keane, 1998; Brown, 1995; Lantz & Booth, 1998). The framing of NCDs in the global policy literature, in particular, has been a battle ground of biopolitics (Bukhman et al., 2015; Binagwaho et al., 2014; Katz, 2013; Mamudu et al., 2011).

Building off the current literature, I visually examine the changing structure of the global health / NCD academic literature citation network as well as quantitatively explore the changes in some of the macro-level characteristics of the citation network and their changes between 1995 and 2016. Additionally, using ERGM techniques, I also find evidence in support of important changes in the density and the emergence of a small number of structurally important paper / nodes in the network.

To conclude this paper, I will explore how structural changes in this citation network correspond with the content of the papers that dramatically change their structural position within the network. By linking this to a historical understanding of the changing framing of NCDs in the global policy making domain, I hope to make the argument that structural changes in the NCD/global health citation network shaped the framing for and contributed to limiting the political opportunities available to activists seeking to mobilize new resources for the growing NCD burden amongst low income populations globally.

2) Research Question

More concretely, I hope to answer the following questions: 1) How do the global characteristics of the NCD/ global health citation network change, qualitatively and quantitatively, between 1995 and 2016? 2) What were the most important micro-level structures that caused macro-level changes in the network over that time period? What historical, social, and political effects could these structural changes in the network both represent and perhaps be causing in the broader field of global health governance?

3) Data and Methods

Research focused upon the structure of knowledge production frequently relies on network data (Gondal, 2011). As Gondal describes,

“The nodes in the network may be researchers, documents, concepts, or organizations. The edges connecting these nodes correspondingly are collaborative authorship (Babchuk et al., 1999; Moody, 2004; Goyal et al., 2006), social and intellectual contacts between scientists (Lievrouw et al., 1987), co-occurrence of references in the bibliographies of other documents or co-citation (Small and Griffith, 1974; Moody and Light, 2006), shared citations of the same other documents or authors also known as bibliographic coupling (Kessler, 1963), sharedmem- bership in organizations (Cappell and Guterbock, 1992; Daipha, 2001), or conceptual similarity between documents (Small, 1978; Lievrouw et al., 1987; Hill and Carley, 1999). The analysis of such networks constructed from citation indices, organizational memberships, and authorships is largely conducted at two levels. At the dyadic level, researchers have been concerned with the meaning attributed to the edges interlinking the nodes. At the ‘global’ or ‘macro’ level, researchers analyze the topological properties of the network as a whole providing a bird’s-eye description of the research field. There is yet another level – the ‘local’ or ‘micro’ level – involving more than one tie but significantly less than the complete network which remains relatively under-analyzed in the literature.”

In this paper I attempt to show not only the birds eye view of how this citation network grows and evolves over time, but also how the micro-level structures that cause ties change evolve over time as well. I accomplished this by building a plain .txt citation data set from Web of Science (webofknowledge.com) querying the database and downloading all relevant citation and paper data for the papers meeting the search criteria. My criteria for this search were a) any of the diseases listed by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation as a “noncommunicable disease” (each with logical ‘or’), AND b) the term “global health”, c) between the dates of 1995 and 2016. I then used the CRAN “bibliometrics” package, downloaded to RStudio to transform this plain text data file into an adjacency matrix (see Appendix 1 for R code). From there, I was able to generate the annual graphs of the growing NCD / global health citation networks and their corresponding betweenness, closeness, and degree statistics. I additionally used the VOSViewer software for mac to further explore the structure and patterning qualitatively for the network. Finally, using the CRAN ERGM package in R, I ran ERGM models, testing for the log likelihood of the presence or absence of various important micro-level structures that may or may not be present in the given networks and may or may not change over time. Overall, this data set give me a useful view into both the micro and macro level structures and patterns within the global health / NCD citation network, but it also gives me good resolution as to how those network properties have changed over time.

4) Results

4.1 Global Properties of the Network

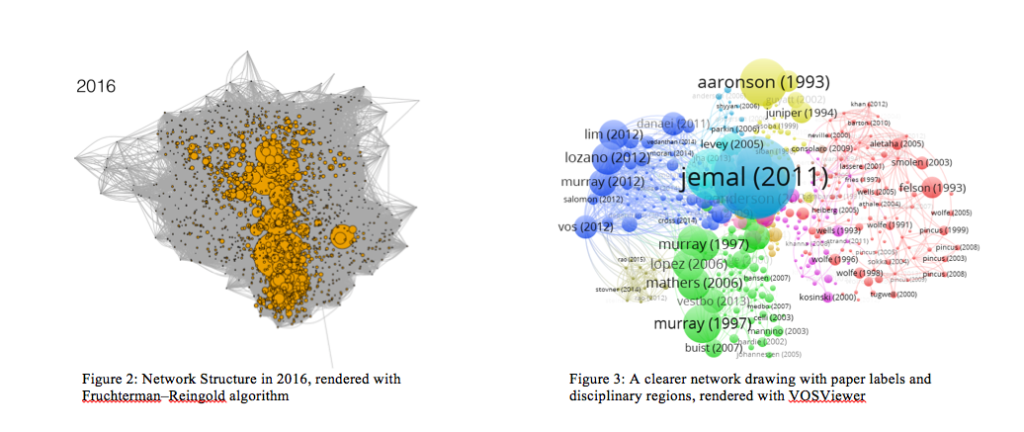

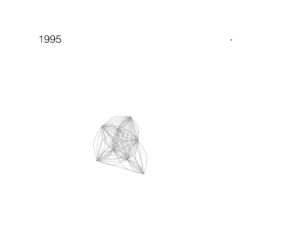

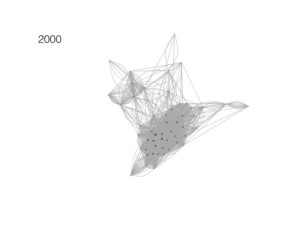

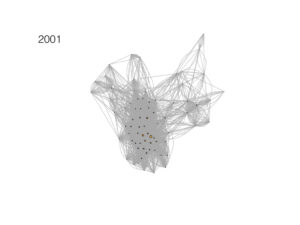

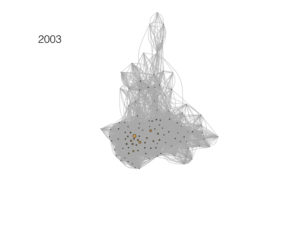

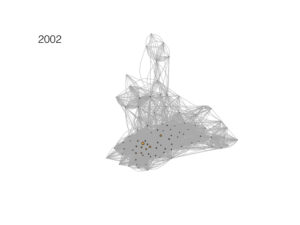

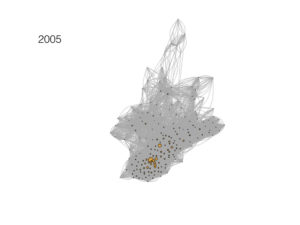

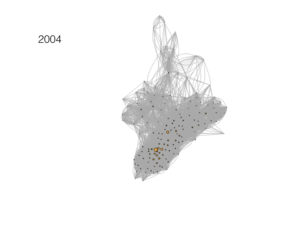

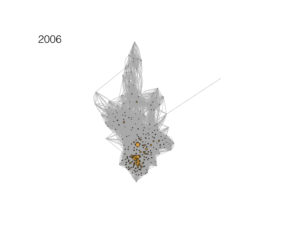

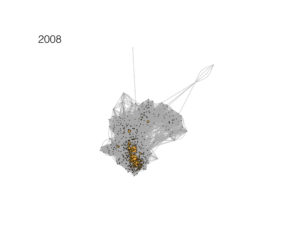

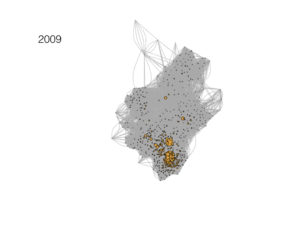

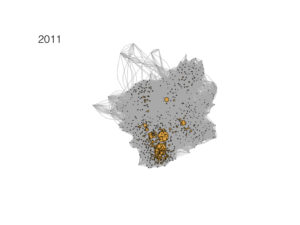

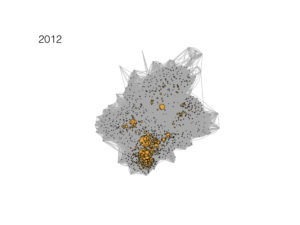

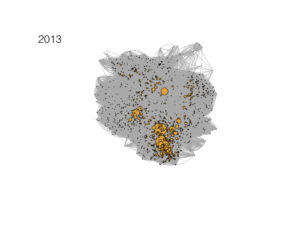

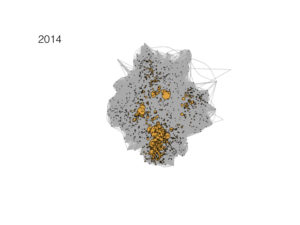

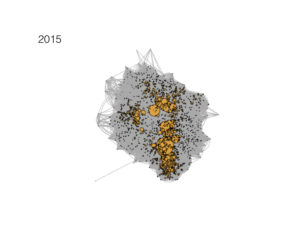

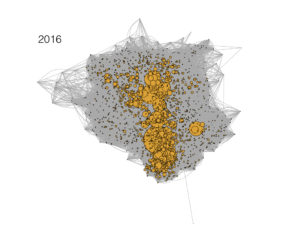

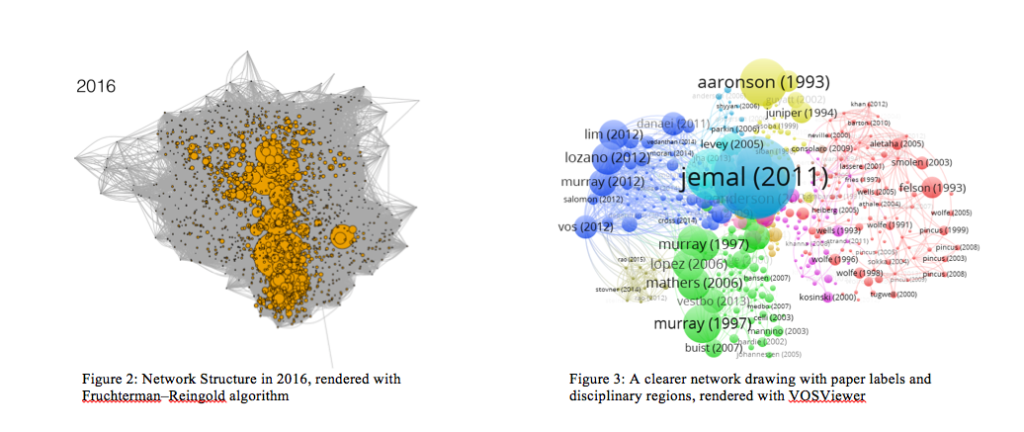

Figure 1 visually shows the evolving NCD / global health citation network over time, between 1995 and 2016. We see the network going from a mere handful of papers in 1995 to a seemingly very densely packed mess of papers, citations, and nodes in 2016. Nodes are slightly expanded based on their degree number (number of papers citing that paper) and so we see, starting in about 2001, the emergence of some “key nodes”—or papers that seem to be growing quickly in the number of citations that they are receiving from other papers in the network. Starting at about 2006, we see a significant density pattern towards the bottom of the network graph.These patterns are more easily visualized in the VOSViewer software. Using this visualization software, it is easy to see the breakdown of papers, the authors, their topics, and the conceptual/issue area/disciplinary clustering. Figure 3 shows the results of the visualization of the NCD / global health citation network in 2016 via the VOSViewer. Here we see that it has grouped the important nodes in the network into disciplines / areas of research based on the number of shared citations. The blue region represents papers concerned with global mental health issues. The green region represents pulmonary disease, heart disease, and epidemiological studies focused on lifestyle risk factors and population level public health intervention. The red region has to do with chronic pain issues, arthritis, and other rheumatic diseases. Finally, the yellow region represents papers that have to do with various forms of cancer. It is interesting to note that papers of similar topic and clinical area tend to group together.

Another interesting finding from this analysis was the see the rapid growth in importance of large scale epidemiological modeling and burden of disease measurement papers at the expense of more clinical/intervention focused papers. Specifically, the papers by Murray, Jemal, and Lozano are all large scale quantitative epidemiology papers aimed at measuring different components of the noncommunicable disease burden across the globe. This corresponds to some of the other the important findings in terms of changing structural importance within the network, which we I will discuss shortly.

4.2 The Changing Network Over Time

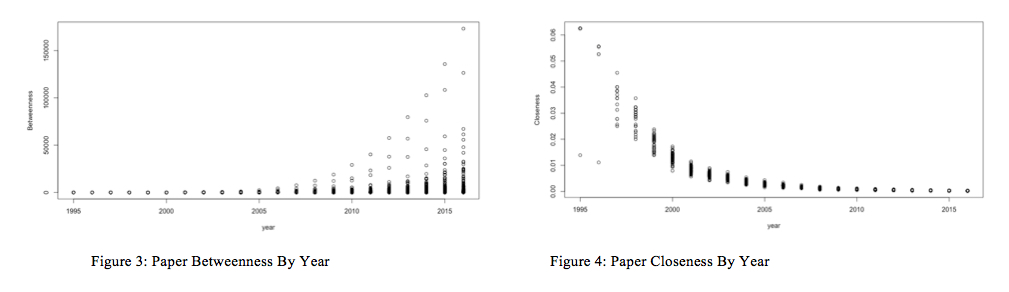

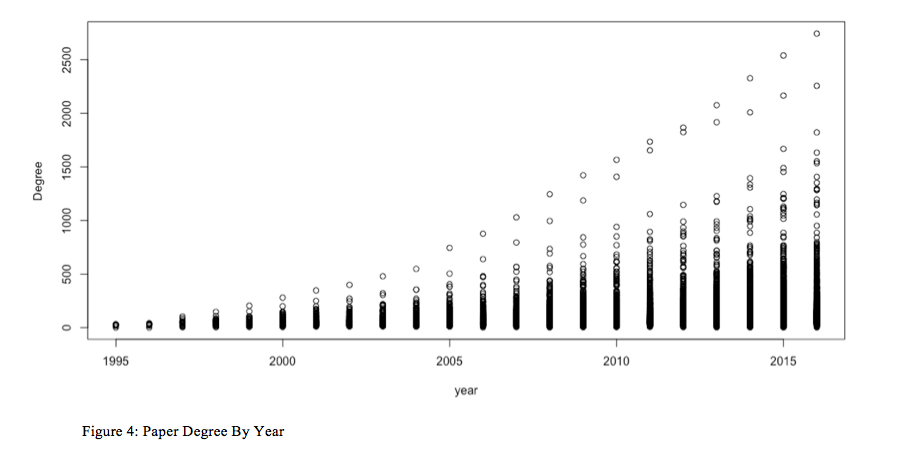

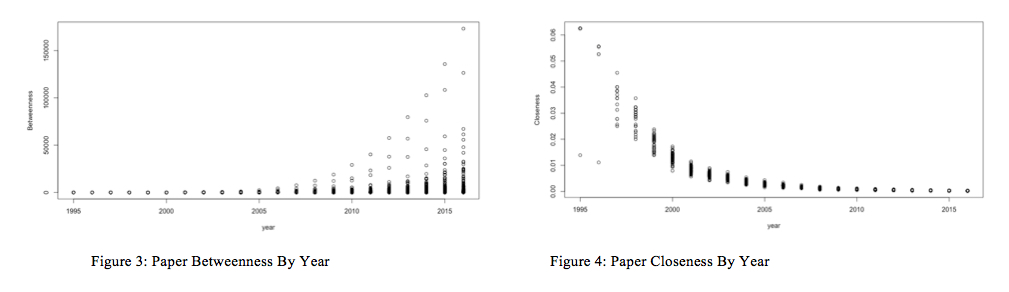

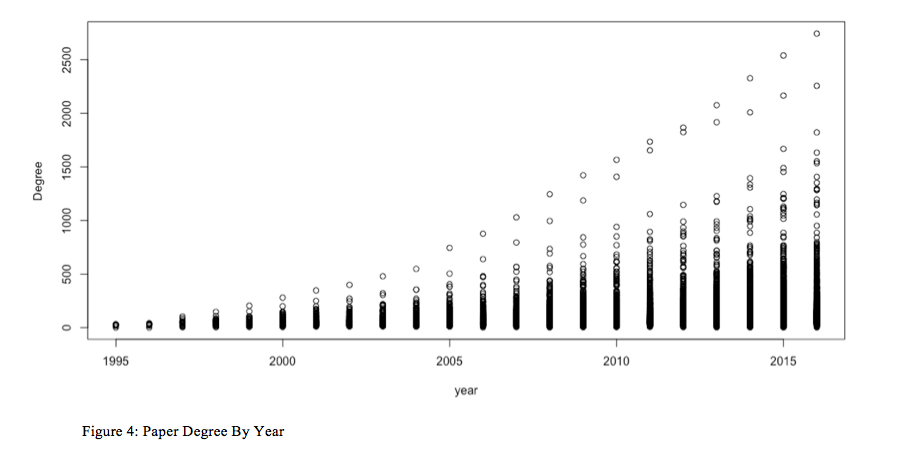

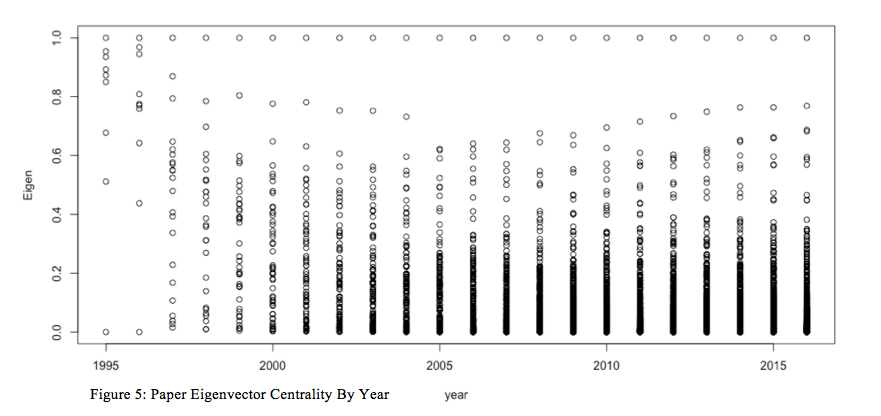

In addition to visually seeing the evolution of this citation network over time, I also wanted to explore some key network statistics—particularly different measures of centrality—of the papers in the network, and how those changed over the evolution and maturation of the citation network. Figures 3, 4, and 5 show all of the networks papers’ betweenness centrality, closeness centrality, and degree between 1995 and 2016. Betweenness centrality refers to the number of actors that must “pass through” a given node in order to reach other nodes. More technically, “if the geodesic between actors n2 and n3 is n2n1n4n3 — that is, the shortest path between these actors has to go “through” two other actors, n1 and n4 — then we could say that the two actors contained in the geodesic might have control over the interaction between n2 and n3” (Wasserman & Faust, 1994, p. 188). This “actor in the middle” has some degree of control over the graph, hence it is an important statistic to quantify. Closeness centrality focuses on how close an actor is to all the other actors in the set of actors. The idea is that an actor is central if it can quickly interact with all others (Wasserman & Faust, 1994, p. 183). Lastly, degree simply refers to the number of edges connected to a given node. In this case degree is equal to the number of papers citing a given paper in the network.

Viewing Figures 3, 4, and 5 together reveals an interesting and striking pattern. First, in Figure 3 we see betweenness centrality unfailingly, yet unequally increasing for all papers in the network. Figure 4 shows conversely that paper’s closeness centrality unfailingly decreases over the time period observed, but again at slightly different rates. Finally, Figure 4 shows that degree appears to go up for all papers in the network, again at dramatically different rates across this citation network.

These observations demonstrate an interesting conclusion for this network: that betweenness and closeness appear to be inversely related to one another over time as a citation network grows over time. Practically, what this means is that as papers continue to be added to the scientific network space of global health / NCD research, they are increasingly citing seminal papers and making connections with other, less cited papers in the network. This rapidly growing, but relatively sparsely connected network creates more and more betweenness for each paper—there are more steps through the networks through which to go and therefor each paper in those steps are between ever more papers. But, at the same time, papers are being added to the network at such a rapid rate (and papers can only cite so many other papers) that network is becoming increasingly less dense and therefor the closeness of the papers within the network shrinks dramatically, especially starting around 2000. Finally, it also makes sense that in general, the degree for papers in the network would grow consistently over the course of the evolution of this citation network. Papers, even those rarely cited, will only grow in their number of citations and won’t decrease.

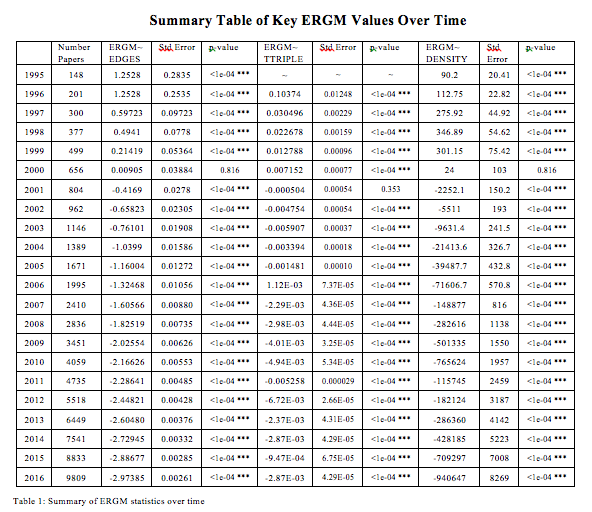

Table 1 (to be discussed more below) shows the number of papers in the network for each year: there is an almost exponential addition of new papers to the network starting around 2002. Given this explosion of new nodes being continually added to the network, the relatively few citations any one paper can have, it makes sense that closeness centrality would plummet over the course of the evolution of this network and that betweenness within the network would increase as the sparsely—yet still completely connected—network continues to grow.

4.3 Differential Eigen Centrality Trends

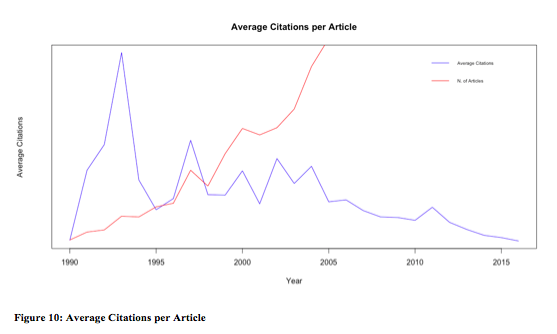

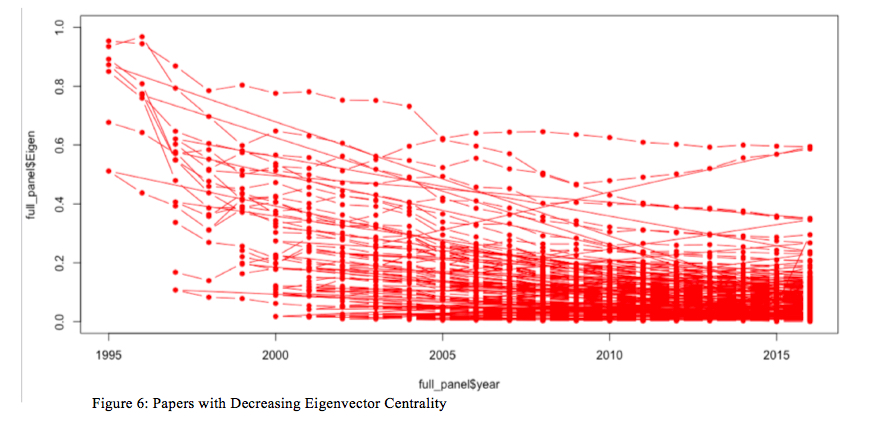

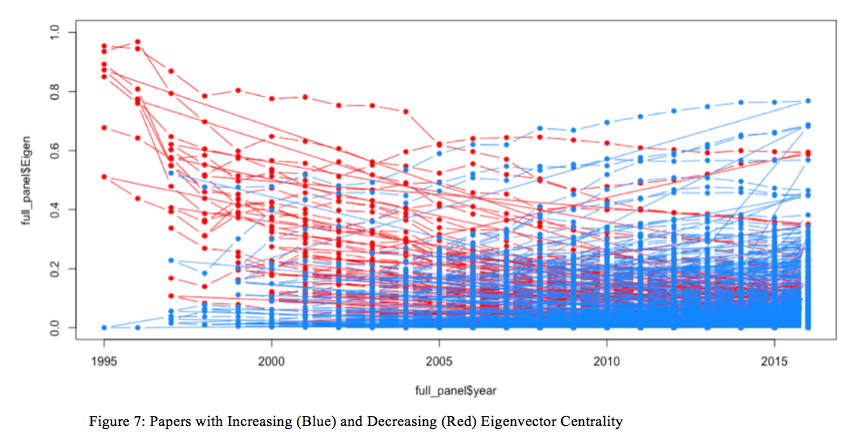

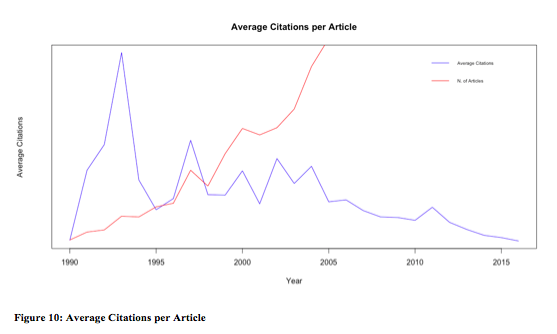

So, over time, the NCD / global health citation network seems to both be growing in terms of its overall size, the number of citations, and therefor its average betweenness of the papers in the network. Conversely, the network is becoming far more sparsely connected because of the sheer rate of addition of new papers and the limited numbers of citations that each paper can make (see Figure 10). What about the importance of particular papers? Are there specific papers (or groups) that seem to be becoming more or less important in the network despite the rapid expansion of the network itself?

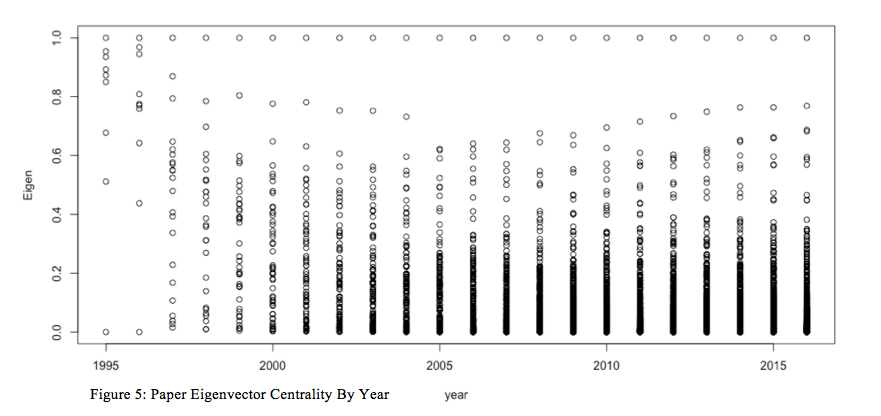

Eigenvector centrality is one such measure of importance or influence within a citation network. It assigns relative scores to all nodes in the network based on the number connections and quality of the scores of the connections a node has. The more important the node’s connections, the higher that node’s eigenvector centrality will be (Newman, 2014). We might hypothesize that similar to the betweenness measure, all papers would tend to become more important within the network over time. Or, conversely, perhaps, eigenvector centrality would tend to decrease rapidly with the rapid increase of the size of this citation network. Puzzlingly, neither seems to be the case: Figure 5 seems to show that some of the papers in this citation network are increasing in their eigenvector centrality score between 1995 and 2016, while other papers in the network decrease in terms of eigenvector centrality over this time period. How can we account for this?

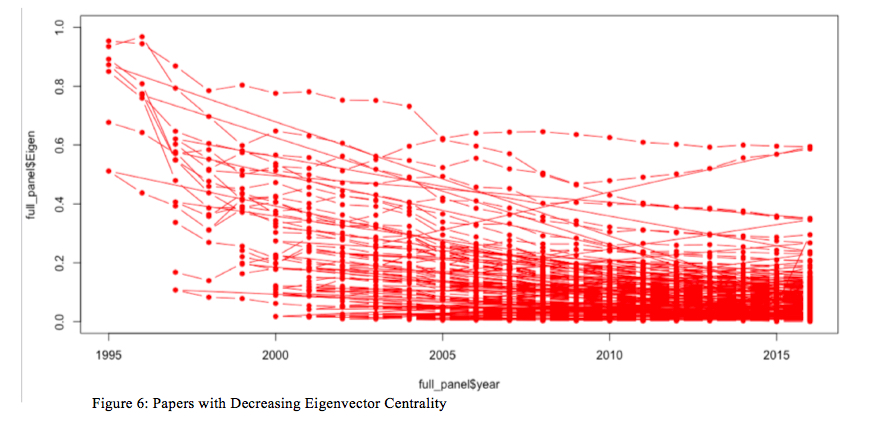

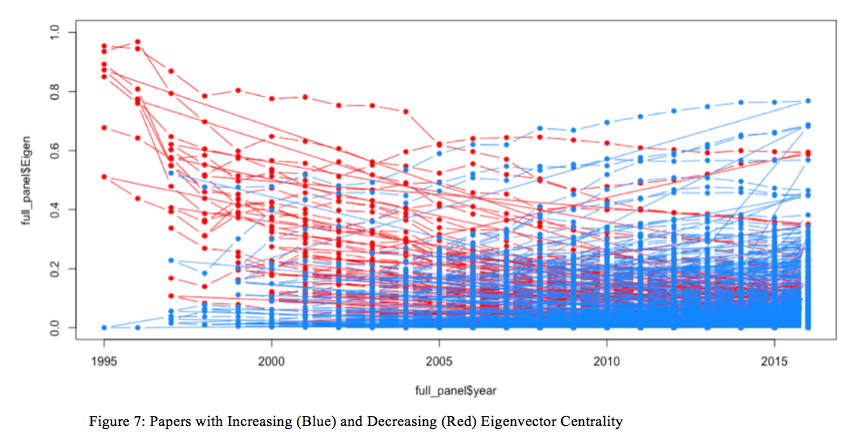

It seems that there is some pattern—some papers increase in eigenvector centrality while other papers decrease in eigenvector centrality—over the time period observed. But, what is the relationship between the papers that tend to increase or decrease in relative importance / influence in this network over time? To explore this, using R (see code in Appendix 1) we separated out the papers that had increasing eigenvector centralities and those with decreasing eigenvector centralities. Figures 6 and 7 show the plots of the increasing eigenvector centrality papers in red and the decreasing eigenvector centrality papers in blue. What unites these papers?

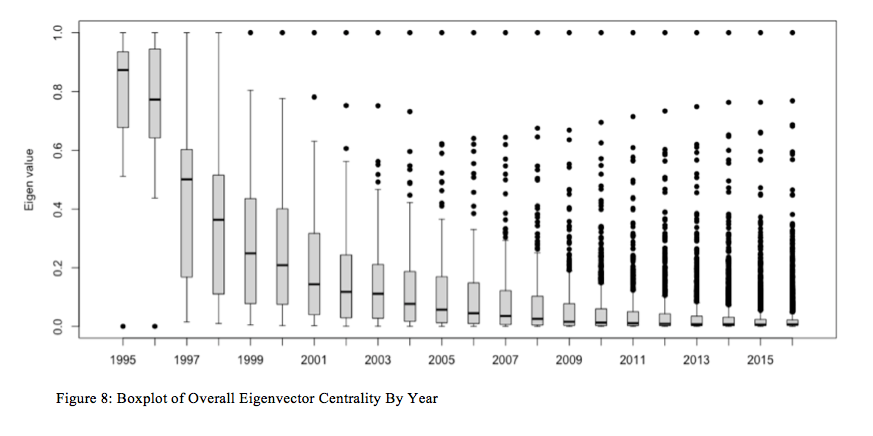

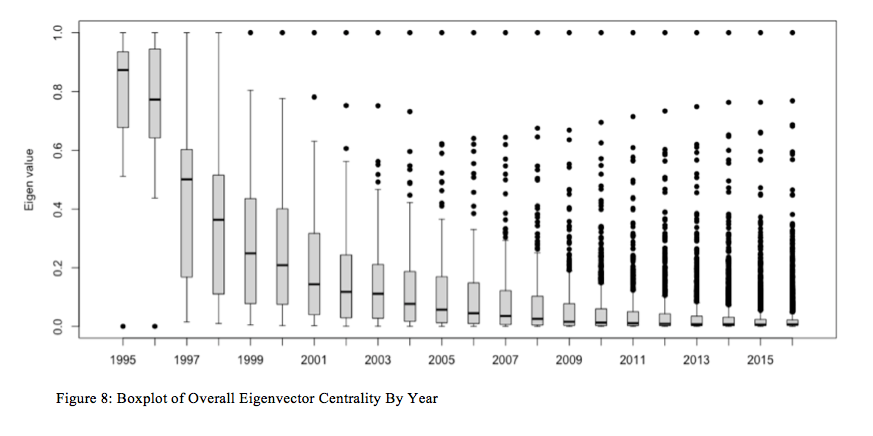

To gain a better understanding of the overall network trend of eigenvector centrality for the papers in question, I decided to create a boxplot of all of the paper eigenvector centralities for each year, which is represented in Fiugure 8. Figure 8, once again, shows a striking outcome: while there certainly are some papers that become far more important, structurally, over time within the network, the vast majority of the papers are virtually inconsequential as far as eigenvector centrality goes. For instance, in 1995, the average eigenvector centrality score was close to .9 with a modest standard error; by 2001, it was less than .2. As time progresses from 2001 through 2016, the average eigenvector centrality score crashes to nearly zero, while a handful of outliers grow in their structural importance within the network. Who wrote these papers and what were they about? Why and how have they become so structurally important within this network?

4.4 ERGM and the Analysis of Micro-Level Structure

One hypothesis may be that local, or micro-level structures could have an important role to play in the structural evolution of this citation network over time, thus causing certain papers/nodes within the network to have a structural advantage over the others as the field of knowledge production expands. Here I attempted a modest ERGM analysis (exponential random graph modeling). ERGM are a class of stochastic models which use network local structures to model the formation of network ties for a network with a fixed number of nodes (Wang et al., 2009). They are a useful method that uses Markov Chain Maximum Likelihood Estimation to approximate estimates for the odds ratio of the presence of different micro-level structures within a network.

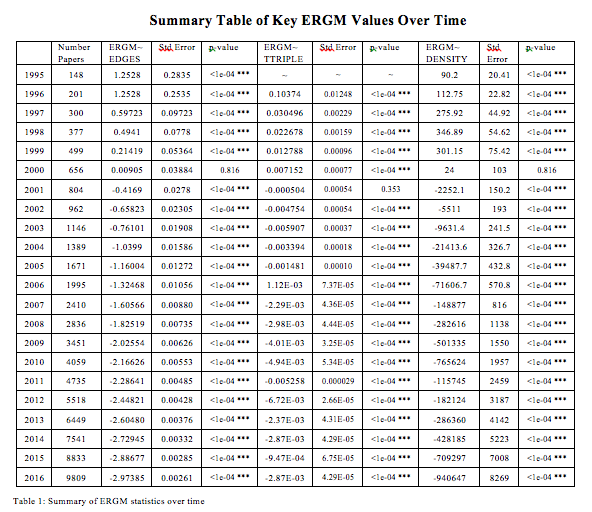

Table 1 shows the results of these modeling exercises on these NCD / global health citation networks as they evolve between 1995 and 2016. While running these models (which, it turns out, takes a ton of time and computing power) I learned that many of the network parameters that I had hoped to test within this network (such as k-star, 4 cycles, triangles, and triad census) would not produce MCMC models that would converge. So, I was not able to estimate those parameters.

However, I was able to estimate the ERGM parameters for the presence of edges, transitive triplets (ttriple), and density, and their values are found in Table 1. The column labled ERGM~EDGES can be interpreted as a log odds measure of the density of the network. As might have anticipated based on the analysis of betweenness and closeness, as well as the growth of the number of notes of the network, the log-odds of the probability of any tie (i.e. the density) crashes and starts to become negative starting in 2001. The column labeled ERGM~DENSITY demonstrate an analogues trend. The column labeled ERGM~TTRIPLE demonstrates a slightly different trend. It seems to start modestly low (I could not get the model to run for 1995 data, so it starts in 1996) and then seems to level out at approximate zero, not becoming more negative or positive as the network grows. This potentially represents the relative lack of importance of transitive triplets in the micro structure of this network.

Overall, I would be skeptical to make any grand claims about the utility of this ERGM analysis. Although my MCMLE models seemed to converge, I was not able to run goodness of fit analyses to test how well these estimates fit the model and my actual networks. Additionally, ideally, I would run these analyses on a faster computer or gain access to a university-based super computer since this is such a large data set and I am doing so many analyses with this time series panel data.

5) Discussion

One clear puzzle emerges from this analysis: while betweenness universally increases for this network and closeness universally decreases, eigenvector centrality climbs for some papers and crashes for others. What’s more, Figure 8’s boxplot overview of eigenvector centrality scores by year shows that, on average, the papers are inconsequential to the overall structure of the network and a handful of papers emerge to the top as by far the most dominant. What are these papers and what might it signify both for this as a domain of scientific knowledge and for the politics of global health priority setting?

Through analyzing the titles, abstracts, and authors of the papers that are most important in terms of eigenvector centrality and degree, ten papers emerge as centrally important:

- The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A Quality-of-Life Instrument for Use in International Clinical Trials in Oncology

- The MOS 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) 1. Conceptual Framework and Item Selection

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Source Information (1994)

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Source Information (2000)

- Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis

- Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010

- Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010

- Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences

- Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease Study

- A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010

There are several things that are remarkable about this list of the (by far) most important papers in this citation network. First, aside from the first most important paper—which is about the clinical process of diagnosing and treating cancer—none of these pieces are about a specific disease or even class of diseases. Instead, they are all meta-analyses or statistical overviews of epidemiological trends in noncommunicable diseases and their relative burdens globally. Second, the disease upon which they are focusing tends to be biased towards wealthy-world health issues: the DSM for mental health issues (which has a highly western-centric focus) and arthritis (has not been considered a ranking global health priority). Finally, all them have to do with capturing global measurements, standardized practices and protocols, and dominant paradigms—built from programs and practices rooted in the U.S. and Europe—that are to serve as models for health care systems in the global south. Considering that this network, examined from 1995 through 2016 was about “global health” and noncommunicable diseases, it seems surprising that these would be the overwhelmingly dominant papers in this sparsely connected network.

6) Conclusion

I began this paper with a commentary on the ways that scientific citation networks can enable and constrain the biopolitics of global health by reinforcing the legitimated framing of diseases and their interventions in certain ways, and not others. This paper points to the possibility that the structural evolution of the NCD / global health academic paper citation network has contributed significantly to this biopolitical conundrum. Specifically, important puzzle in the field of global health is: why have non-communicable and chronic diseases been so dramatically marginalized within the global health priority mix? First, comparing the burden of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) and infectious diseases to their relative magnitude of investment via development assistance for health (DAH) demonstrates a remarkable disparity. Despite accounting for more than 30% of the overall disease burden globally (especially in low and middle income countries), less than 1% of all DAH is allocated specifically to care, treatment, and prevention of noncommunicable disease (Daniels, Donilon, & Bollyky, 2014).

Second, there has been a concerted effort by the noncommunicable disease community of practitioners and scholars to raise the profile of NCDs on the global stage (Geneau et al., 2010). Much of this political and scientific labor has culminated in rare and highly important United Nations General Assembly High Level Meeting focused on the global burden of NCDs in 2011. This meeting was the first UNGA High Level Meeting on a health topic since HIV/AIDS in 2000. Yet, despite the attention from global leaders on the world stage, nearly no new resources have been committed and invested in global NCD care and management. Finally, central to this debate has been a question about the nature of the social construction of NCDs globally, especially with regards to the burden, causal sources, and necessary systems-level interventions to meet the burden. Leading up to the 2011 UNGA High Level Meeting on NCDs, the World Health Organization (WHO) has doubled down on a focused framework of limited shared “lifestyle modifiable” risk factors as the dominant causal source of the NCDs globally. Dubbed the “4×4 Framework”, the WHO has sought to limit the terms of debate and focus to what they deem to be the four most “important” NCDs and the corresponding individual level lifestyle modifiable risks: cancer, diabetes, cardio-vascular disease, and chronic respiratory disease; tobacco use, unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, and the harmful use of alcohol (WHO, 2013). Scholars and practitioners, especially those providing care in poor, remote regions of the world have taken aim at this framing, saying that it excludes much of the important burden of illness, especially amongst the very poor and rural populations around the world (Binagwaho, Muhimpundu, & Bukhman, 2014; Bukhman, Mocumbi, & Horton, 2015; Kwan et al., 2016; Bukhman et al., 2015).

These three interlocked challenges—the sheer disparity between NCDs / infectious diseases’ resources and burden, the negligible growth in resource commitments despite NCDs’ expanded profile on the international stage, and the dynamic scientific and political contest of NCDs’ social construction and framing—create an interesting empirical puzzle that has important implications for the politics and governance of global health. What is blocking the political progress in expanding resources and academic focus on a progressive strategy for NCD care and control?

One hypothesis—that is supported by the findings of this paper—is that the dominant NCD framing (especially from the WHO and the global scientific community) historically has been rooted in a North American / European-centric view: a narrow set of illnesses and their associated individual-level, modifiable, statistically determined risk factors as the root causes (4×4 Framework). This framing has blocked the political momentum of NCDs because 1) it situates the locus of cause in bad decisions/behaviors of individuals and 2) it appears to be an unhappy byproduct of economic development and income growth. This framing renders the true experience of the poorest and most marginalized invisible to global policy makers and makes it difficult for activists to demand new modes of financing to support ministries of health to build progressive NCD treatment and prevention programs.

Works Cited

Airhihenbuwa, C. O., Ford, C. L., & Iwelunmor, J. I. (2014). Why culture matters in health interventions: lessons from HIV/AIDS stigma and NCDs. Health Educ Behav, 41(1), 78–84. http://doi.org/10.1177/1090198113487199\r1090198113487199 [pii]

Babchuk, N., Keith, B., & Peters, G. (1999). Collaboration in sociology and other scientific disciplines: A comparative trend analysis of scholarship in the social, physical, and mathematical sciences. The American Sociologist, 30(3), 5–21. http://doi.org/10.1007/s12108-999-1007-5

Binagwaho, A., Muhimpundu, M. A., & Bukhman, G. (2014). 80 under 40 by 2020: an equity agenda for NCDs and injuries. The Lancet, 383(9911), 3–4. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62423-X

Beaglehole, R., & Bonita, R. (2010). What is global health? Global Health Action, 3(0), 1–2. http://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v3i0.5142

Brown, P. (1995). Naming and Framing: The Social Construction of Diagnosis and Illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 34–52.

Bukhman, G., Mocumbi, A. O., & Horton, R. (2015). Reframing NCDs and injuries for the poorest billion: a Lancet Commission. The Lancet, 386(10000), 1221–1222. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00278-0

Bukhman, G., Bavuma, C., Gishoma, C., Gupta, N., Kwan, G. F., Laing, R., & Beran, D. (2015). Endemic diabetes in the world’s poorest people. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 3(6), 402–403. http://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00138-2

Cappell, C. L., & Guterbock, T. M. (1992). Visible Colleges: The Social and Conceptual Structure of Sociology Specialties. American Sociological Review, 57(2), 266–273.

Conrad, P., & Barker, K. K. (2010). The social construction of illness: key insights and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(S), S67–S79. http://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510383495

Daipha, P. (2001). The intellectual and social organization of ASA 1990–1997: Exploring the interface between the discipline of sociology and its practitioners. The American Sociologist, 32(3), 73–90. http://doi.org/10.1007/s12108-001-1029-0

Daniels, M. E., Donilon, T. E., & Bollyky, T. J. (2014). The Emerging Global Health Crisis: Noncommunicable Diseases in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. New York.

Fassin, D. (2012). That Obscure Object of Global Health. In Medical Anthropology at the Intersections: Histories, Activisms, and Futures, (p. 352).

Geneau, R., Stuckler, D., Stachenko, S., McKee, M., Ebrahim, S., Basu, S., …Beaglehole, R. (2010). Raising the priority of preventing chronic diseases: a political process. The Lancet, 376(9753), 1689–1698. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61414-6

Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases, 2013-2020. Rep. World Health Organization, 2013. Web. <http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/94384/1/9789241506236_eng.pdf>.

Gondal, N. (2011). The local and global structure of knowledge production in an emergent research field: An exponential random graph analysis. Social Networks, 33(1), 20–30. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2010.09.001

Goyal, S., Van Der Leij, M. J., & Moraga‐González, J. L. (2006). Economics : An Emerging Small World. The University of Chicago Press, 114(2), 403–412.

Hill, V., & Carley, K. M. (1999). An approach to identifying consensus in a subfield: The case of organizational culture. Poetics, 27(1), 1–30. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-422X(99)00004-2

Kaplan, N. (1965). The norms of citation behavior: Prolegomena to the footnote. American Documentation, 16(3), 179–184. http://doi.org/10.1002/asi.5090160305

Katz, A. R. (2013). Noncommunicable diseases: Global health priority or market opportunity? An illustration of the World Health Organization at its worst and at its best. International Journal of Health Services, 43(3), 437–458. http://doi.org/10.2190/HS.43.3.d

Keane, C. (1998). Globality and Constructions of World Health. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 12(2), 226–240.

Kessler, M. M. (1963). Bibliographic coupling between scientific papers. American Documentation, 14(1), 10–25. http://doi.org/10.1002/asi.5090140103

Kwan, G. F., Mayosi, B. M., Mocumbi, A. O., Miranda, J. J., Ezzati, M., Jain, Y., Bukhman, G. (2016). Global Burden of Cardiovascular Disease Endemic Cardiovascular Diseases of the Poorest Billion. http://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.008731

Lantz, P. M., & Booth, K. M. (1998). The social construction of the breast cancer epidemic. Social Science and Medicine, 46(7), 907–918. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00218-9

Lievrouw, L., Rogers, E.M., Lowe, C.U., Nadel, E., 1987. Triangulation as research strategy for identifying invisible colleges among biomedical scientists. Social Networks 9 (3), 217–248.

Mamudu, H. M., Yang, J. S., & Novotny, T. E. (2011). UN resolution on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases: an opportunity for global action. Global Public Health, 6(4), 347–353. http://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2011.574230

Moody, J., & Light, R. (2006). A view from above: The evolving sociological landscape. American Sociologist, 37(2), 67–86. http://doi.org/10.1007/s12108-006-1006-8

Newman, M. E. J. The mathematics of networks. http://www-personal.umich.edu/~mejn/papers/palgrave.pdf. Center for the Study of Complex Systems, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI

Small, H., & Griffith, B. C. (1974). The Structure of Scientific Literatures I : Identifying and Graphing Specialties Author ( s ): Henry Small and Belver C . Griffith Published by : Sage Publications , Ltd . Stable URL : http://www.jstor.org/stable/284536 REFERENCES Linked references are av. Science Studies, 4(1), 17–40.

Šubelj, L., Fiala, D., & Bajec, M. (2014). Network-based statistical comparison of citation topology of bibliographic databases. Scientific Reports, 4, 6496. http://doi.org/10.1038/srep06496

Wang, P., Sharpe, K., Robins, G. L., & Pattison, P. E. (2009). Exponential random graph (p *) models for affiliation networks. Social Networks, 31(1), 12–25. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2008.08.002

Wasserman, Stanley; Faust, Katherine (1994). Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications (Structural Analysis in the Social Sciences) (p. 188). Cambridge University Press. Kindle Edition.

Whyte, S. R. (2012). Chronicity and control: framing “noncommunicable diseases” in Africa. Anthropology & Medicine, 19(1), 63–74. http://doi.org/10.1080/13648470.2012.660465

Sanyu Mojola’s “Love, Money, and HIV: Becoming a Modern African Woman in the Age of AIDS” (2014) presents a compelling, multilayered, processual account of the ways that changing ideas of modernity and the expansion of a gendered market economy combines with the physiological and ecological structure of HIV transmission risk to produce the outrageous inequity in HIV burden borne by women in Africa. She says, “Specifically, I illustrate how consuming young women have been cultivated and produced, in three contexts—communities, schools, and labor markets” (p. 8). For her, the dramatically gendered disparities in HIV burden and experiences can only be adequately explored by tracing the interwoven threads of the structuring market, its shaping force on cultural norms and dispositions, and the implications for young womens’ search for love and desire amidst the specter of HIV. As Mojola describes, women are caught between the culturally and institutionally cultivated demand to consume—products, beauty goods, daily signs of status and modernity—while also being structurally excluded from the vast majority of the formal labor market and consistent income potential. The demand for stable income leads to emergence of various forms of “transactional sexual relationships” that take on different forms in different settings, but all help to satisfy consumptive needs and norms.

Sanyu Mojola’s “Love, Money, and HIV: Becoming a Modern African Woman in the Age of AIDS” (2014) presents a compelling, multilayered, processual account of the ways that changing ideas of modernity and the expansion of a gendered market economy combines with the physiological and ecological structure of HIV transmission risk to produce the outrageous inequity in HIV burden borne by women in Africa. She says, “Specifically, I illustrate how consuming young women have been cultivated and produced, in three contexts—communities, schools, and labor markets” (p. 8). For her, the dramatically gendered disparities in HIV burden and experiences can only be adequately explored by tracing the interwoven threads of the structuring market, its shaping force on cultural norms and dispositions, and the implications for young womens’ search for love and desire amidst the specter of HIV. As Mojola describes, women are caught between the culturally and institutionally cultivated demand to consume—products, beauty goods, daily signs of status and modernity—while also being structurally excluded from the vast majority of the formal labor market and consistent income potential. The demand for stable income leads to emergence of various forms of “transactional sexual relationships” that take on different forms in different settings, but all help to satisfy consumptive needs and norms.